Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan, 2024

Fundy National Park

On this page

- Foreword

- Recommendations

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Significance of Fundy National Park

- 3.0 Planning context

- 4.0 Development of the management plan

- 5.0 Vision

- 6.0 Key strategies

- 7.0 Zoning and declared wilderness area

- 8.0 Summary of strategic environmental assessment

- Appendix A Environmentally sensitive sites

- Footnotes

Foreword

From coast to coast to coast, national historic sites, national parks and national marine conservation areas are a source of shared pride for Canadians. They reflect Canada’s natural and cultural heritage and tell stories of who we are, including the historic and contemporary contributions of Indigenous peoples.

These cherished places are a priority for the Government of Canada. We are committed to protecting natural and cultural heritage, expanding the system of protected places, and contributing to the recovery of species at risk.

At the same time, we continue to offer new and innovative visitor and outreach programs and activities to ensure that more Canadians can experience these iconic destinations and learn about history, culture and the environment.

In collaboration with Indigenous communities and key partners, Parks Canada conserves and protects national historic sites and national parks; enables people to discover and connect with history and nature; and helps sustain the economic value of these places for local and regional communities.

This new management plan for Fundy National Park of Canada supports this vision.

Management plans are developed by a dedicated team at Parks Canada through extensive consultation and input from Indigenous partners, other partners and stakeholders, local communities, as well as visitors past and present. I would like to thank everyone who contributed to this plan for their commitment and spirit of cooperation.

As the Minister responsible for Parks Canada, I applaud this collaborative effort and I am pleased to approve the Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan.

Recommendations

Recommended by:

Ron Hallman

President & Chief Executive Officer

Parks Canada

Andrew Campbell

Senior Vice-President, Operations Directorate

Parks Canada

Julie M. LeBlanc

Superintendent

New Brunswick South Field Unit

Parks Canada

Executive summary

Fundy National Park is located in the Mi’gmaq district of Signigt’gewa’gi. Often referred to as Siknikt, Signigt’gewa’gi is a Mi’gmaq word which translates to “drainage area” in English, as this was an area with many rivers and waterways that received the meltwaters of the glaciers as they receded northward.

As a key tourism destination in southern New Brunswick, Fundy National Park welcomes over 300,000 visitors per year to enjoy spectacular ocean views and landscapes, camping, hiking, biking, and other outdoor recreation. The neighbouring community of Alma supports a vibrant fishing industry which complements the national park experience with the daily activities of a working wharf within walking distance of the park entrance.

Fundy National Park continues to collaborate with Mi’gmaq and Wolastoqey Nations including the Parks Canada and Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn Incorporated (MTI) Advisory Committee Table, which meets at regular intervals. Considerable progress has also been made with partners in active management and recovery of species at risk, notably improving the ecological integrity of the aquatic ecosystem which has shown five-year trends in increasing numbers of salmon and establishing Parks Canada’s first research chair in the Atlantic region. Fort Folly Habitat Recovery has been integral in salmon restoration and sharing Mi’gmaq knowledge in a scientific and holistic approach.

A 2020 State of the Park Assessment reconfirmed the general direction from the 2011 management plan with continued focus on active management to increase the sustainability of all park operations, maintaining and improving ecological integrity, improving relationships and collaborations with Indigenous nations, and increasing knowledge of cultural resources.

Sustainable operations are essential to advance cooperative management with Indigenous partners, protect park ecosystems, ensure the well-being of staff, the enjoyment of visitors and the success of the local economy. Most importantly, sustainable park operations are key to fully realizing the objectives presented in this management plan over the next decade.

The four key strategies for the ten-year management plan period focus on the following:

Key strategy 1

Grow together, learn together

The intent of this strategy is to move toward cooperative management of Fundy National Park while at the same time learning more about the cultural use and history of the Fundy region with a focus on weaving Indigenous languages, cultures, history, priorities, rights and interests into park operations. In collaboration with Indigenous partners and community stakeholders, a better understanding of Indigenous and Euro-Canadian history will be developed through a cultural resource values statement which will identify the park’s cultural value in the review of the past and current significance of the location.

Key strategy 2

Working together to improve ecological integrity and connectivity

This strategy will advance priority monitoring and active management within the park and will establish more collaborations with partners outside of the park toward improved ecological connectivity in the broader landscape. Inside the park, monitoring will include Indigenous knowledge guiding decisions for active management with a focus on at-risk and culturally important species. Managing the operational footprint, understanding the effects of climate change on ecological processes, and implementing approaches for climate change adaptation will also be a priority.

