Who’s who in the Franklin expedition

Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site

In 1845, the Franklin Expedition -- two British Navy ships, with 129 crewmembers -- sailed into the Arctic, and disappeared. Many expeditions set out to find the missing ships and men. Inuit played an integral part in solving the enduring mystery.

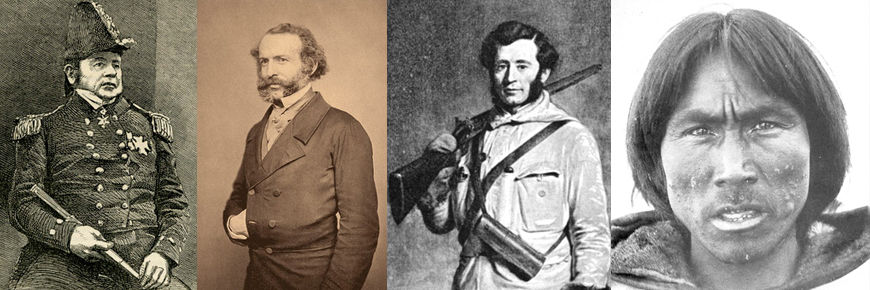

Franklin and the crew

Sir John Franklin

Date of birth: April 16, 1786 Date of death: June 11, 1847

The British Admiralty – the administrative arm of the Royal Navy – appointed Sir John Franklin to lead the 1845 Arctic expedition. Franklin, a career naval officer, had not been to the Arctic for almost 20 years. In 1818, he had served as captain on HMS Trent during an expedition instructed to sail across the North Pole; and between 1819 and 1829, he had led two overland expeditions to explore and chart the northern coast of Canada’s mainland.

During his early naval career, Franklin had served on ships that participated in the Napoleonic Wars – including the Battle of Trafalgar – and the charting of Australia’s coastline. He later captained a vessel that patrolled the Mediterranean Sea, and from 1837 to 1843, served as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land (today Tasmania, Australia).

Early life and career

John Franklin was born in 1786 in Spilsby, England, to a middle-class merchant family. Despite the opposition of his father, who hoped he would become a clergyman, Franklin joined the Royal Navy at age 14. Like many sailors of this era, he served in many capacities, rising in the ranks and gaining experience. He served on ships during the Napoleonic Wars, including during the Battle of Copenhagen (1801) and the Battle of Trafalgar (1805). He was wounded during the War of 1812 in North America. His first voyage of discovery (1801-1803) charted the Australian coast, an experience that probably began Franklin’s interest in exploration. Once Napoleon was finally defeated and peace arrived, Franklin, like many members of the British military, was discharged and found himself on half pay and without work. The British Admiralty made use of some of these available ships and men in a government-sponsored revived search for a northwest passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Franklin participated in one of these first expeditions. In 1818, he captained HMS Trent, a small whaling vessel in an expedition led by Captain Buchan on Dorothea. Believing the North Pole was in open water, the expedition planned to sail from Spitsbergen (north of Norway) to the Bering Strait. Impenetrable pack ice forced them back.

Overland survey for the Northwest Passage

In 1819, the Admiralty put Franklin in command of an overland expedition to chart the northern coast of North America. The expedition was part of a broader plan to find a passage by determining the limits of the continent. These overland explorations were accompanied by ongoing sea voyages to chart the Arctic Archipelago and locate a sea passage.

While Franklin and his men managed to survey the coast from the mouth of the Coppermine River, the expedition suffered from the outset. Fur trade companies had been asked to provide supplies and guides, but their support was insufficient. Franklin and his men lacked the experience and skills to survive on the land. In the end, the men were reduced to eating deer skins, bones, lichen, and boiled boot leather before George Back and a party of Dene finally arrived with food. By that time, starvation, exposure, and in-fighting had killed 11 of the 19 men.

The disastrous expedition became infamous: back in London, Franklin was known as "the man who ate his boots." During his time at home, he married Eleanor Anne Porden and their daughter Eleanor Isabella was born. The marriage was short-lived: Eleanor had suffered from ill health for years and died of tuberculosis while Franklin was en route to his second Arctic survey.

