Cape Breton Highlands

National Park of Canada

Management Plan, 2022

Note to readers

The health and safety of visitors, employees and all Canadians are of the utmost importance. Parks Canada is following the advice and guidance of public health experts to limit the spread of COVID 19 while allowing Canadians to experience Canada’s natural and cultural heritage.

Parks Canada acknowledges that the COVID-19 pandemic may have unforeseeable impacts on the Cape Breton Highlands National Park of Canada Management Plan. Parks Canada will inform Indigenous peoples, partners, stakeholders and the public of any such impacts through its annual implementation update on the implementation of this plan.

Table of contents

Maps

Title: Cape Breton Highlands National Park of Canada Management Plan, 2022

Organization: Parks Canada Agency

Foreword

Minister of Environment and Climate Change and Minister responsible for Parks Canada

From coast to coast to coast, national historic sites, national parks and national marine conservation areas are a source of shared pride for Canadians. They reflect Canada’s natural and cultural heritage and tell stories of who we are, including the historic and contemporary contributions of Indigenous peoples.

These cherished places are a priority for the Government of Canada. We are committed to protecting natural and cultural heritage, expanding the system of protected places, and contributing to the recovery of species at risk.

At the same time, we continue to offer new and innovative visitor and outreach programs and activities to ensure that more Canadians can experience these iconic destinations and learn about history, culture and the environment.

In collaboration with Indigenous communities and key partners, Parks Canada conserves and protects national historic sites and national parks; enables people to discover and connect with history and nature; and helps sustain the economic value of these places for local and regional communities.

This new management plan for Cape Breton Highlands National Park of Canada supports this vision.

Management plans are developed by a dedicated team at Parks Canada through extensive consultation and input from Indigenous partners, other partners and stakeholders, local communities, as well as visitors past and present. I would like to thank everyone who contributed to this plan for their commitment and spirit of cooperation.

As the Minister responsible for Parks Canada, I applaud this collaborative effort and I am pleased to approve the Cape Breton Highlands National Park of Canada Management Plan.

Recommendations

Recommended by:

Ron Hallman

President & Chief Executive Officer

Parks Canada

Andrew Campbell

Senior Vice-President, Operations Directorate

Parks Canada

A. Blair Pardy

Superintendent, Cape Breton Field Unit

Parks Canada

Executive summary

Cape Breton Highlands National Park of Canada was designated as a national park in 1936. It is located in Unama’ki, a district of Mi’kma’ki, the unceded and traditional territory of the L’nu’k, now known as the Mi’kmaq. The park protects for all time a representative example of the Maritime Acadian Highlands Natural Region, which current and future generations of Canadians and international visitors can experience and enjoy. About a five-hour drive from Halifax and a two-hour drive from Sydney, Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Highlands National Park is best known for hiking, camping and cultural experiences and offers dramatic coastal views from the world-famous Cabot Trail that encircles the park, drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

With rolling hilly plateaus, steeply cut valleys, rugged coastlines and Acadian and boreal forests, Cape Breton Highlands National Park protects, conserves and presents park ecosystems and the rich cultural heritage of inhabitants, including Mi’kmaq, Acadian and Gaelic cultures. Parks Canada works closely with neighbouring communities, some of which depend on park roadways for transportation, and the broader tourism industry, which support visitors to northern Cape Breton, including Chéticamp, Pleasant Bay, Cape North and Ingonish.

This management plan replaces the 2010 management plan. It was prepared in collaboration with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, as well as with input from local communities, tourism operators and organizations, historical and cultural groups, local and regional economic development and conservation interests, local municipalities, the province of Nova Scotia, visitors and the Canadian public at large.

Four key strategies have been outlined, which, along with associated objectives, provide strategic management direction for Cape Breton Highlands National Park over the next ten years:

Key strategy 1

A path to shared management with the Mi’kmaq

This key strategy recognizes Cape Breton Highlands National Park as a place of cultural and spiritual significance to the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia. The plan seeks to increase opportunities for the Mi’kmaq to connect with the park, have a presence in the park, practice rights-based activities in the park, and have an increased role in its shared management. Increased Mi’kmaw-led heritage interpretation programming, events, celebrations, and opportunities for economic benefit are outlined, as is working toward a shared management structure in the spirit and intent of ongoing rights implementation negotiations.

Key strategy 2

Shared conservation in the context of change

This key strategy focuses on sharing responsibilities for ecological integrity and cultural resource conservation of Cape Breton Highlands National Park. Objectives under this key strategy relate to gaining greater understanding of ecosystems and taking conservation action, in partnership with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and conservation organizations, including understanding climate change impacts and identifying adaptation options; ensuring quality habitat, particularly for species at risk; and gaining greater understanding of the cultural resources and cultural values of the park. This key strategy also emphasizes the need to ensure that Western and Mi’kmaw knowledge are seamlessly woven together, contributing to evidence-based decision-making in park management.

Key strategy 3

A destination inspired by community, nature, and culture

This key strategy focuses on the park’s role as an important local partner in sustainable tourism and as an iconic travel motivator for the region. The strategy outlines intentions for exploring non-peak season experiences, balancing sustainable visitation and meeting the expectations and abilities of park users. The strategy also broadens opportunities for local and Mi’kmaw businesses to provide services to visitors and contemplates ways to build visitation, and attract new markets, while connecting Canadians to the park through outreach and partnering initiatives.

Key strategy 4

Optimizing operations to connect Canadians with Cape Breton Highlands National Park

This key strategy focuses on improving general asset conditions and the operation of the park through partnerships with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and service providers. The key strategy outlines objectives for greening operations, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reducing water and solid waste, improving inclusion and universal accessibility, and incorporating climate change adaptation strategies.

Introduction

Parks Canada administers one of the finest and most extensive systems of protected natural and historic places in the world. The Agency’s mandate is to protect and present these places for the benefit and enjoyment of current and future generations. Future-oriented, strategic management of each national historic site, national park, national marine conservation area and heritage canal administered by Parks Canada supports the Agency’s vision:

Canada’s treasured natural and historic places will be a living legacy, connecting hearts and minds to a stronger, deeper understanding of the very essence of Canada.

The Canada National Parks Act and the Parks Canada Agency Act require Parks Canada to prepare a management plan for each national park. The Cape Breton Highlands National Park of Canada Management Plan, approved by the Minister responsible for Parks Canada and tabled in Parliament, ensures Parks Canada’s accountability to Canadians, outlining how park management will achieve measurable results in support of the Agency’s mandate.

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia are important partners in the stewardship of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, with connections to the lands and waters since time immemorial. The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, stakeholders, partners and the Canadian public were involved in the preparation of the management plan, helping to shape the future direction of the national park. The plan sets clear, strategic direction for the management and operation of Cape Breton Highlands National Park by articulating a vision, key strategies and objectives. Parks Canada will report annually on progress toward achieving the plan objectives and will review the plan every ten years or sooner if required.

This plan is not an end in and of itself. Parks Canada will maintain an open dialogue on the implementation of the management plan, to ensure that it remains relevant and meaningful. The plan will serve as the focus for ongoing engagement and, where appropriate, consultation, on the management of Cape Breton Highlands National Park in years to come.

Significance of Cape Breton Highlands National Park

Cape Breton has been inhabited by Indigenous peoples and cultures for millennia. Current day Cape Breton, or Unama’ki, has been part of Mi’kma’ki, the traditional and unceded Footnote 1 territory of the L’nu’k, now known as the Mi’kmaq.