Key strategy 3

Climate resilient and sustainable operations support the delivery of the core mandate and the character of Fundy National Park

Aligning operational requirements with available resources is a key focus of this strategy. Fundy National Park has an extensive inventory of assets that are original and beyond functional lifespans. To deliver Parks Canada’s core mandate with quality services and experiences for families, campers and hikers, and other target markets, over the next ten years and beyond, a focus on realistic maintenance capacity within existing resources is critical. Strategic assessment of the long-term viability of park operations is required.

Key strategy 4

Authentic, sustainable, memory-making experiences

Fundy National Park experiences high visitation during its year-round operations, which supports regional economic development in cooperation with partners and the tourism industry. A fully accessible visitor experience, from planning to arrival to departure, will be prioritized in this key strategy along with a focus on a sustainable trail network. Protection of ecological integrity will guide visitor use management approaches for popular visitor use areas.

1.0 Introduction

Parks Canada administers one of the finest and most extensive systems of protected natural and historic places in the world. Parks Canada’s mandate is to protect and present these places for the benefit and enjoyment of current and future generations. Future-oriented, strategic management of each national historic site, national park, national marine conservation area and heritage canal administered by Parks Canada supports its vision:

Canada’s treasured natural and historic places will be a living legacy, connecting hearts and minds to a stronger, deeper understanding of the very essence of Canada.

The Canada National Parks Act and the Parks Canada Agency Act require Parks Canada to prepare a management plan for each national park. The Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan, once approved by the Minister responsible for Parks Canada and tabled in Parliament, ensures Parks Canada’s accountability to Canadians, outlining how park management will achieve measurable results in support of its mandate.

First Nations, stakeholders, partners and the Canadian public were involved in the preparation of the management plan, helping to shape the future direction of the national park. The plan sets clear, strategic direction for the management and operation of Fundy National Park by articulating a vision, key strategies and objectives. Parks Canada will report annually on progress toward achieving the plan objectives and will review the plan every ten years or sooner if required.

This plan is not an end in and of itself. Parks Canada will maintain an open dialogue on the implementation of the management plan, to ensure that it remains relevant and meaningful. The plan will serve as the focus for ongoing engagement and, where appropriate, consultation, on the management of Fundy National Park in years to come.

2.0 Significance of Fundy National Park

Parks Canada acknowledges the lands upon which we gather in New Brunswick to be the unceded territories of the Mi’gmaq, Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati Nations.

Fundy National Park was established in 1948. It protects 206 square kilometres of the Fundy Coast Ecoregion which includes sheltered coves, salt marshes, estuaries and rugged cliffs that rise 150 metres from the Bay of Fundy, which is home to the highest tides in the world at over 11 metres. Fundy National Park also includes the Southern Uplands Ecoregion. This natural region is characterized by a rolling, hilly plateau cut by deep valleys and cascading rivers. Within the Southern Uplands Ecoregion, the topography reaches over 400 metres, with the Upper Salmon River, Point Wolfe River, and Goose River carving steep sided ravines down to the coast. While it does not include marine components or the intertidal zone, the national park protects the coast and spectacular view planes looking out to the Bay of Fundy and across to the northwestern coast of Nova Scotia. Fundy National Park is considered the core of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Fundy Biosphere Region, designated in 2007 to protect and encourage sustainable tourism in the biosphere region.

The Fundy National Park area is also rich in human history stories – distinct to the Upper Bay of Fundy – stories yet to be uncovered and communicated in discovering the rich traditional and cultural values and experiences of the diverse communities and families deeply rooted in this part of New Brunswick.

One of the most important attractions for visitors to the region and to Fundy National Park is to experience the tides and tidal flats. The dramatic impact and size of the tides – the highest in the world! – can be seen in the rise and fall of the local fishing fleet tied to the wharf in Alma, at times sitting on the ocean floor. Known as the “Land of Salt and Fir”, the landscapes, climate and biodiversity of Fundy National Park are directly linked to the ocean and its immense tides. The awe-inspiring views and wide vistas up and down the coast characterize the special nature of Fundy National Park.