A more successful survey

The Admiralty appointed Franklin to lead a second overland expedition (1825-1827) to explore more of the Arctic coast. Learning from the mistakes of his last expedition, he planned a more self-sufficient effort. He made preparations well in advance and sent supplies ahead to Hudson's Bay Company posts.

Franklin charted nearly 2,000 kilometres of coastline from the mouth of the Mackenzie River. Passing through Upper Canada on his return journey in August 1827, Franklin stopped at a small lumber community called Bytown, which later became Ottawa, Canada's capital. While there, he laid a stone for one of the entrance locks of the Rideau Canal.

Rising up and a final voyage

In November 1828, he married Jane Griffin, a friend of his late wife. King George IV knighted him in 1829. Although Franklin anticipated further Arctic expeditions, the Admiralty sent him to patrol the Mediterranean Sea during the Greek War of Independence from 1830-33. In 1836, Franklin accepted the appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania).

Shortly after returning to London in 1843, Franklin learned of the government’s plans to renew the search for the Northwest Passage. At the age of 58, he was made commander of the expedition, which left Great Britain on May 19, 1845. In a few precious letters sent home before the ships entered the Arctic, officers on board HMS Erebus describe Franklin as strongly religious, well liked and interesting, often recounting his earlier explorations over shared dinners in his cabin.

Sir John Franklin died on June 11, 1847, according to the “Victory Point note” signed by Francis Crozier and James Fitzjames.

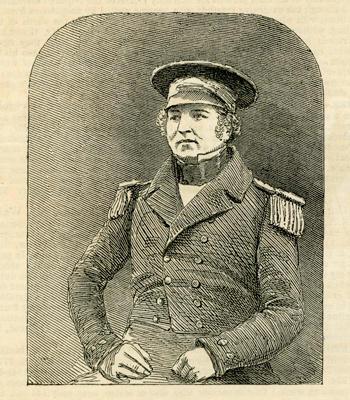

Captain Francis Crozier

Date of birth: September, 1796 Date of death: Not recorded

When Francis Crozier was appointed second in command of the Franklin Expedition, he had already captained HMS Terror in a four-year Antarctic mission. He had extensive experience of both northern and southern polar waters. He was a scientist as well as a sailor, developing an expertise in terrestrial magnetism that earned him a fellowship in the Royal Society.

After Franklin’s death in June 1847, responsibility for the expedition fell to Crozier. Crozier would have been responsible for the decision to abandon the ships and to lead the men on an overland journey south. Inuit observed their progress. Some of their stories survive through Inuit oral traditions.

Early life and career

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier was born to an affluent Irish family in Banbridge, Northern Ireland in 1796. He began his naval career at age 13.

By the time Crozier joined the Franklin Expedition, he had already participated in several polar explorations, including two attempts to navigate the Northwest Passage, a voyage to reach the North Pole, and a journey to explore Antarctica.

Crozier’s first venture to the Arctic

Crozier was part of William Edward Parry’s 1821 effort to find the Northwest Passage. Parry was one of the most successful Arctic explorers of the era, and refined many of the Royal Navy techniques for travelling in the Arctic and surviving long, cold, dark winters. Crozier made scientific observations during the voyage, and befriended fellow midshipman James Clark Ross. Their ships, HMS Fury and HMS Hecla, spent two winters in the region, returning home in 1823. During their first winter, they encountered a group of Inuit near Southampton Island, who informed the explorers that there was no navigable route through Hudson Bay leading to a passage. The expedition returned to Britain with greater geographical understanding of the Arctic.

Re-joining the search for the Northwest Passage

Crozier joined Parry again in 1824 with Hecla and Fury. This expedition ended in disaster when, in August 1825, HMS Fury was severely damaged by ice and abandoned off the eastern coast of Somerset Island. The other expedition ship, HMS Hecla, carried both crews to Peterhead, Scotland. Crozier was promoted to lieutenant for his excellent service and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society for his scientific work.