The park was created in 1936 after much lobbying by the province of Nova Scotia for a national park, with northern Cape Breton chosen after several areas of Nova Scotia were considered. As the first national park in Atlantic Canada and the largest in the Maritimes, Cape Breton Highlands National Park protects 948 square kilometres of the Maritime Acadian Highlands Natural Region. This natural region, which is also represented by Fundy National Park in New Brunswick, is characterized by rolling hilly plateaus cut by deep valleys and cascading rivers.

The Mi’kmaq helped many waves of European immigrants to Cape Breton Island adapt to their new home. Today, cultural resources in Cape Breton Highlands National Park reflect this wide breadth of history, including Indigenous sites, and remnants of the settlements of Acadians, Scottish, Irish, French, Basque, Portuguese and others. The park also contains several recognized heritage buildings such as the Superintendent’s house, the administration building, the information bureau (now the Park Warden Office) at the Ingonish Administration Complex, and the Lone Shieling, a replica Scottish crofter’s hut.

With tourism a growing industry in the early 1900s, there was pressure on the provincial government to improve and complete a travel circuit around the northern area of Cape Breton. Constructed in the 1920s, the Cabot Trail is a world-renowned scenic highway that provides striking vistas of the coastline and the highlands. One-third of the Cabot Trail runs through Cape Breton Highlands National Park; it remains the only transportation route linking communities in northern Cape Breton.

Planning context

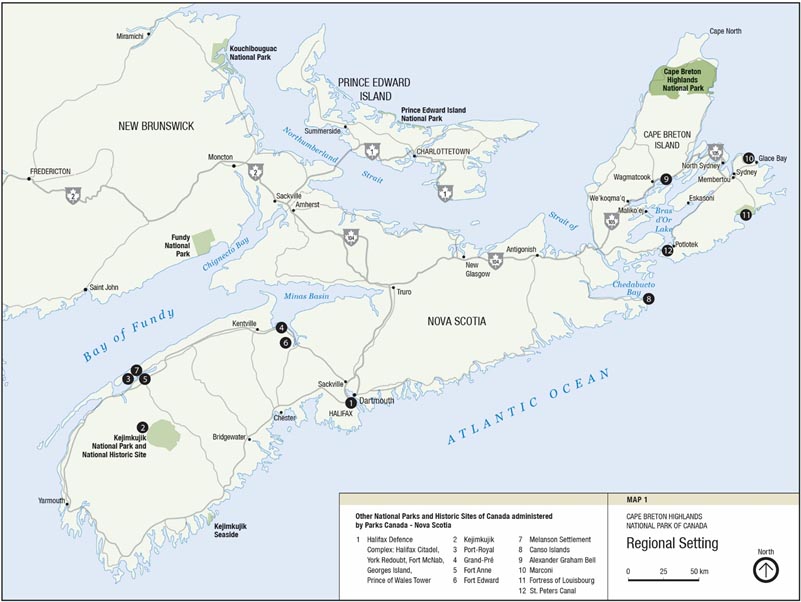

Cape Breton Highlands National Park is situated in Unama’ki, a district of Mi’kma’ki, the unceded and traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq. This area of northern Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, is about a five-hour drive from Halifax, and a two-hour drive from the closest regional centre, Sydney (Map 1). The park is often included on visitors’ Cape Breton itineraries along with national historic sites such as Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site (Baddeck) and the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site (Louisbourg). An important tourism icon and economic driver in this largely rural, resource-dependent economy, Cape Breton Highlands National Park provides employment and is an anchor for the Island’s tourism industry. Neighbouring prominent communities include: the Mi’kmaw communities of Eskasoni, Membertou, Potlotek, We’koqma’q, Wagmatcook and Maliko’ej; the predominantly Acadian community of Chéticamp, the park’s gateway community to the west; Pleasant Bay, Cape North and Neil’s Harbour to the north; and Ingonish and Ingonish Beach, the park’s gateway communities to the east.

The park is situated within the broader Cape Breton Highlands ecosystem, and is surrounded by other protected areas, including Polletts Cove - Aspy Fault Wilderness Area, Margaree River Wilderness Area, Jim Campells Barren Wilderness Area, French River Wilderness Area, Cape Smokey Provincial Park and Chéticamp Island Nature Reserve, as well as the anticipated Ingonish River Wilderness Area. Parks Canada is working with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources on landscape connectivity between the national park, the Kluskap Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area and the Bras d’Or Lake Biosphere Reserve. Park managers recognize the importance of encouraging the creation of new protected areas and enhancing landscape connectivity, including through building relationships among Indigenous, academic, and other organizations, which contributes to the ecological integrity and resiliency of Cape Breton Highlands National Park and the greater ecosystem.

Protecting a representative example of the Maritime Acadian Highlands Natural Region, the park’s dramatic landscape of verdant hills, valleys, rivers and extensive coastlines supports a variety of park ecosystems. Forest predominates, covering 69 percent of the park area, with largely boreal forest in the uplands, and Acadian forest in the lowlands. Wetlands and freshwater ecosystems are also prevalent, and the park has both eastern and western marine coastlines. The 2018 State of the Park Assessment indicated that wetlands and freshwater ecosystems were in “Good” Footnote 2 condition, and the forest ecosystem was in “Poor” but stable condition.

Cape Breton Highlands National Park is home to Acadian and boreal forest species, including 40 species of land mammals such as moose, coyote and snowshoe hare; forest and coastal bird species; and freshwater fish such as brook trout, American eel and Atlantic salmon. Several species in the park are threatened or at risk, including little brown and northern myotis bats, Bicknell’s thrush, American eel and Atlantic salmon.

Landscape-scale ecological challenges are affecting Cape Breton Highlands National Park, including climate change and over-browsing by moose. The Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources, environmental organizations and government departments, including the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources and Renewables, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, work closely with Parks Canada in the areas of joint research and monitoring.

Although the park contains cultural resources and has a long human history, including Indigenous use, more research, particularly collaborative archaeology, is needed; much more remains to be known about the cultural heritage of the park to adequately conserve and present it.

Cape Breton Highlands National Park is a significant economic driver and leader in the Island’s tourism industry. People primarily visit the park for camping, hiking and driving the Cabot Trail. Park visitation was 301,270 in 2019–2020, a total increase of about 22 percent from five years prior. Park visitors are typically first-time visitors in adult-only groups, with one-third of visitors from outside of Canada, and two-thirds of Canadian visitors coming from outside of the Atlantic region. Striking reductions in visitation were initially seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, although visitation is expected to rebound quickly as travel restrictions are lifted.