3.0 Planning context

In this section

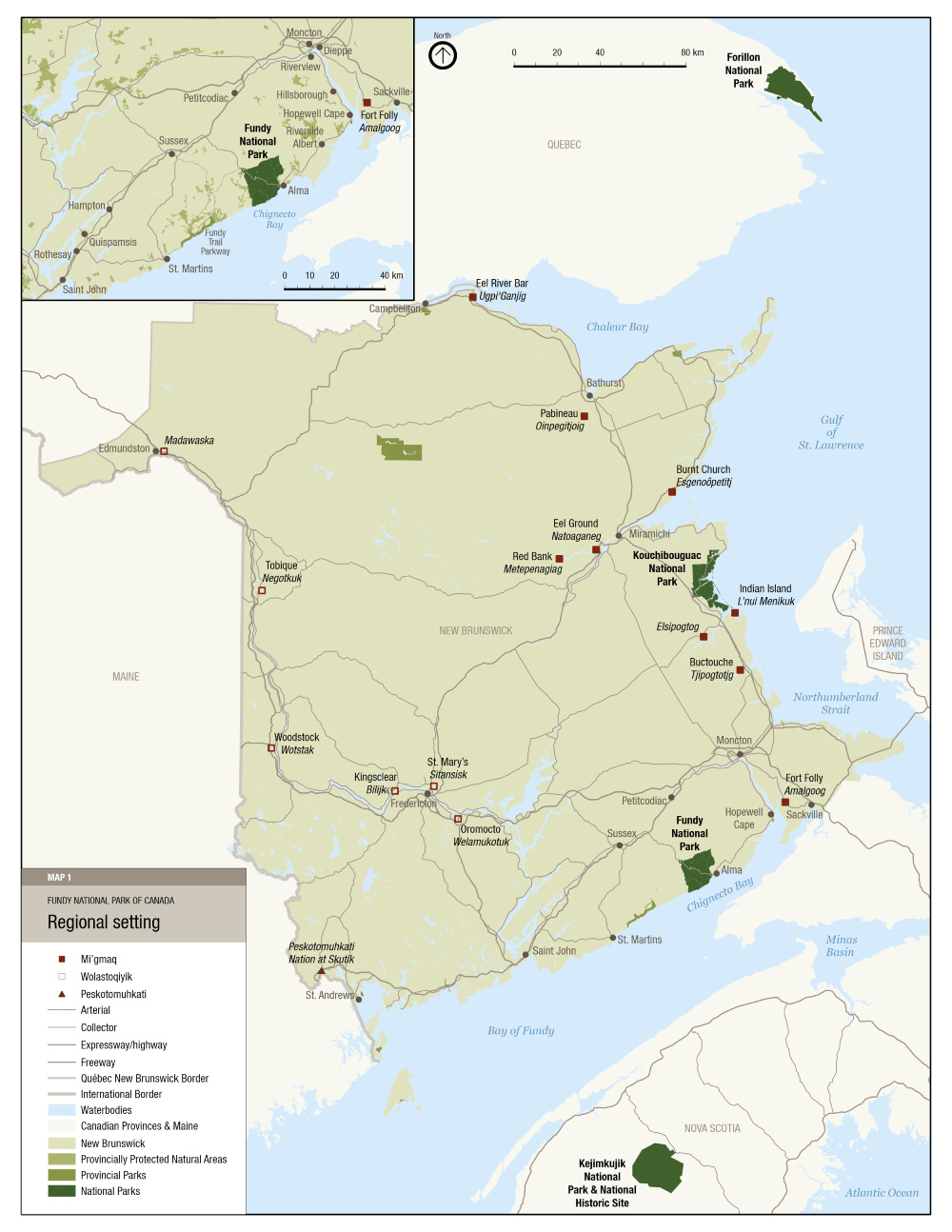

Fundy National Park is located in southern New Brunswick, nestled in the southwest limits of Albert County and bordered on the south by the Chignecto Bay in the Upper Bay of Fundy. The surrounding area is sparsely populated, with the largest nearby community being the newly amalgamated village of Fundy Albert, which includes the former village of Alma. The major population centres of the region include Saint John, Fredericton, and Moncton. Highway 114 bisects the park for 21 kilometres, extending from Wolfe Lake in the northwest to Alma in the southeast, and provides a transportation link to the Trans Canada Highway (Map 1: Regional setting).