In April 1827, both Crozier and Ross re-joined Parry in his last Arctic expedition, an unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole. While Parry and Ross led small overland parties from the northern tip of present-day Norway, Crozier was given command of the ships. The expedition returned home in August.

Geographical research of Antarctica

In 1839, the Royal Society and British Academy persuaded the British government to launch an Antarctic expedition for scientific and geographical research. On September 30, 1839, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus set sail with Crozier as captain of HMS Terror; while overall leadership fell to his friend Ross. They spent several months at Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land (now known as Tasmania), where Lieutenant-Governor Sir John Franklin warmly welcomed them.

The names of Antarctic geographic features reflect their four-year mission: Mount Erebus, Mount Terror, Ross Ice Shelf, and Cape Crozier. They raised the British flag at the South Magnetic Pole, a remarkable accomplishment for Ross—he had located the North Magnetic Pole on the west coast of Boothia Peninsula in 1831.

The last voyage

Crozier was once again appointed captain of HMS Terror with Franklin’s 1845 expedition. Scientific survey was an important part of the expedition although it would not be Crozier’s responsibility. The Admiralty assigned this task to Commander James Fitzjames of HMS Erebus.

Upon Franklin’s death in June 1847, Crozier assumed command of the expedition. With James Fitzjames, he co-signed the “Victory Point note” in April 1848, which reported Franklin’s death, and the decision to abandon the ships and lead the men south to the Back River.

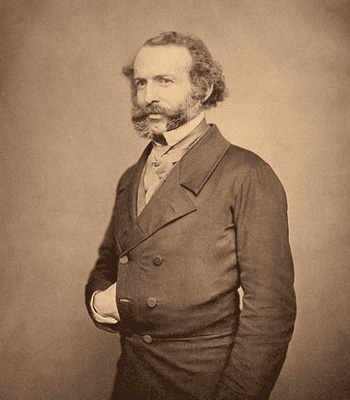

Captain James Fitzjames

Date of birth: July 27, 1813 Date of death: Not recorded

James Fitzjames was third in command of the Franklin Expedition and commander of HMS Erebus. Prior to this, he had seen naval action in Syria, Egypt, and China, but had not sailed on any polar expedition. He was in charge of recruiting officers and crew prior to the expedition.

During the voyage, Fitzjames was responsible for magnetic research. Following Franklin’s death and before setting out overland with their surviving men, he and Crozier co-signed the note left in the Victory Point cairn.

129 men lost at sea

In the 19th century, the spelling of names was not consistent. The spelling of the crews’ names used here are the ones contained in the original 1845 Muster books produced by the Royal Navy from the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich UK.

HMS Erebus crew (in alphabetical order)

HMS Terror crew (in alphabetical order)

Early searchers looking for the missing expedition

Over 30 Arctic expeditions participated in the official search effort between 1848 and 1854; 12 major expeditions were sent in 1850 alone. The early searchers found in this section represent only a small number of people who searched for the missing ships.

Lady Jane Franklin

Date of birth: December 4, 1791 Date of death: July 18, 1875

Jane Franklin was relentless. She played a significant role in the search for her husband, pressuring the Admiralty when their interest waned. Over the course of many years, she wrote numerous letters to government leaders and to the press. She financed various expeditions herself. When the British government was unwilling to fund further searches, Lady Franklin organized and spent almost £8,000 of her own money toward the total cost of over £10,000 (around $2 million today) to finance the McClintock expedition to King William Island.

Early life

Jane Griffin married John Franklin in 1828. Well-educated and resourceful, Lady Franklin travelled extensively with her husband. She had been intensely interested in exploration for many years and had followed the travels of many of the Arctic explorers, including Edward Parry’s sea voyage and John Franklin’s first overland expedition that both departed in 1818. During her husband’s appointment as lieutenant-governor in Van Diemen’s Land (today Tasmania), she developed a keen interest in his professional life. They returned to London in 1843. Two years later, Franklin left on his search for the Northwest Passage. It would be the last she would see of him.