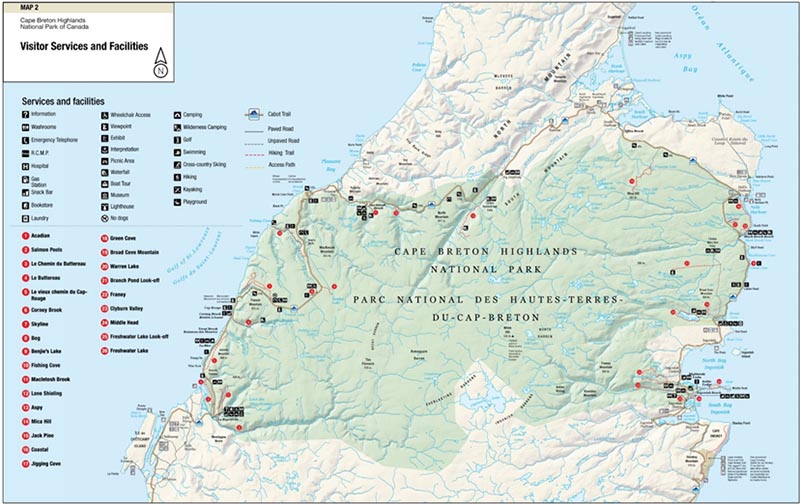

Along the Cabot Trail there are many pulls-offs with stunning views and interpretive signage, including new trilingual signage with information in Mi’kmaq, French and English. The park has two visitor centres, one in the west near Chéticamp, and one in the east in Ingonish, where the park administration complex is also located. There are six frontcountry campgrounds with a total of about 360 camping sites and 20 oTENTiks in the three largest campgrounds: Chéticamp, Broad Cove and Ingonish Beach. There is one backcountry campground, Fishing Cove, with eight campsites. In addition, the park has five day-use and/or picnic areas and about 130 kilometres of frontcountry hiking trails. While Parks Canada owns the Keltic Lodge and Highland Links golf course, these are operated by a third party under lease agreement. Between 2015 and 2019, Parks Canada invested over $120 million in infrastructure in the park, including visitor centres and facilities, day-use areas, parking lots, trails and campgrounds, as well as roadways and bridges (Map 2).

There is a growing relationship with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia at Cape Breton Highlands National Park, particularly with respect to collaborative ecosystem management and monitoring, and visitor programming. Over the past six years, the park has worked closely with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources on resource management issues of mutual interest, including moose management, forest management and use, and the management of aquatic ecosystems. The Parks Canada—Mi’kmaq Unama’ki Advisory Committee, a structure established under an interim arrangement with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, provides guidance on management direction on matters of interest to the Mi’kmaq. The Unama’ki Advisory Committee includes representation from the Mi’kmaw communities of Membertou, Wagmatcook, We’koqma’q, Potlotek, Eskasoni and Paqtnkek. Established in 2012 and renewed again in 2017, the interim arrangement describes the relationship between Parks Canada and the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia while negotiations are ongoing. It is anticipated that the interim arrangement will be replaced once negotiations are concluded.

The park also benefits from collaborations with a wide range of additional partners. Les Amis du Plein Air, the park’s co-operating association, runs Le Nique bookstore in the Chéticamp Visitor Centre. La Société Saint-Pierre works closely with the park to promote Acadian culture, language and community, as well as economic and tourism development of the region. Other key economic and business development partners include Ingonish Development Society, Destination Cape Breton Association and Tourism Nova Scotia. The park also works closely with the municipalities of the Counties of Inverness and Victoria, and with others related to emergency measures and wildfire management.

Map 1: Regional setting — Text version

An area map of the Atlantic provinces, showing the location of Cape Breton Highlands National Park in the northern part of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. A numbered legend lists other National Parks and Historic Sites of Canada administered by Parks Canada in Nova Scotia.

- Halifax Defence Complex: Halifax Citadel, York Redoubt, Fort McNab, Georges Island, Prince of Wales Tower

- Kejimkujik

- Port-Royal

- Grand-Pré

- Fort Anne

- Fort Edward

- Melanson Settlement

- Canso Islands

- Alexander Graham Bell

- Marconi

- Fortress of Louisbourg

- St. Peter's Canal

Map 2: Cape Breton Highlands National Park visitor services and facilities — Text version

A shaded contour map of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, showing the location of the Cabot trail, other paved and unpaved roads, hiking trails and access paths within the park. A symbol bank indicates the visitor services and facilities available at various locations. Trail names are given in a numbered list as follows:

- Acadian

- Salmon Pools

- Le Chemin Buttereau

- Le Buttereau

- Le vieux chemin du Cap-Rouge

- Corney Brook

- Skyline

- Bog

- Benjie’s Lake

- Fishing Cove

- MacIntosh Brook

- Lone Shieling

- Aspy

- Mica Hill

- Jack Pine

- Coastal

- Jigging Cove

- Green Cove

- Broad Cove Mountain

- Warren Lake

- Branch Pond Look-off

- Franey

- Clyburn Valley

- Middle Head

- Freshwater Lake Look-off

- Freshwater Lake

Development of the management plan

The draft management plan for Cape Breton Highlands National Park was prepared in consultation with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, as well as with input from key stakeholders and site partners including Les Amis du Plein Air co-operating association, la Société Saint-Pierre, local communities and two regional municipalities, local and regional economic development organizations, tourism operators and organizations, conservation groups and the province of Nova Scotia.

During the development of the draft management plan, the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia were engaged, particularly via the Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn Negotiation Office (KMKNO), and the Parks Canada—Mi’kmaq Unama’ki Advisory Committee. The draft plan was informally reviewed by KMKNO and the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources in March/April 2021; feedback from this informal review was incorporated into the draft plan. Further feedback was received on the draft plan during the final phase of consultation, and the plan has been further adjusted to reflect this. The plan was developed in the spirit and intent of the Recognition of Indigenous Rights and Self-Determination negotiations, with strong consideration given to key principles expressed by the Mi’kmaq. Management of the park will be consistent with outcomes of those negotiations.

In winter 2020, park stakeholders, local communities and the Canadian public were invited to provide input on a draft vision for the park and key management issues, to inform development of the draft plan. An online engagement platform attracted more than 1,200 visitors, and 204 people responded to the online survey. In-person stakeholder sessions and staff consultation sessions were also held. In fall 2021, stakeholders and the Canadian public were invited to review the draft plan posted on the park’s public website and provide feedback; nine written submissions were received from interested organizations and individuals. A staff session was also held, with feedback received through discussion and in writing. All feedback on the draft plan has informed development of this final plan.

Vision

The following outlines a 15 to 20-year vision for Cape Breton Highlands National Park.

With its dramatic coastline and diverse landscapes, Cape Breton Highlands National Park protects a representative example of the Maritime Acadian Highlands Natural Region for visitors to experience and enjoy for all time.

Situated in Unama’ki, a district of Mi’kma’ki, Cape Breton Highlands National Park has strong cultural and spiritual significance to the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia. The Mi’kmaq continue their stewardship of the park, sharing with Parks Canada in all aspects of park management guided by the Mi’kmaw principles of “two-eyed seeing” Footnote 3 and Netukulimk Footnote 4. The physical and spiritual connections of the Mi’kmaq to the park are strengthened and celebrated through a greater presence and use of the park by the Mi’kmaq including rights-based activities, and opportunities for economic benefit. The Mi’kmaq tell Mi’kmaw stories in their own voices.

The dynamic landscape of Cape Breton Highlands National Park adapts to a changing climate, supporting biodiversity through well-functioning ecosystems. The park’s cultural heritage is better understood and the cultural resources are conserved and presented, through collaboration with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and cultural communities. Environmental leadership is demonstrated at Cape Breton Highlands National Park, through investing in green technologies that support sustainable park operations.

Visitors attracted to the world-renowned Cabot Trail enjoy an extended stay, experiencing the park’s year-round outstanding hiking, camping and cycling offer. The offer is adapted to suit the needs, abilities and social identities of diverse visitors. More Canadians learn about the stories of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, including stories of past and present peoples and cultures.