Historical context

Fundy National Park is located in the Mi’gmaq district of Signigt’gewa’gi. Often referred to as Siknikt, Signigt’gewa’gi is a Mi’gmaq word which translates to “drainage area” in English, as this was an area with many rivers and waterways that received the meltwaters of the glaciers as they receded northward. Siknikt is the location of a major portage route that linked the Northumberland Strait and Baie Verte with the Bay of Fundy.

Known as L’Nu’g, the Mi’gmaq are the Indigenous people whose traditional territory, Mi’gmaq’i, encompasses the lands and waters of what is currently known as Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, southern and western Newfoundland, the Gaspé area of Quebec, Anticosti Island, the Magdalen Islands, and sections of the Northeastern United States. The rich oral history of the Mi’gmaq affirms the use and occupancy of these lands and waters since time immemorial Footnote 1. The Mi’gmaq have continued to subsist on these lands and waters up to the present day, a testament to the complex social, cultural and political systems of the Mi’gmaq that existed prior to contact Footnote 2. The waterways define the territory, and its districts are outlined by the naturally occurring drainage systems and waterways. As such, Mi’gmaq systems of governance were based at the watershed level Footnote 3.

European exploration of the Bay of Fundy region began in the 16th century, with the Bay of Fundy appearing on Portuguese maps by 1558. Footnote 4 Europeans exploring the Fundy coastline encountered the Mi’gmaq, Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati nations, all members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, who have lived in the region since time immemorial. Gradually, European settlements were established throughout the region, with devastating impacts on First Nations. Within 100 years of the contact period, European diseases accounted for a 75% decline of the First Nations populations Footnote 5. By the latter half of the 19th century, many of the region’s First Nations were living on small parcels of “reserve” land, which often had few resources.

The waterways of the Bay of Fundy, including the Chignecto Isthmus have been a vital transportation corridor for Wabanaki people since time immemorial. European settlement in the surrounding area began in the 1600s with the establishment of the Acadian village of Chipoudie (Shepody) in 1698, approximately 30 kilometres east of the park boundaries.

Map 1: Regional setting

Map 1: Regional setting — Text version

This map shows the location of Fundy National Park within the province of New Brunswick and in proximity to the provinces of Nova Scotia and Quebec, and the state of Maine in the United States of America. In the upper left corner, there is an inset map showing Fundy National Park in the southern region of New Brunswick, the Chignecto Bay area and the western portion of Nova Scotia. There is a 0 to 40km scale in the inset map.

There is a legend in the bottom left corner of the map. The map includes other national parks, Forillon National Park, Kouchibouguac National Park, and Kejimkujik National Park and Historic Site. Mi’gmaq, Wolastoqiyik, and Peskotomuhkati communities are shown on the map including: Eel River Bar (Ugpi’Ganjig), Pabineau (Oinpegitjoig), Burnt Church (Esgenoôpetitj), Eel Ground (Natoaganeg), Tobique (Negotkuk), Red Bank (Metepenagiag), Indian Island (L’nui Menikuk), Elsipogtog, Buctouche (Tjipogtotjg), Woodstock (Wotstak), Kingsclear (Bilijk), St. Mary’s (Sitansisk), Oromocto (Welamukotuk), Fort Folly (Amalgoog), Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik.

The map also shows local communities near Fundy National Park, along the Bay of Fundy, including St. Martins, Alma, Hopewell Cape and Sackville. The cities of Fredericton, Saint John, and Moncton are also shown.

By 1755, approximately 3,000 Acadians were living in the Chignecto Bay area, with about 600 living at Chipoudie. Footnote 6 The Acadians enjoyed a close relationship with the Wabanaki Nations.

The Mi’gmaq, Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati entered into a Covenant Chain of Peace and Friendship Treaties with the British Crown, starting in 1725. These Treaties were not land cession treaties, but protected Wabanaki rights, and were intended to create a mutually beneficial relationship rooted in friendship and trade. These Treaties are still in force and are protected under section 35 of the Canadian Constitution.