The search for Sir John Franklin

In 1848, the British Parliament offered an initial £10,000 reward for the rescue of Franklin, to which Lady Franklin eventually added £3,000 of her own money (over $500,000 today). Lady Franklin appealed to Sir John Richardson to accompany him on an Admiralty-sponsored overland expedition in search of the missing men. Richardson, a friend of Franklin’s, was another experienced Arctic explorer and had participated in Franklin’s second overland expedition. Once she realized that, as a woman, she would be barred from accompanying search expeditions, she used every means at her disposal to further the quest for her missing husband. She wrote countless letters and published numerous articles to raise public awareness, and succeeded in mobilizing resources for the search.

Public sympathy

A sympathetic press painted Lady Franklin as a tragic heroine. Her tireless dedication to the search prompted The Quebec Mercury to write:

"[…] we shall not be astonished if this noble woman should cross the snowy regions of the North, […] and on the shores of the Arctic sea, peril her life in searching to rescue him [...]

When Lady Franklin called for a day of prayer in honour of her husband, more than 60 churches obliged. Popular songs and poems celebrated her devotion to her lost husband. More than any other single person, Lady Franklin elevated a remote naval search into a crusade.

Funding search expeditions

Lady Franklin not only funded large portions of her own searches independent of government efforts, she found new sympathizers such as Henry Grinnell, an American businessman who financed two expeditions. She convinced United States President Zachary Taylor to contribute support from the American Navy. She also persuaded the Tsar of Russia to send a search expedition to the Bering Strait. Supported by the public, Lady Franklin pressured the government to intensify the search. In 1849, the Admiralty increased the reward for finding Franklin to £20,000 (more than $2 million today).

Over the years, Lady Franklin financed and organized seven expeditions. Such operations were very expensive, but she publically declared that she would exhaust her entire fortune if necessary. Her determination led to serious rifts within the Franklin family and poisoned her relationship with Eleanor, Franklin’s daughter from his first marriage. In 1851, Lady Franklin’s own father disinherited her.

Commemorating Sir John Franklin

In the fall of 1854, John Rae returned from the Arctic with sobering and shocking news: Inuit stories of ill and starving white men resorting to cannibalism. Many Inuit had acquired relics from these men, items that were from the missing expedition. Lady Franklin vigorously defended her husband’s honour. At her bidding, Charles Dickens discredited Rae and his Inuit informants in his weekly journal, Household Words.

When the McClintock expedition confirmed Franklin’s death, Lady Franklin turned her attention to cementing his legacy. She financed two memorials to Franklin and his final expedition, one in Waterloo Place, London, and the other in Hobart, Tasmania. Her campaign to have a bust of her husband installed in Westminster Abbey was realized two days after her own death in July 1875.

John Rae

Date of birth: September 30, 1813 Date of death: July 22, 1893

John Rae, a Hudson’s Bay Company surgeon and surveyor, was the first explorer to provide any clear information on the fate of Franklin’s crew. In comparison to many of the mid-19th century Arctic explorers, Rae developed many of his impressive skills from Indigenous hunting and travelling techniques. While travelling towards Boothia Peninsula in 1854, Rae heard stories from local Inuit about white men to the west, who were sick and starving or dead. Eventually, Captain McClintock confirmed that these were indeed about the men from HMS Erebus and HMS Terror travelling along King William Island.

Early life and career

Born in 1813 in the Orkney Islands, Rae studied medicine in Edinburgh and became a practicing surgeon at the age of 19. He joined the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1834, and was sent to Moose Factory (Ontario) on supply ship, Prince of Wales. When the vessel became stranded by pack ice at Charlton Island in James Bay, many of the men suffered from scurvy. A resourceful Rae treated them by using cranberries and sprouts of wild pea he found under the snow.

From surgeon to surveyor

During his time at Moose Factory, Rae adopted many of the Cree methods of hunting and travelling. In 1845, Rae set out to map Canada’s northern continental coastline. He assembled an experienced group of Scotsmen, an Englishmen, French Canadians, Cree and Métis. Two Inuit hunters joined them: Ouligbuck (also spelled Ooligbuck and Uligpak) and his son William Ouligbuck, Jr., or Mar-ko.