Leading regional tourism and catalyzing growth in the northern Cape Breton economy, Parks Canada supports increased partnerships between Cape Breton Highlands National Park and neighbouring communities and businesses, supporting opportunities for regional prosperity.

Ula ewikasik ta’n ketu’-tl-lukutiek wejku’aql newtiska’q jel na’n te’sipunqekl mi’soqo tapuiskekipunqekl wjit Unama’kik Espaqmikek Kmitkinuey Anko’tasik Maqamikew: Tetuji wlamu’k pemjajika’sik aqq tel-mili-ankamkuk kmitkinu, Unama’kik Espaqmikek Kmitkinuey Anko’tasik Maqamikew anko’tmi’tij napeke’sikn Kji’kmukewey Wenujuey Espaqmikek Wksitqamuey Maqamikew wjit wenik Kanata kisi-nmitunew aqq l’ta’new ne’kaw.

Unama’kik Espaqmikek Kmitkinuey Anko’tasik Maqamikew etek Unama’kik, pkesikn Mi’kma’ki aqq ne’kaw kepmite’tmi’tij aqq ketlewite’tmi’tij Mi’kmaq wikultijik No’pa Sko’sia. Ne’kaw Mi’kmaq kelo’tmi’tij aqq anko’tmi’tij ula maqamikew, apoqntmi’tij teli-anko’tmumk ula maqamikew, ekina’mua’tiji Parks Kanata-ewe’k lukewinu’k tel-maliaptmumk maqamikew wije’wmumkl Mi’kmawe’l Kina’matnewe’l teluisikl Netuklimk aqq Etuaptmumk. Ta’n Mi’kmaq tel- kepmite’tmi’tij aqq ketlewite’tmi’tij ula maqamikew melkiknewa’tumk aqq wi’kipatmumk, alsumsultijik L’nu’k tli-alta’new aqq we’wmnew maqamikew wije’wmi’titl Mi’kmawe’l koqqwaja’taqnn aqq kisi-pkwatanew. Mi’kmaq a’tukwatmi’titl aknutmaqnmual ewe’wmi’tij wsitunuew.

Tel-pilua’sik maqamikew Unama’kik Espaqmikek Kmitkinuey Anko’tasik Maqamikew wije’wk tel-pilua’sikl teli-punqekl, mimaju’nik wsitqamuey aqq wela’toq telikwek koqoey kisoqe’k aqq apaqtuk. Telo’ltimkewey aji-wli-nsitmumk aqq Lnui-kjijitaqn anko’tmumk aqq ekina’muemk maw-lukutimkik No’pa Sko’siaewe’k Mi’kmaq aqq wutanl. Wsitqamuey Teli-wli-pma’tumk nemitumk Unama’kik Espaqmikek Kmitkinuey Anko’tasik Maqamikew, iko’tumk menaqaj teli-anko’tmumk wsitqamuey kulaman menaqaj tl-pmiatew tel-lukutimk na’te’l.

Wenik pejita’jik naji-alta’jik Cabot Trail kesatmi’tij siawqatmu’ti’tij elta’titl welamu’kl allika’timkl, etli-ktuknimkl aqq al-paysikla’mumkl etekl te’sipunqek, wjit ta’n pasik telaskma’tij aqq teli-ksua’lsulti’tij tel-milamuksultijik pejita’jik. Pemi-atelkik wenik Kanata pem-kina’masultijik aknutmaqnn wjit Unama’kik Espaqmikek Kmitkinuey Anko’tasik Maqamikew, we’kaw aknutmaqnn wjit wenik tleyawultijik tett aqq ta’n telo’ti’tij wejkwa’taqnik aqq kiskuk.

Nikana’tu’tij peji-mittukutimk aqq apoqntmi’tij teli-pkwatekemk Oqwatnuke’l Unama’kik, Parks Kanata apoqntik tel-maw-lukuti’tij Unama’kik Espaqmikek Kmitkinuey Anko’tasik Maqamikew aqq wutanl aqq mtmo’taqne’l etekl kiwto’qiw, apoqntmi’tij ta’n tl-wljaqo’ltiten tett.

Key strategies

Four key strategies are proposed for the management of Cape Breton Highlands National Park over the next ten years. The strategies and corresponding objectives and targets focus on achieving the vision through an integrated approach to park management. Targets have been prioritized with specific dates where feasible. Where no dates have been referenced, the target will be achieved within the period of the plan based on opportunities, annual priorities and capacity of Parks Canada. Annual implementation updates will be provided to the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, partners, stakeholders, and the general public.

Key strategy 1

A path to shared management with the Mi’kmaq

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia view Cape Breton Highlands National Park as a place of cultural and spiritual significance, being in Unama’ki, a district of Mi’kma’ki, the unceded and traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq. The Mi’kmaq have a greater presence on the land and a stronger role in management of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, including the undertaking of culturally significant harvesting activities.

Cape Breton Highlands National Park and the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia have a history of good relations, forged through collaborative research and management initiatives, such as the Bring Back the Boreal project Footnote 5. The current rights implementation negotiations context is anticipated to further outline a shared management role for the Mi’kmaq at the park; management in the interim is undertaken in the spirit and intent of those negotiations.

As well, the negotiations are anticipated to outline opportunities for economic benefits and employment for the Mi’kmaq related to Cape Breton Highlands National Park; meanwhile, Parks Canada will continue to explore opportunities with Mi’kmaw partners, particularly related to service provision in the park by Mi’kmaw businesses.

Parks Canada at Cape Breton Highlands National Park is well-positioned to support the Mi’kmaq in communicating with visitors and local communities about Mi’kmaw rights, as well as about Mi’kmaw culture and heritage. The park fosters opportunities for education and reconciliation between the Mi’kmaq and Cape Breton’s other cultural communities. Products and programs that contain Mi’kmaw content and are delivered by the Mi’kmaq in their own voices will satisfy visitor expectations for such information and inform the public on the role of the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia in park management and stewardship. Parks Canada aims to increase its presence and profile in Mi’kmaw communities, as well as supporting opportunities for the Mi’kmaq to reconnect with the park in meaningful ways.

Objective 1.1

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia are connected to Cape Breton Highlands National Park through an increased presence in the park and shared stewardship of park resources.

Targets

- Rights-based use of the park by the Mi’kmaq, including culturally significant harvesting activities, increases over the next five years.

- The number of events and celebrations held by the Mi’kmaq in the park increases over the next ten years from the 2019 baseline Footnote 6.

- The number of participants in youth and Elder camps held in the park increases by 30 percent over the next ten years from the 2019 baseline.

- By 2025, the number of Mi’kmaw businesses providing services within the park, including in collaboration with Parks Canada, increases.

- Parks Canada and the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia explore the possibility of introducing a Mi’kmaw name for the park within the life of the plan.

Objective 1.2

Through programming and outreach activities at Cape Breton Highlands National Park, visitors and local communities better understand Mi’kmaw rights, and the historic and contemporary use and culture of the Mi’kmaq in Unama’ki.

Targets

- Mi’kmaw content in visitor programs and materials increases, in collaboration with Mi’kmaw knowledge holders, from the 2019 baseline within the life of the plan.

- Informed in collaboration with the Mi’kmaq, Mi’kmaw terms and place names are increasingly incorporated into park programming, products and signage, where possible, from the 2019 baseline in the next five years.

