Fisgard Lighthouse, first lighthouse on the west coast of Canada

Fort Rodd Hill and Fisgard Lighthouse National Historic Sites

Safety and supremacy

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Fisgard Lighthouse was a ‘life saver’ for the many local and foreign cargo and passenger ships that travelled the unforgiving seas of the Juan de Fuca Straight—especially on foggy or stormy nights! The lighthouse was also what allowed the Royal Navy to operate at nighttime safely from Esquimalt Harbour, getting their ships in and out without running up onto the rocks.

Additionally, it was really an expression of British sovereignty. Only a couple of years before the lighthouse was built in 1860, there was a huge influx of American miners into both the Victoria area and the Fraser Valley for the Fraser Valley gold rush. Given that as recently as 1844, American politicians were campaigning to extend their territorial control as far as parallel 54°40′ north (past Prince Rupert!), this influx was alarming as it threatened to upset Britain’s dominance of the region’s. Putting this British lighthouse here underlined the fact that this was British territory and they were not going to permit it to be annexed to the United State of America.

Keepers of the light

Between 1860 and 1928, 12 people (including one woman) served as keepers at Fisgard Lighthouse:

- George Davies, 1860–1861

- John Watson, 1861

- W.H. Bevis, 1861–1879 (Died on station, 1879)

- Amelia Bevis, 1879–1880

- Henry Cogan, 1880–1884

- Joseph Dare, 1884–1898 (Drowned in Esquimalt harbour, 1898)

- W. Cormack, 1898

- John Davies, 1898

- Douglas MacKenzie, 1898–1900

- Andrew Deacon, 1900–1901

- George Johnson, 1901–1909

- Josiah Gosse, 1909–1928

A stipulation of the agreement to build the lighthouse was that its first keeper should be brought out from England, and had experience in light keeping, maintenance and repair. This “gentleman” would also be able to train other lighthouse keepers.

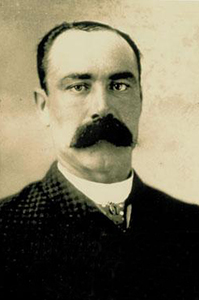

George Davies, the first lighthouse keeper, arrived from England with his wife, two children and an assistant in August 1860. He was hired for $650.00 per year, and the cost of housing (the dwelling attached to the tower), coal (for the fireplaces), and water (i.e. the cistern) was also covered by the government. He also brought along the Fresnel lens, lamp apparatus and glass-covered lantern room that would house the lamp and the lens. The colourful cast iron spiral staircase in the tower was made in sections in San Francisco.

Lighthouse keeper number three, William Bevis, stayed for 18 years. He wrote numerous letters to the government, as the house became progressively more and more uncomfortable during his tenure. The house, once built, was not properly maintained, and suffered due to its windswept, very humid and salty location. It became extremely drafty with windows and doors no longer fitting properly in their frames, and the siding on the house becoming more and more porous, so that during storms, it became as much of a chore to keep water and wind out, as it was to maintain the light.

Couples and families were encouraged to work at lighthouses, with wives taking on the chore of assistant to the lighthouse keeper. In the early days, the government paid them just over $100.00 per year, though women likely did up to 50% of the work of maintaining the light. This was much cheaper than paying a man to be the assistant keeper.

One night in 1879, William Bevis succumbed to an illness and passed away. As there was no one else capable, his wife and 16 year-old niece took over all the duties of the lighthouse keeper for nine months, until London assigned a more “suitable” person.

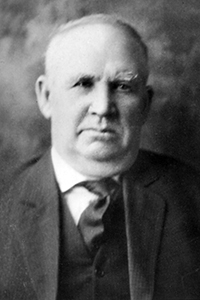

Captain Josiah Gosse was the last lighthouse keeper at Fisgard, and also the one who stayed the longest, working and living there for 19 years. He lit the lamp for the last time in 1928, the year Fisgard was automated. He stayed “on the job” for another month, just in case there was a problem.By then, it should be noted, he was only paid $360.00 per year.

As the light became less labour intensive to maintain, the salary went down, although the “benefits” of house, coal and water remained the same. The lighthouse keeper was also permitted to leave the site during the day to work elsewhere, and indeed, needed a second job in order to make ends meet.

Help shed light on the history of Fisgard's lightkeepers

Unfortunately, official correspondence reveals very little of the other lighthouse keepers’ personal lives.

Parks Canada thrives to celebrate the lives and share the stories of the people who tended the light. We are appealing to anyone who might have a connection with Fisgard (or with Race Rocks Lighthouse). If there are any old photos, letters, diaries or family stories you are willing to share, we would love to see or hear them—and so would generations of Canadians yet to come!

E-mail fort.rodd@pc.gc.ca or write to us.

Lighthouse keeper duties

Quick facts

- The light was a lamp lit at dusk; the wick needed to be trimmed every four hours

- On snowy or foggy days, the glass around the light was to be kept clear, meaning the lighthouse keeper would need to go outside in hazardous conditions

- A supply ship came in from Victoria (five miles up the coast) every 3 months. It would bring mail, food, and small supplies. Flour, sugar and meat had to be ordered in advance. Sometimes, the meat was rotten when it arrived, as it would sit on deck

- To supplement their diet, keepers were allowed to have a small garden and keep hens, although they weren’t allowed to sell the eggs

- There were no proper roads built to the adjacent Fort Rodd until the 1920’s, nor was the causeway leading to the lighthouse built until 1951. Contact between the fort and the lighthouse was minimal

- Today, the Canadian Coast Guard oversees the maintenance and proper functioning of the light. The original lens is still in place, but the lamp has been replaced with at four light bulb apparatus; should one burn out, the mechanism automatically flips a new one in place

- The automated light shines in a “one second on/one second off” sequence, and as such identifies Fisgard’s Lighthouse

Then and now

In 1860, the cost of building Fisgard was £7000.00 ($12,000 CAD). However, various government departments squabbled over who was responsible for paying. In 1956 the adjacent Fort Rodd military fortification was decommissioned, and although a caretaker was hired for the grounds, that job ended in 1957–a cost-cutting measure. This allowed vandals and whoever wanted to fully access the site without supervision. Vandalism and theft damaged the buildings and objects that remained.

Additionally in 1957, there was a fire in the lighthouse. The cause is unknown, however vandalism is suspected. The fire was spotted by the Rear Admiral from his house across the water in the naval base at CFB Esquimalt. He alerted authorities, and photographed the lighthouse on fire. The fire gutted the interior of the building with the exception of the chequered flooring. The brick exterior acted as a chimney for the fire, only that flooring plus the iron staircase survived.

Today, visitors can step inside Fisgard Ligthouse and enjoy colourful displays that tell the stories of the hardy, courageous men and women who kept the light burning. Linger in the parlour for a game of checkers, or visit a former bedroom where interactive video programs let visitors pilot a 19th-century schooner or a present-day naval patrol vessel into Esquimalt harbour. A few original boards, from the chequered flooring salvaged from the 1957 fire were installed as part of the lighthouse’s new exhibit in 2010.

Recently, exterior lighting, added to provide additional security, boosts its beauty to the delight of those participating in evening events or staying overnight in oTENTiks accommodations.

- Date modified :