Their explorations helped define possible routes through the still-undiscovered Northwest Passage. Rae conclusively determined that Boothia was a peninsula connected to the mainland. The expedition mapped 1,050 kilometres of new coastline, connecting the charts of previous explorers.

Rae used Indigenous hunting, travel, and survival techniques. He learned to build snow houses, run dog sleds, and he wore Indigenous clothing which he found more appropriate than the European options. His teams were small and carried little equipment, making his expeditions more flexible and self-sufficient than any of his contemporaries. He was well known for his admiration of the local population, generally preferring their company.

Evidence of Franklin’s fate

In terms of solid evidence about Franklin and his crew, Rae’s fourth and final Arctic expedition was the most successful. In April 1854, Inuit of the Pelly Bay region told Rae about Kabloonas (white men) who had starved to death four years earlier – and reports of cannibalism. Rae gathered additional stories at Repulse Bay and obtained Franklin relics at both locations.

In his report to the Admiralty, he included the information regarding the crew’s reported cannibalism. Although this aspect of Rae’s report drew strong criticism, the government ultimately granted Rae a reward in July 1856, which he chose to share with his companions from 1854.

Rae’s retirement

Rae retired from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1857, but continued to travel. He conducted an 1860 survey for the Atlantic Telegraph Company across Iceland and Greenland, and in 1865, charted northern British Columbia for the Canadian Telegraph Company. He also published several works about his travels and lectured extensively. Although John Rae was never knighted, today he is recognized as one of the great Arctic explorers of the 19th century.

Francis Leopold McClintock

Date of birth: July 8, 1819 Date of death: November 17, 1907

Francis McClintock, an experienced naval officer, first went to the Arctic as part of the Royal Navy’s initial 1848 search for HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. After John Rae’s report about Inuit seeing sick and starving men, Lady Franklin engaged McClintock to command the steam yacht, Fox. McClintock’s expedition embarked in July 1857, intending to rescue survivors and recover any written records. In 1859, he and his men explored King William Island, recovering relics from the expedition and recording some Inuit accounts. But his second in command, Lieutenant Hobson, made the most startling discovery: an actual written note from Franklin’s crew.

Early life and career

Born in Ireland in 1819, Francis Leopold McClintock joined the Royal Navy at the age of 12. He served in various postings in the Arctic, eventually rising through the ranks to lieutenant in 1845.

The 1848 search for Franklin

McClintock served as second lieutenant with James Clark Ross in 1848, in one of the first expeditions sent in search of Franklin. When Ross’s ships HMS Enterprise and HMS Investigator became trapped by ice on the northern coast of Somerset Island, the expedition travelled overland but found no trace of Franklin. The west coast of Somerset Island near Bellot Strait was packed with ice, and Ross was convinced no ship could have navigated these waters. He was unaware that just a few months earlier, in April 1848, Franklin’s second in command, Francis Crozier, had abandoned his ships less than 300 kilometres to the south.

Continued search for the Franklin Expedition

In 1850, McClintock was first lieutenant aboard HMS Assistance during another search expedition. He was next appointed captain of HMS Intrepid, part of Sir Edward Belcher’s expedition (1852-54), the last of the large Royal Navy search efforts.

During this era, Royal Naval expeditions travelled overland and on sea ice with large sledges hauled by teams of men. McClintock refined sledge designs and techniques, even making recommendations for provisions and other equipment. In the spring of 1853, McClintock led the longest man-hauled sledge trip ever undertaken in the North American Arctic. In 105 days, he travelled 2,250 kilometres and mapped previously uncharted parts of Prince Patrick, Emerald, Eglinton, and Melville islands. The Belcher Expedition is known, in part, for the rescue of the crew of HMS Investigator trapped on Banks Island. The return trip home was slow. Ice beset Belcher’s ships during the winter of 1853-54 and, when it appeared that they might be trapped for another winter, Belcher ordered the abandonment of four of the five ships, including HMS Intrepid. The expedition arrived back in Great Britain in October 1854.