- Within the life of the plan, the park continues to serve as a place for education and reconciliation between Mi’kmaq and Cape Breton’s other cultural communities.

Objective 1.3

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and Parks Canada share the management of Cape Breton Highlands National Park in a collaborative and respectful manner.

Target

- Organizational structures are in place and functioning in support of shared management of Cape Breton Highlands National Park by the Mi’kmaq and Parks Canada within the life of the plan.

Key strategy 2

Shared conservation in the context of change

Conservation of Cape Breton Highlands National Park benefits from a “two-eyed seeing” approach, where Western and Mi’kmaw knowledge combine to inform decision making. The ecological integrity of Cape Breton Highlands National Park is a primary consideration in all park management decisions and park ecosystems sustain biodiversity and key species.

Climate change and other landscape level ecosystem changes will have a profound effect on all aspects of park management, particularly ecosystem conservation. Projected changes in temperature and precipitation patterns and resultant shifts in habitats may create conditions more favourable for non-native and invasive species. With impacts such as coastal erosion and intense storms, climate change may also affect other aspects of park management, including cultural resources, built assets, transportation and visitor experience. There remains a need for better understanding of the role of fire in the forest ecology of the park, and management of vegetation around key park infrastructure and adjacent communities to reduce wildfire risk. Forest composition is projected to change through time as species ranges shift. Moose management can increase vegetation growth promoting healthy, diverse forested landscapes, which offer the potential for increased carbon sequestration.

Park managers are working with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources and other partners to build understanding and restore the habitat of species that are threatened or at risk in the park, including Canada lynx, American pine marten, myotis bats, Bicknell’s thrush, Canada warbler, olive-sided flycatcher, and Atlantic salmon, by supporting their recovery. A species at risk site analysis, prepared in 2017–2018, provides guidance on supporting the recovery of species at risk within and surrounding the park; this will be updated within this planning cycle.

Parks Canada also works with other levels of government and organizations beyond park boundaries, to enhance broader landscape connectivity. The increased protection of the Cape Breton Highlands ecosystem generally, through additional protected areas and increased terrestrial, freshwater and marine connectivity, contributes to the ecological integrity and resiliency of Cape Breton Highlands National Park. Parks Canada supports the creation of new Indigenous protected and conserved areas (IPCAs) within the Cape Breton Highlands ecosystem, such as Kluskap IPCA.

Also important is the conservation and presentation of the park’s cultural resources. There is currently limited knowledge of the cultural resources in the park, but having a better understanding and documentation of the history of the park and its cultural resources will allow these considerations to inform park management. A cultural resources values statement for the park will be initiated within the life of the plan, to inform management of the park’s cultural heritage, particularly initial steps such as consultation with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, local communities and staff; and the identification of cultural resources in the park.

In partnership with others, Parks Canada will take note of emerging conservation issues not actively monitored and pursue management strategies in collaboration with conservation partners as appropriate. Including many partners, perspectives and diverse knowledge sources in park management brings a diversity and breadth of experience to respond to environmental changes.

Cape Breton Highlands National Park should continue to serve as a site of excellence for ecological restoration, research and science, contributing to the body of peer-reviewed research related to northern Cape Breton ecosystems and cultural heritage. This concept builds on increasing partnerships, particularly toward collaborative landscape-scale conservation, which will benefit the ecological integrity and the conservation of cultural resources of the park. There are opportunities for exchange and collaboration between managers of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, provincial protected areas, and Indigenous protected and conserved areas, in terms of information, resource sharing and joint projects.

Objective 2.1

Western and Mi’kmaw knowledge related to park ecosystems and the broader landscape (“two-eyed seeing”) contribute to better understanding of natural and cultural conservation issues, ecosystems and species at risk, supporting integrated, evidence-based decision-making for the management of Cape Breton Highlands National Park.

Targets

- Mechanisms and structures (e.g. steering committees) to facilitate the participation of local knowledge holders, including the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, and academics in key conservation issues are established over the next five years.

- The ecological integrity monitoring program of Cape Breton Highlands National Park is reviewed and updated to reflect both Western and Mi’kmaw knowledge within the life of the plan.

- Understanding of the distribution and abundance within the park of species of interest to the Mi’kmaq (e.g. black ash) increases within the life of the plan.

Objective 2.2

The state of the forest ecosystems within Cape Breton Highlands National Park shows a stable or improving trend.

Targets

- The forest area measure of the forest ecosystems indicator for Cape Breton Highlands National Park shows a stable or improving trend from “Poor” and stable by the next state of the park assessment Footnote 7.

- The moose abundance measure of the forest ecosystems indicator for Cape Breton Highlands National Park shows a stable or improving trend from “Good” and stable by the next state of the park assessment.

- Knowledge of the role of fire and connectivity in forest ecosystems increases by 2025.

Objective 2.3

The health of Atlantic salmon populations within Cape Breton Highlands National Park is maintained or improves.

Targets

- The fish health measure of the freshwater indicator for Cape Breton Highlands National Park shows a stable or improving trend from “Fair” and stable by the next state of the park assessment.

- The co-development of a management plan for the Chéticamp River within the life of the plan, with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources and other partners, contributing to improved relationships, cultural sharing, and a multifaceted understanding of the rivers’ salmonid populations through shared assessment activities.

- The first stage of a Parks Canada-funded project related to the restoration of Atlantic salmon in the Clyburn Brook (eastern Cape Breton, endangered) is completed by 2025.

Objective 2.4

Cultural resources in Cape Breton Highlands National Park are better understood and documented, in collaboration with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and other cultural communities and knowledge holders.

Targets

- Initial steps of a cultural resources values statement for Cape Breton Highlands National Park are undertaken within the next five years, with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and other knowledge holders, to inform all management decisions within the park.

- The cultural heritage of the park and surrounding region is better understood and communicated within the life of the plan (e.g. collaboration with Mi’kmaq knowledge holders on traditional use and documentation of Indigenous sites, and sharing Acadian stories in collaboration with La Société Saint-Pierre).

Objective 2.5

Climate change impacts on the broader landscape, as well as on ecosystems and cultural resources of Cape Breton Highlands National Park and their implications for park management, are better understood.

Targets

- Scenario planning activities related to climate change impacts on the park are undertaken within the next five years.

- Climate change adaptation and mitigation options for projected climate change scenarios are identified within the next ten years.

- Community science and research with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources and other university and government partners (e.g. phenology cameras Footnote 8; coastal erosion monitoring study with Nova Scotia Environment; paleo-environmental study with Queens University; connectivity modelling with Dalhousie University) related to increased understanding of climate change continues to occur through the life of this plan.

Key strategy 3

A destination inspired by community, nature and culture

An anchor in the regional tourism industry, Cape Breton Highlands National Park is an important local partner in sustainable tourism. High-quality experiences unique to Cape Breton encourage visitors to stay longer both within and outside of the park, benefitting local communities and the park. Mi’kmaw and local businesses recognize opportunities for providing programs and services such as cultural or experiential programs, and guiding or food services to park visitors; Parks Canada works with prospective providers to determine the kinds of services that might be appropriate in the park.