During Le Grand Dérangement beginning in 1755, the Acadian villages of the Chignecto Bay region were burned and many inhabitants forcibly removed by British forces. New European settlers of primarily Pennsylvania-German origin began to arrive in the surrounding area in 1766, followed by English, Scottish, and Irish settlers. The first Euro-Canadian settlements within the present-day national park began in the early 19th century. Early settlements tended to cluster around river mouths close to logging-related work, transportation, shipbuilding, and fishing in Chignecto Bay. Remnants of homesteads, roads, cemeteries, schools, bridges, and industry-related structures such as dams, wharves, and mills are found throughout the park, associated with past communities such as Point Wolfe, Alma West, Hastings, and Herring Cove. European settlement and industrial activity had the effect of displacing Mi’gmaq from this area.

Landscape impacts

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, industrial uses such as logging had a profound impact on the landscape with as much as 70% of the forest being cut, and lakes and riverbeds modified for log-driving and water-powered mills. In 1948, the lands were expropriated for the creation of the national park, which officially opened to the public in 1950.

The biophysical context and park boundaries contribute to the importance of Fundy National Park as a core area of the Fundy Biosphere Region. Freshwater rivers, streams and lakes occupy only a small portion of the park landscape yet are critical to the healthy functioning of the park. The park protects only a portion of each of two main river systems, the Upper Salmon and Point Wolfe river watersheds. The remainder of each upper watershed is embedded in an industrial forestry landscape outside of the park.

Current context

As a key tourism destination in southern New Brunswick, Fundy National Park welcomes over 300,000 visitors per year to enjoy spectacular ocean views and landscapes, camping, hiking, biking, and other outdoor recreation. The community of Alma supports a vibrant fishing industry which complements the national park experience with the daily activities of a working wharf within walking distance of the park entrance. Visitors can also experience a variety of sites, local shops and services in Alma while enjoying the national park (Map 2: Local setting).

Parks Canada and Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn Incorporated, signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 2016 establishing the MTI/PC Advisory Committee table. Parks Canada, MTI, and Kopit Lodge (Elsipogtog) have also been working to negotiate a Rights Implementation Agreement that will enable shared stewardship of the national park. Parks Canada and the Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick continue to form collaborative and positive relationships. The management plan has been prepared in consultation with Indigenous partners in the spirit of our Treaty relationship and in spirit of Rights Implementation Agreement(s).

Map 2: Local setting

Map 2: Local setting — Text version

This map shows Fundy National Park and the location of trails, watercourses, roads, waterbodies and provincially protected natural areas. In the lower left corner, there is an inset map that shows the east gate entrance to Fundy National Park, the Upper Salmon River and community of Alma. The map scale of the inset is 0 to 400 metres and the scale of the main map is 0 to 4 kilometres.

There is a legend in the bottom right corner of the map. The provincially protected areas include Mount Tom, McManus Hill, Point Wolfe River Gorge, and Upper Salmon River. Trails are not labelled, but the rivers and water bodies include: Wolfe Lake, Tracey Lake, Laverty Lake, Broad River, Forty Five River, Bennett Lake, Upper Salmon River, Marven Lake, Chambers Lake, Point Wolfe River, Chignecto Lake and Bay of Fundy.

The 2011 management plan provided management direction for maintaining and improving ecological integrity, the recovery of species at risk, increasing visitation through diversified marketing strategies and visitor offers, and engaging with Indigenous partners through collaborative work. Since 2011, Fundy National Park continues to collaborate with Mi’gmaq and Wolastoqey Nations including with the Mi’gmaq through the MTI/Parks Canada Advisory Committee table which meets at regular intervals. Considerable progress has also been made with partners in active management and recovery of species at risk, notably improving the ecological integrity of the aquatic ecosystem which have shown five-year trends in increasing numbers of salmon and establishing Parks Canada’s first research chair in the Atlantic region. Fort Folly Habitat Recovery has been integral in salmon restoration and sharing Mi’gmaq knowledge in a scientific and holistic approach.

Visitation has increased with diversified visitor offers in the fall, winter and spring seasons, through major infrastructure investments such as those in the Chignecto Recreation Area trails and facilities. Major infrastructure investments have also focused on highways and buildings such as the new Visitor Centre at Wolfe Lake, Salt and Fir Centre, and maintenance compound. Other major investments focused on the park’s signature saltwater pool and the addition of new camping areas at Lakeview and Cannontown.

A 2020 State of the Park Assessment reconfirmed the general direction from the 2011 plan with continued focus on active management to increase the sustainability of all park operations, maintaining and improving ecological integrity, improving relationships and collaborations with Indigenous nations, and increasing knowledge of cultural resources.