The Fox

When Lady Franklin determined that she would follow up on Rae’s information about the fate of Franklin’s men, she purchased the yacht Fox and had it refit for Arctic service. McClintock accepted the position as commander of this new expedition, which set sail in July 1857. Fox had a small complement of 25 officers and crew, insufficient for man-hauled sledges. While at Disko Bay, Greenland, McClintock acquired sled-dogs and hired an Inuit driver. The ship spent the winter beset in the ice in Baffin Bay and did not enter Lancaster Sound until spring 1858, eventually reaching Bellot Strait and spending the second winter (1858-59) at its eastern end.

McClintock encountered a group of Inuit at Cape Victoria on Boothia Peninsula who had a variety of silverware and other relics from Franklin’s crew. The Inuit reported that one ship had been crushed by ice to the west of King William Island.

In April 1859, McClintock and his junior officer, Lieutenant William Hobson, travelled to King William Island, where they separated. McClintock travelled east, where he recovered silverware and wooden items from HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. He also examined a heavy sledge carrying a ship’s boat, and most tellingly, skeletons, graves, and abandoned books and clothing.

One document, two messages

Meanwhile, Hobson had found a stone cairn on Victory Point, near the island’s northern tip. Inside was a metal tube containing a note, on which were written two messages. The first confirmed the Franklin Expedition had overwintered at Beechey Island after later becoming ice-bound in September 1846 north of King William Island. The second message, added in April 1848, reported that a total of 24 officers and men had died, including Sir John Franklin (on June 11, 1847). The 105 survivors had abandoned ship and were striking out overland to the Great Fish (Back) River.

The expedition returned to England in September. McClintock received a knighthood, was granted “freedom of the City of London”, and elected a Fellow of both the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society. His last visit to the Arctic was in 1860 as captain of HMS Bulldog, part of a survey for a trans-Atlantic telegraph cable. He was promoted to admiral the day before his retirement in 1884.

Charles Francis Hall

Date of birth: circa. 1821 Date of death: November 8, 1871

American journalist Charles Hall was certain some of Franklin’s men must have survived. He spent over a decade interviewing Inuit with the help of translators and guides Taqulittuq and Ipiivik. One encounter with Inuk Inukpujijuq provided a firsthand account of visiting a ship and provided the general location of a shipwreck. Hall’s reports and interviews formed an invaluable record: other searches mined his information, including Parks Canada’s multi-year search that began in 2008.

Frederick Schwatka

Date of birth: September 29, 1849 Date of death: November 2, 1892

The search for Franklin inspired people beyond Britain and Canada. Frederick Schwatka, an American who had served in the U.S. Army, believed that documents from the Franklin expedition would have survived and could still be found. Although he had never been to the Arctic, he was appointed as leader of a privately-funded expedition sponsored by the American Geographical Society of New York. He departed from New York in June 1878 with a small party of explorers. Between 1879 and 1880, Schwatka undertook a 5,232-kilometre dog sled journey, the longest on record at the time. While Schwatka did not find any new written documents, he collected many relics and recorded Inuit histories. Ipiivik, who had previously worked for Hall, was Schwatka’s guide and translator.

Inuit searchers

Early searchers looking for the missing expedition encountered Inuit who had either witnessed the terrible and tragic end of Franklin’s men firsthand, or learned of it through oral histories passed down through generations. These invaluable accounts, recorded in the nineteenth century, as well as present day Inuit knowledge, contributed to the ships being found in 2014 and 2016. Meet some of the Inuit who took part in early searches and who importantly served as interpreters, guides, and expedition team members.