Stakeholders and local communities have indicated a desire for a year-round offer at Cape Breton Highlands National Park. Cape Breton is one of the few places in Nova Scotia with reliable snow and winter conditions (although this may change with climate change), and the park has the land base and trail network to attract winter enthusiasts. Currently, visitors are encouraged to enjoy the park in winter and are informed of limited services. The park has also partnered on winter activities in recent years with local community groups. Expanding on these winter activities in the park should be done in collaboration with local communities providing supplemental services, such as food and lodging. It should be noted that although several stakeholders voiced an interest in snowmobiling during consultation for this plan, recreational snowmobiling within the park is not permitted and will not be contemplated as part of a winter offer.

The park is well known for hiking. There is interest in a long-distance, more challenging hiking offer in the park, possibly supplemented with rustic accommodations such as cabins, or linkages of the trail system with the surrounding communities to support active transportation. The trail offer in the park is being reviewed, including the exploration of a series of frontcountry trails linking key nodes along the Cabot Trail. Opportunities to expand the trail system to accommodate mountain biking might also be a possibility. As well, diversified accommodations have proven popular, complementing traditional camping. Further testing and installation of diversified accommodations in the park, such as more oTENTiks and other types, will be explored within the life of the plan.

Many visitors have an interest in history and culture and seek information about the full scope of human history of the park. This might include historic and contemporary Mi’kmaw use and culture; European immigration and settlement, including the communities and families affected by expropriation related to the park; and local communities’ contemporary culture and traditions, such as food, work, songs and stories. Over the life of this plan, expanded programming will be explored in collaboration with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and other cultural communities and knowledge holders.

Visitation numbers in Cape Breton Highlands National Park showed steady increase over the five years prior to 2019–2020. Although visitation remained within levels the park could accommodate, some park features (e.g. Skyline Trail) were receiving high levels of visitation at certain times of the year. Despite significant visitation declines initially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the requirements to maintain social distancing and other safety measures meant that some areas continued to reach their limit in terms of capacity. Guiding visitors toward other less-visited features in the park, thanks to lessons learned through managing congestion at high-traffic features, could contribute to visitors’ experience and ecological integrity.

Visitation patterns initially shifted toward more local tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic due to travel restrictions. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of protected areas for mental and physical health. While it is difficult to predict how travel patterns may change as the pandemic continues to evolve, this has brought a new opportunity to reconnect local visitors to the national park and potentially strengthen a base of supporters and volunteers. Parks Canada will make a concerted effort to retain local repeat visitors, as well as attract new visitors from target markets, particularly young families, young adults, racialized communities and urban audiences, through its online presence and social media campaigns.

Awareness building and outreach activities will continue, to increase the relevance of Cape Breton Highlands National Park to Canadians and the awareness of protected areas in general, to communicate about how to be a responsible visitor and to motivate travel, with more focus on a digital approach. A variety of means and opportunities, such as social media, media, travel trade, outreach events and partner engagement, in person and virtually, will continue to be used to reach target audiences. Parks Canada will work with diverse communities, including racialized communities, to help them connect with the park and reduce barriers. Reaching local school-aged children virtually and through in-park programming is a means of encouraging future park advocates.

Objective 3.1

The visitor experience offer in Cape Breton Highlands National Park meets the needs of diverse audiences.

Targets

- Within the life of the plan, visitor experience decision making, including visitor use management, is informed by strategic planning that reflects regional, national and international tourism contexts, while ensuring cultural and natural heritage conservation and sustainability.

- The number of surveyed visitors who are satisfied with their overall visit continues to meet or exceed 90 percent by the next state of the park assessment.

Objective 3.2

The rich cultural heritage of Cape Breton Highlands National Park is shared with Canadians and visitors and celebrated with communities.

Targets

- The number of products and programs that communicate the histories and cultures of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, prepared and delivered in collaboration with Mi’kmaw partners and other knowledge holders, increases from the 2019 baseline over the next five years.

- The percentage of surveyed visitors who feel they learned something about the cultural heritage of the park continues to meet or exceed 60 percent by the next state of the park assessment.

Objective 3.3

Visitors have opportunities to appreciate and experience Cape Breton Highlands National Park year-round, increasing opportunities to deepen visitors’ connections to the park.

Targets

- Visitor experiences during the winter season are piloted in collaboration with local and Mi’kmaw businesses and communities at Cape Breton Highlands National Park within the next five years.

- An enhanced strategy centred on itineraries and packages available to visitors, in collaboration with local service providers, is developed and delivered over the next five years.

Objective 3.4

The accommodations offer in the park is enhanced (i.e. the existing offer is improved or new, diversified accommodations are offered), responding to target market needs and expectations.

Targets

- The number of units of diversified accommodations within the park increases over the next five years from the 2019 baseline (e.g. Trout Brook off-grid campground).

- The percentage of visitors who stayed one or more nights in the park increases from 2019 levels by the next state of the park assessment.

Objective 3.5

The trail offer in the park supports accessible, active transportation between Cape Breton Highlands National Park and its surrounding communities, with opportunities for multiple types of human-powered adventure.

Targets

- At least one trail-use project is piloted over the next ten years in collaboration with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia.

Objective 3.6

Cape Breton Highlands National Park provides increased opportunities for local and Mi’kmaw businesses to operate in the park to fill service and experience gaps (e.g. outfitters, guides, food service).

Targets

- By 2025, the number of local and Mi’kmaw businesses providing services within the park, including in collaboration with Parks Canada, increases from zero (2019 baseline).

- Parks Canada regularly communicates with local and Mi’kmaw businesses about service provision opportunities appropriate for the park by 2023.

Objective 3.7

Visitation to Cape Breton Highlands National Park is managed so that it is sustainable.

Targets

- An analysis of visitor use through the visitor use management framework is completed for high-traffic locations within the park by 2025 (e.g. Skyline Trail).

- Demands on key features are lowered over the next five years, reducing impacts on infrastructure and the environment through means such as visitor use dispersion or other best practices in visitor use management.

Objective 3.8

The number of Canadians engaged by and demonstrating awareness and support for Cape Breton Highlands National Park increases.

Targets

- Parks Canada’s collaboration with strategic partners to reach key audiences and markets increases within the next five years.

- Outreach and promotion initiatives in urban and suburban areas increase from the 2019 baseline within the life of the plan.

- A higher proportion of Canadians engaged by the park originate from new target markets, including urban dwellers, racialized communities, young families, young adults and new Canadians from the 2019 baseline within the life of the plan.

Key strategy 4

Optimizing operations to connect canadians with Cape Breton Highlands National Park

Cape Breton Highlands National Park has considerable aging, unused or underused facilities and infrastructure, which need to be evaluated for their potential for repurposing or divestment. Such an “optimizing” of infrastructure and operations in the park provides an opportunity to incorporate priority considerations. These include maintaining or increasing ecological integrity, greening operations (i.e. increasing energy efficiency and reducing greenhouse gases, utilizing environmentally friendly materials) as per the Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy, public health and safety, principles of inclusion and universal accessibility, and climate change mitigation and adaptation. This key strategy focuses on improving general asset conditions and park operations, particularly contributing to climate change action through partnerships with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and service providers.

With an aging Canadian population, and seeking to attract new target markets (e.g. young families, young adults, racialized communities, urban Canadians), facilities and services within the park need to be suited to diverse interests and able to welcome and accommodate many different needs and abilities. Efforts will be made to increase digital connectivity within the park, including increased cell phone coverage and internet access, although the geography of the park poses challenges. As existing infrastructure is upgraded, and as new infrastructure is designed, there are opportunities to reduce barriers in accordance with the Accessible Canada Act. This might include such things as retrofitting buildings and ensuring trail design accommodates a range of abilities. As well, any redesign should consider providing expanded outdoor experience opportunities for Canadians in the park, with appropriate mitigations for public health and safety.