Climate change presents challenges in the management of ecological impacts to certain species like Atlantic salmon, among others. Restoration programs, such as the Atlantic salmon recovery project, respond to these challenges by increasing the population, and building resilience and adaptability to change. As climate change impacts become increasingly evident, collaborative and adaptive strategies will be important to support natural resource management. More frequent and severe storms will continue to expose the vulnerability of natural and cultural resources, and infrastructure in the park, with increasing damage and costs. Understanding the extent of climate change impacts and taking action toward climate change mitigation and adaptation are an area of focus for park management.

For its size, Fundy National Park maintains one of the largest inventories of assets and operations in Canadian National Parks, and since 2021, operates a year-round visitor offer. For the intent of this plan, “operational sustainability” refers to the long-term, high-quality delivery of the Parks Canada mandate using existing resources. Considering that Fundy National Park is operating year-round within a changing climate and rising operating costs, work is continually required to assess the priority and future viability of all operations and infrastructure. Actions to increase the sustainability of core mandate operations are critical to improve the quality of service, value, and experience for all visitors and will include modernizing or upgrading some operations and decommissioning or scaling down others. Sustainable operations are essential to advance cooperative management with Indigenous partners, protect park ecosystems, ensure the well-being of staff, the enjoyment of visitors and the success of the local economy. Most importantly, sustainable park operations are key to fully realizing the objectives presented in this management plan over the next decade.

4.0 Development of the management plan

This management plan has been developed through an extensive engagement process with MTI, Kopit Lodge and Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick, partners, stakeholders and the public. Discussions and feedback strengthened the management direction in the plan which is reflected in the vision, key strategies, objectives and targets.

During the first phase of engagement in 2021, a management planning newsletter summarizing the proposed vision and priority issues was posted on the park website and circulated to Indigenous partners and key stakeholders with notifications sent to elected officials. Meetings were held with MTI, Kopit Lodge and Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick early in the planning process for the development of the state of park report and the scoping phase. Additional meetings with Indigenous partners were held to discuss the priority issues and opportunities. Conservation and tourism stakeholders, along with municipal, provincial and community organizations, also participated in meetings with park managers to discuss the future of the park and the management planning priorities.

Consultation on the draft management plan during the second phase of engagement included meetings with Indigenous partners and key stakeholder groups. An online comment form with descriptions of the proposed vision and key strategies provided an opportunity to gauge support for the direction in the draft plan and receive specific feedback and opinions. More than 490 respondents participated in the online comment form, providing valuable feedback which was considered and incorporated in the final plan.

5.0 Vision

The natural beauty of the Upper Bay of Fundy, its awe-inspiring tides and pristine coastline nestled against an expanse of Wabanaki (Acadian) Forest, provides an enduring backdrop for exploring and connecting with nature and culture at Fundy National Park. Despite its history of logging, mining and farming, Fundy remains one of the largest tracts of natural coastline from the Bay of Fundy to Florida. Strong collaboration between Indigenous partners, local communities and businesses and the national park supports rural economies and year-round tourism experiences.

Building on this foundation, and all through a lens of sustainable operations, the vision for the next 15 years includes focused efforts on creating a more inclusive, accessible, and diverse experience for park visitors; supporting biodiversity in a changing climate and protecting species at risk; learning more about the impacts of climate change on all facets of park operations and taking action to mitigate and adapt; furthering the role of the park within regional landscapes; and growing relationships with Indigenous communities. Managing these efforts within the existing capacity of the park will improve the overall quality of assets and services benefiting future generations of visitors, staff and partners.

Fundy National Park follows recommendations set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a guideline to address rights and reconciliation. Indigenous culture will be increasingly present in Fundy National Park with cooperative management Footnote 7 providing a structure for shared decision making, mutual learning and respect. Working together toward Etuaptmumk, a “Two Eyed Seeing” understanding, supports Indigenous and western perspectives in identifying and achieving objectives aimed at conservation, ecological integrity, visitor experience and cultural heritage. As the cooperative management relationship grows and strengthens, so too will Canadians’ and visitors’ appreciation and understanding of Indigenous peoples with opportunities to experience language, culture and history through Indigenous-led programming, special events and outreach education.

As a core area of the UNESCO Fundy Biosphere Region, Fundy National Park will strengthen its collaboration with industry and regional conservation partners improving ecological connectivity and protection of significant conservation areas including adjacent coastal environments.