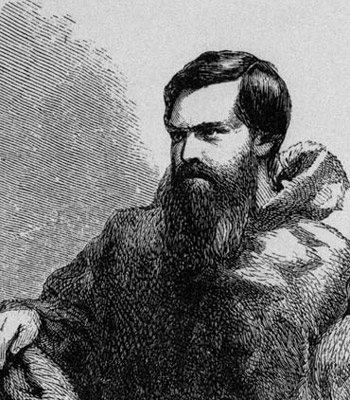

William Uligpak

Date of birth: Not recorded Date of death: Not recorded

William Uligpak (William Ouligbuck Jr), also known as Mar-ko, was an Inuit hunter who served as translator and guide for Arctic explorer John Rae. Mar-ko’s father had also participated in Rae’s early expeditions and travelled with other European explorers including on John Franklin’s 1825-27 overland expedition. In 1854, it was Mar-ko’s conversations with people of the Pelly Bay region that provided Rae with the first evidence of the fate of the men from HMS Erebus and Terror, including accounts of cannibalism. With Mar-ko’s assistance, Rae recovered a number of objects from the Franklin expedition. When the accuracy of Mar-ko’s information was challenged in London, Rae defended his translator, as well as the character of their Inuit informants.

Taqulittuq and Ipiivik

Date of birth: Late 1830s Date of death: Taqulittuq died on December 31, 1876 and Ipiivik died circa 1881

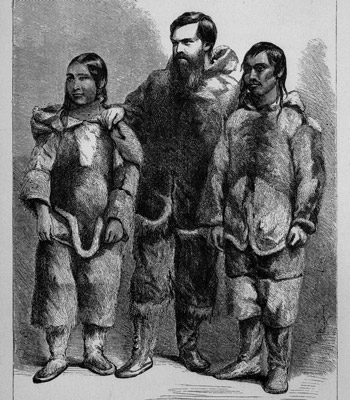

Husband and wife team Taqulittuq and Ipiivik supported Charles Hall in his search for survivors from the Franklin expedition. Taqulittuq and Ipiivik came from the Baffin Island area and had learned English from whalers, eventually travelling to England to further their study. They were also known by English names Hannah and Joe. Hannah served as a translator, while Joe primarily worked as a hunter and guide.

Early life

Wife and husband Taqulittuq and Ipiivik were born near Cumberland Sound on Baffin Island, likely in the late 1830s. Their names have had several spellings including Tookoolito and Ebierbing. After meeting a British whaling captain, they agreed to travel to Great Britain where they spent 1853 to 1855 learning English. During this time they were presented to Queen Victoria.

Travelling with Charles Hall

They met American explorer Charles Francis Hall in 1860 on Baffin Island. Hall, an American journalist who had become fascinated with the Arctic, was determined to find survivors of the Franklin expedition. Taqulittuq and Ipiivik accompanied Hall on two Arctic expeditions from 1860-62 and another from 1864-69. After Hall’s death in 1871, the couple participated in a third expedition in search of the North Pole between 1871 and 1873.

Taqulittuq was a seamstress and interpreter while Ipiivik usually acted as a hunter and guide. With their help, Hall questioned groups of Inuit and obtained information as to the possible locations of Franklin’s ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror.

Taqulittuq and Ipiivik were also instrumental in helping Hall raise funds for his expeditions, travelling to the United States where they appeared in presentations wearing traditional Inuit clothing and answered questions from the audience about their way of life.

Ice floe survival

Hall died at the beginning of his third journey, known as the Polaris expedition. In October 1872 a violent storm resulted in part of the group, including Taqulittuq and Ipiivik becoming stranded on an ice floe. For over six months, this group of 19 (including 5 children) drifted almost 3,000 kilometres south from Greenland, until they were picked up by a sealing ship off the coast of Labrador. Their ordeal had lasted 196 days and has become one of the epic stories of Arctic survival. In particular, Ipiivik’s hunting and fishing skills were crucial to the entire group’s survival.

A life in the south and a return to the north

Following this expedition, Taqulittuq and Ipiivik settled in Groton, Connecticut on land they purchased with money provided by Hall. In 1875, Ipiivik joined the Pandora Expedition, an unsuccessful attempt to sail through the Northwest Passage financed by Lady Franklin.

Ipiivik returned to Groton afterwards, and Taqulittuq died from tuberculosis on December 31, 1876. In 1878, Ipiivik joined one last Arctic expedition under the command of Frederick Schwatka. Ipiivik remained in the Arctic and died around 1881. In 1981, the Canadian government jointly declared Ipiivik and Taqulittuq a National Historic Person, a designation recognizing individuals and groups of national significance.

Related links

- Date modified :