Cape Breton Highlands National Park is well-positioned to be a model of environmental leadership, showcasing new technologies and demonstrating their feasibility to visitors, local communities and Canadians at large. This can help change attitudes and opinions about such technologies and increase support for them. The installation of electric-car charging stations in the park, as well as adopting heating and power alternatives (e.g. solar power at the new campground at Trout Brook), are tangible examples of greening operations and demonstrating environmental leadership at the park.

Objective 4.1

Park infrastructure meets current and projected operational needs.

Targets

- Assessment of park infrastructure, prioritizing aging or underused assets, is undertaken by 2027, taking into consideration the assets’ conservation value to species at risk that may rely on human structures as habitat.

- Divestment and repurposing of key assets occurs as opportunities arise within the life of the plan.

Objective 4.2

The abilities, needs and social identities of a diverse visitor base are more fully accommodated at Cape Breton Highlands National Park, in terms of accessibility and inclusion.

Targets

- Existing infrastructure (e.g. trails, facilities) is updated as opportunities arise and new infrastructure incorporates design principles, as feasible, to meet the diverse abilities, needs and social identities of visitors within the life of the plan.

- Cell phone coverage and internet access within the park, for both public safety and visitor experience, is increased as feasible within the life of the plan.

- Demonstrable improvement of the park’s accessibility and inclusion through an audit, from the 2019 baseline, within the life of the plan.

Objective 4.3

Cape Breton Highlands National Park demonstrates environmental leadership including climate change mitigation and green procurement.

Targets

- Greenhouse gas emissions from park operations are reduced by at least 40 percent from 2005 levels by 2030 (with an aspiration to achieve this by 2025).

- At least 40 percent Cape Breton Highlands National Park light fleet vehicles (i.e. 15 of 38) are electric/hybrid by 2025.

Objective 4.4

Climate change effects on built assets is addressed within Cape Breton Highlands National Park through a range of measures, including monitoring, adaptation and increased resilience.

Targets

- Cape Breton Highlands National Park undertakes at least one wildfire risk reduction project every two years within the life of the plan.

- Scenario planning activities with partners related to climate change impacts on the park, particularly on built assets including roadways, are undertaken by 2025 (e.g. coastal erosion study).

- Strategies and tactics to respond to climate change impacts are co-developed with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources and other partners as related to key park management functions within the life of the plan.

- Requirements for asset maintenance due to climate change impacts are reduced within the life of the plan.

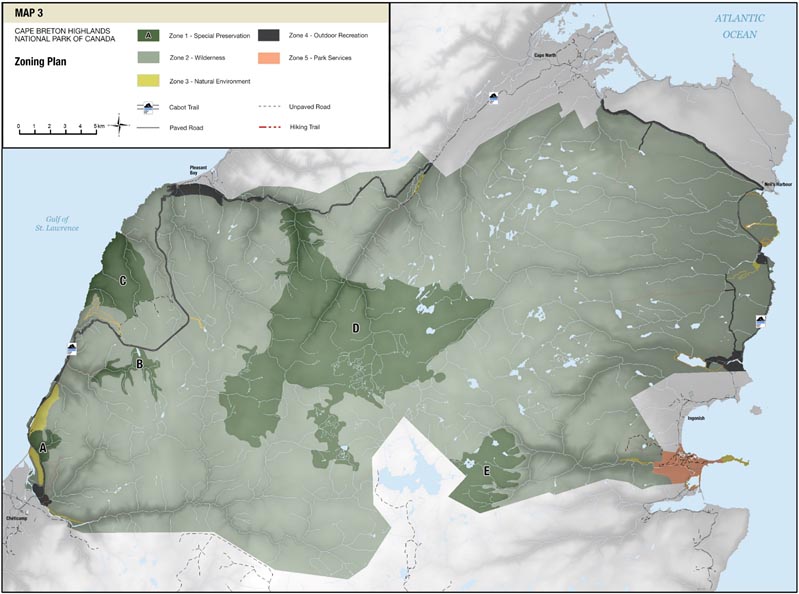

Zoning and declared wilderness area

Zoning

Parks Canada’s national park zoning system is an integrated approach to the classification of land and water areas in a national park and designates where particular activities can occur on land or water based on the ability to support those uses. The zoning system has five categories:

- Zone I - Special Preservation;

- Zone II - Wilderness;

- Zone III - Natural Environment;

- Zone IV - Outdoor Recreation; and

- Zone V - Park Services.

Zoning plans are based on the best available information about natural and cultural resources and visitor experience and are modified if necessary. They are reviewed every ten years as part of the management plan review process. No changes were made to Cape Breton Highlands National Park zoning since the 2010 management plan; however, improved technologies that can more accurately present zone boundaries have led to some adjustments in percentage area of some zone categories (Map 3). In the future, park zoning will be informed by increased information about the natural and cultural resources of the park, as it becomes available.

Zone I – Special preservation

Zone I areas provide an increased level of protection for the most sensitive or representative natural features and threatened cultural resources. Public motorized access (including both vehicles and motorized boat use) is not permitted. Opportunities are provided for visitors to experience and learn about these unique areas in a manner that does not threaten their values.

There are five Zone I areas in Cape Breton Highlands National Park, representing 15.6 percent of the total area. These areas include (but are not limited to) areas that contain rare or endangered species. (See Appendix A for a description of Zone I areas.)

Zone II – Wilderness

Zone II areas are conserved in a wilderness condition with minimal interference. They provide high-quality backcountry opportunities for visitors to experience wilderness, including remoteness and solitude, with a high degree of visitor self-reliance and minimal built structures. Public motorized access is not permitted.

Zone II areas represent 81 percent of the total area of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, and encompass most of the area not immediately adjacent to the Cabot Trail.

Zone III – Natural environment

Zone III areas are managed as natural areas where impacts are minimized and mitigated to the extent possible/feasible. Zone III areas provide high quality frontcountry opportunities to experience and learn about the natural and cultural environment and are supported by minimal facilities of a rustic nature. While public motorized access may be allowed in Zone III areas, it will be controlled and public transportation is encouraged.

Zone III areas encompass 0.6 percent of the total area of Cape Breton Highlands National Park.

Zone IV – Outdoor recreation

Zone IV areas are small areas that support intensive visitor use and infrastructure such as campgrounds, beach facilities, roads, and parking areas. Zone IV areas offer high-quality frontcountry recreational and learning opportunities with an emphasis on accessibility and safety.

Zone IV areas encompass 2 percent of the total area of Cape Breton Highlands National Park.

Zone V – Park services

Zone V designation has been given to the Ingonish Headquarters area owing to its concentration of visitor-support services, park administration functions, and outdoor recreational opportunities. Motorized access is acceptable in Zone V, but protection of natural values is important.

Zone V areas encompass 0.5 percent of the total area of Cape Breton Highlands National Park.

Wilderness area declaration

The intent of legally designating a portion of a national park as wilderness is to maintain its wilderness character in perpetuity. Only activities that are unlikely to impair the wilderness character of the area may be authorized within the declared wilderness area of Cape Breton Highlands National Park.

In Cape Breton Highlands National Park, a wilderness area had been tentatively identified in the 2010 management plan with the intention that it would be further considered during the next round of management planning. A wilderness area will be considered for Cape Breton Highlands National Park during a future management plan review.