6.0 Key strategies

In this section

- Key strategy 1: Grow together, learn together

- Key strategy 2: Working together to improve ecological integrity and connectivity

- Key strategy 3: Climate resilient and sustainable operations support the delivery of the core mandate and the character of Fundy National Park

- Key strategy 4: Authentic, sustainable, memory-making experiences

Four key strategies frame the management direction for Fundy National Park. The strategies and corresponding objectives and targets focus on the long-term vision for the park through an integrated and sustainable approach to park management. Engagement with Indigenous partners will be a cornerstone of successful plan implementation and the evolving cooperative management relationship. Targets have been prioritized with specific dates where feasible. Where no dates have been referenced, the target will be achieved within the ten-year period of the plan based on opportunities, annual priorities and financial capacity of the national park and Indigenous partners. Annual implementation updates will be communicated to Indigenous partners, local communities, stakeholders, and the public.

Key strategy 1

Grow together, learn together

Fundy National Park is committed to be a place where truth and reconciliation are the foundation of the relationship with Indigenous partners. Growing and learning together in the protection and presentation of the natural and cultural values of Fundy National Park will build the way forward, leading to a strong cooperative management relationship guided by the Treaty principles of peace and friendship, collaboration and respect. The intent of this strategy is to move toward cooperative management of Fundy National Park while at the same time learning more about the cultural use and history of the Fundy region with a focus on weaving Indigenous languages, cultures, history, priorities, rights and interests into park operations. In collaboration with Indigenous partners and community stakeholders, a better understanding of Indigenous and Euro-Canadian history will be developed through a cultural resource values statement which will identify the park’s cultural value in the review of the past and current significance of the location.

Objective 1.1

The principles and foundations of cooperative management of Fundy National Park are established in accordance with Rights Reconciliation Agreement(s).

Target

- Organizational structures are in place and functioning to support cooperative management of Fundy National Park between the Mi’gmaq Nations in New Brunswick and Parks Canada by 2034

Objective 1.2

Knowledge of culture and history improves, contributing to sustainable conservation of cultural resources in Fundy National Park.

Targets

- Indigenous Knowledge Studies designed and developed by Indigenous partners provides information on the cultural history in and around the park

- The inventory of landscape features, archaeological resources and culturally important sites progresses throughout the planning period, resulting in condition ratings in the next state of park assessment

- A cultural resources values statement, developed in collaboration with Indigenous partners and community stakeholders, is complete by 2028

- Collaborative archaeology processes contribute to the condition assessment of cultural resources in the next state of park assessment

Objective 1.3

Wabanaki languages are increasingly present and visible in Fundy National Park operations.

Targets

- The extent of Indigenous languages, place names and interpretation in Fundy National Park increases compared to the 2023–2024 baseline

- Indigenous cultures and languages are integrated into employee orientation and delivered by Indigenous people

Objective 1.4

Indigenous staffing increases in the Parks Canada Field Unit that supports Fundy National Park.

Targets

- Through growing networks of Indigenous collaborators, the recruitment of Indigenous employees in the New Brunswick South Field Unit increases from 2024 levels

- Participation in training and/or orientation opportunities shows an increasing trend at Fundy National Park, supporting recruitment and retention of Indigenous employees

Key strategy 2

Working together to improve ecological integrity and connectivity

The intent of this strategy is to advance priority monitoring and active management within the park and to establish more collaborations with partners outside of the park toward improved ecological connectivity in the broader landscape. The principles of Two-Eyed Seeing, which considers Indigenous and western knowledge as we work toward monitoring and maintaining ecological integrity, will be a focus in a cooperative management relationship. Inside the park, monitoring will include Indigenous knowledge guiding decisions for active management with a focus on at-risk and culturally important species. Managing the operational footprint, understanding the effects of climate change on ecological processes, and implementing approaches for climate change adaptation will also be a priority. Continued participation in regional climate change initiatives and academic collaborations will also advance the understanding of potential impacts on the natural and cultural resources in the park and inform mitigation and adaptation actions.

As a protected area, Fundy National Park acts as a core natural area in a diverse landscape consisting of human development, agricultural lands and industrial forests. Outside the park, Fundy is known as a hub of leadership and expertise for regional freshwater ecosystem and salmon restoration. Ecological connectivity will be supported by developing strategic partnerships, sharing information and collaboration thereby improving ecological connectivity within the UNESCO Fundy Biosphere Region.