Map 3: Cape Breton Highlands National Park zoning plan — Text version

A reference map of the Cape Breton Highlands National Park showing five color-coded areas, as follows:

- Zone 1: Special Preservation

- Zone 2: Wilderness

- Zone 3: Natural Environment

- Zone 4: Outdoor Recreation

- Zone 5: Park Services

The map also shows the route of the Cabot trail, other paved and unpaved roads, and hiking trails. There are five special preservation areas of various size indicated on the map, labelled A, B, C, D, and E respectively. Outdoor recreation areas are found primarily along the Cabot Trail, Park Services are concentrated in the area of Ingonish, and natural environments are interspersed throughout the park, primarily in coastal areas and along waterways. The remainder of the park is comprised of wilderness.

Summary of strategic environmental assessment

All national park management plans are assessed through a strategic environmental assessment to understand the potential for cumulative effects. This understanding contributes to evidence-based decision-making that supports ecological integrity being maintained or restored within the life of the plan. The strategic environmental assessment for the management plan for Cape Breton Highlands National Park considered the potential impacts of climate change, local and regional activities around the park, expected increase in visitation and proposals within the management plan. The strategic environmental assessment assessed the potential impacts on different aspects of the ecosystem, including forests, freshwater, and wetland ecosystems and wetland species, as well as Bicknell’s thrush, Atlantic salmon, and other species at risk.

The management plan will result in many positive impacts on the natural environment, maintaining and improving landscape connectivity in the region within the context of climate change. The initiatives include the maintenance and improvement of ecological integrity, and initiatives to facilitate participation of local knowledge holders and academics to work on conservation issues within the broader landscape. The weaving of Western science and Mi’kmaw knowledge will promote evidence-based decision-making that supports the management of ecological integrity within the park.

Forest ecosystems are subject to cumulative effects due to a hyper abundant moose population impairing regeneration following an historical outbreak of the natural spruce budworm, as well as external forest management and use, and development. Climate change is likely to further contribute to poor regeneration of some forest species in the region in the long term. As an island ecosystem, forest-dependent species are already subject to fragmented, and potentially isolated habitats; additional pressures on landscape connectivity in the region would contribute to negative, cumulative effects on these species. The proposed long-distance trail and rustic accommodations and a year-round visitor offer could contribute to incremental habitat loss and fragmentation of forest habitat and alter wildlife habitat use patterns in these habitats. Project-level impact assessments, continued monitoring, initiatives to improve the forest ecosystem and collaborative partnerships, most notably with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources and local universities, to improve understanding the park’s contribution to landscape connectivity are underway to support the mitigation of potential adverse impacts to forest ecosystems.

Species such as the Atlantic salmon and American eel are subject to cumulative impacts throughout their lifecycles, both in the marine and freshwater environments. Habitat modification, external activities such as forest management and use, climate change, pollution and at-sea conditions contribute to cumulative effects for these species. While the proposed long-distance trail may interact with freshwater habitat, with the implementation of appropriate design and site-specific mitigation measures, the trail is not anticipated to contribute to long-term cumulative impacts on freshwater habitat. Initiatives to develop a baseline understanding of Atlantic salmon populations in Chéticamp River, in collaboration with the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources and regional partners, is anticipated to contribute to the park’s ability to develop targeted strategies to continue to support the recovery of salmon populations. An Atlantic salmon recovery program that is specifically targeted at the restoration of eastern Cape Breton Atlantic salmon to Clyburn Brook is also anticipated to facilitate species recovery.

Wetlands and other freshwater ecosystems are subject to cumulative impacts from external factors such as forest management and use, the Wreck Cove hydroelectric dam, pollutants from runoff from adjacent roadways, as well as landscape-level stressors, such as climate change. With some uncertainties in the wetland ecological integrity measures, they will be reviewed and updated to facilitate better understanding of conservation issues.

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, partners, stakeholders and the public were consulted on the draft management plan and the summary of the draft strategic environmental assessment. Feedback was considered and incorporated into the strategic environmental assessment and management plan as appropriate.

The strategic environmental assessment was conducted in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals (2010) and facilitated an evaluation of how the management plan contributed to the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. Individual projects undertaken to implement management plan objectives at the site will be evaluated to determine if an impact assessment is required under the Impact Assessment Act, or successor legislation. The management plan supports the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy goals of greening government, sustainably managed lands and forests, healthy wildlife populations, connecting Canadians with nature, and safe and healthy communities.

Many positive environmental effects are expected and there are no important negative environmental effects anticipated from implementation of the Cape Breton Highlands National Park management plan.

Appendix A: Zone I descriptions

There are five Zone I areas within Cape Breton Highlands National Park (see Map 3):

A. Grande Falaise:

Contains the best example in the Maritime Acadian Highlands Natural Region, and possibly in the Maritime provinces, of a spectacular cliff and very large talus slope of granitic rock. Seven species of arctic-alpine plants considered rare in the natural region occur here, along with good habitat for the rock vole, Gaspé and pygmy shrew (all of which are rare). The upper reaches of the cliff contain white spruce krummholz. This zone protects a portion of the Acadian land region.

B. Corney Brook – French Lake:

Contains a site with both raised and sloping bogs and good representation of bog ecosystems in the natural region. The upper portions of the Corney Brook Valley support some of the 26 arctic-alpine plants that are rare in the Maritime Acadian Highlands Natural Region, and is good habitat for representative populations of songbirds, lynx, marten and garter snakes. This zone protects portions of both Acadian and boreal land types.

C. George Brook Coastal Area:

Contains rare dwarf or shrub birch, representative talus slopes, salt barrens and a representative portion of Gulf of St. Lawrence coast landscape and vegetation communities. Both Acadian and boreal land types are protected here.

D. Grand Anse River – Interior Plateau:

Contains a site which is the best example in the natural region of an old-growth Acadian forest, and provides important habitat for six species of rare arctic-alpine plants, rare rock vole and Gaspé shrew, songbirds and other avifauna, reptiles, trout and Atlantic salmon. This site contains the largest concentration of rare arctic-alpine plants in the Maritime provinces (some 25 species in the Big Southwest Brook area), and the headwaters and reservoir area of most major park rivers. This complex area also provides the best examples in the Maritime Acadian Highlands Natural Region of all stages of ombrotrophic bog processes, raised sphagnum bogs and the park’s only two known concentric domed bogs. Important habitat of the rare greater yellowlegs, the rare marten, bog lemming, lynx (rare in the Maritime provinces), trout, and salmon is also found here.

E. Two Island Lake:

Contains the best example in eastern Canada of periglacial-like formations, deflation mound patterns, and cryogenic processes, and an excellent example of a barren highland plateau, which is unique in the Maritime provinces. This area also provides habitat for greater yellowlegs, southern bog lemming and grey-cheeked thrush, and a limited number of rare arctic-alpine plant species.

Contact us

For more information about the management plan or about Cape Breton Highlands National Park:

Cape Breton Highlands National Park

Ingonish Beach NS B0C 1L0

Publication information

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President & Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2022.

Front cover image credits

top from left to right: E. Madinsky/©Parks Canada, J. Felix/©Parks Canada, C. Wrathall/©Parks Canada

bottom: A. Hill/©Parks Canada

PDF: R64-105/84-2002E-PDF

Paper: 978-0-660-41213-9

Related links

- Date modified :