Objective 2.1

Ecological monitoring based on Etuaptmumk (a Two-Eyed Seeing approach), involving both Indigenous knowledge and western science, assesses and reports on ecological integrity, and guides active management.

Targets

- Ecological integrity measures are reviewed and adjusted in collaboration with Indigenous partners by 2029 in the next state of park assessment

- Climate-driven impacts on ecological systems are reported in the ecological monitoring program prior to the next management plan review

Objective 2.2

Biodiversity, including priority species at risk and species of cultural importance, is prioritized for protection and recovery.

Targets

- With sustained Two-Eyed Seeing restoration actions, salmon populations continue an improving trend resulting in “fair” condition in the next state of park assessment

- By 2034, the primary productivity of the freshwater ecosystem trends upward or stable over 2015 levels, because of active salmon restoration

- Indigenous knowledge and guidance influence monitoring and conservation initiatives on species of cultural importance such as salmon, eel, trout, and moose

- Fundy’s new multispecies action plan is developed by 2025 considering landscape connectivity, known climate change trends and projections, culturally important species, and including priority recovery actions beyond park boundaries

Objective 2.3

Ecological connectivity is protected by collaborating with Indigenous partners and other partners to prioritize restoration of connectivity within the park and support collaborative efforts to create and protect ecological corridors around the park.

Targets

- Fundy National Park has established an active working group with Indigenous partners and regional partners to protect and/or improve ecological connectivity by 2029

- Ecological corridors within Fundy National Park are protected and effective remediation and restoration has started in 2034, based on baseline levels from 2024

Objective 2.4

Evidence-based models contribute to prioritizing restoration efforts and managing the disturbed area footprint within the park and are utilized to support future proposals for infrastructure and/or services.

Targets

- A prioritized restoration plan for Fundy National Park with identified costs will guide restoration actions by 2029

- By 2034, the restoration plan will be in implementation phase and restoration will be underway according to priority

Key strategy 3

Climate resilient and sustainable operations support the delivery of the core mandate and the character of Fundy National Park

Fundy National Park has an extensive inventory of assets which are original and beyond functional lifespans. To deliver Parks Canada’s core mandate with quality services and experiences for families, campers and hikers, and other target markets, over the next ten years and beyond, a focus on realistic maintenance capacity within existing resources is critical. Strategic assessment of the long-term viability of park operations is required. In some cases, reduction of the quantity of services offered will be required to maintain the highest possible levels of quality, value, and sustainability for the future. This will include understanding the priorities and interests of Indigenous partners and visitors to identify a range of management options. Facilities and services will be evaluated through a climate-smart lens, with the goal of investing in resilient infrastructure and removing vulnerable components. Aligning operational requirements with available resources is a key focus of this strategy.

Objective 3.1

Operational sustainability is improved through the assessment of composition, condition, cost and revenue generation capability of the asset portfolio, and core mandate priorities.

Targets

- Point Wolfe electrical and water systems assessment is completed by 2025

- Asset consolidation is considered, where feasible, with design work for a multi-purpose space prepared by 2025

- Recreational assets are reviewed by 2028 in view of adapting to modern activities and interests which align with the Parks Canada mandate

- The condition of park infrastructure is assessed, and management options for optimizing the size and composition of the asset portfolio are identified or in action by 2034

- Assets that are underutilized, not critical for core program purposes, or redundant, are identified for rationalization and/or divestment by 2034

- Infrastructure projects and proposals that may impact cultural resources, incorporate meaningful collaboration with Indigenous partners

- The condition of buildings improves to “fair” to “good” in the next state of park assessment

Objective 3.2

Green procurement results in improved energy efficiency for park operations.

Targets

- Zero-emission vehicles will be prioritized when replacing light duty vehicles, where feasible, in alignment with Parks Canada’s objective

- Greenhouse gas emissions are reduced through the retrofitting of inefficient heating systems and/or replacement of fuel oil heating sources with greener alternatives by 2030

Key strategy 4

Authentic, sustainable, memory-making experiences

Fundy National Park experiences high visitation during its year-round operations which supports regional economic development in cooperation with partners and the tourism industry. Visitation in the fall, winter, and spring has grown since the addition of roofed accommodations in 2014. With rising operating costs, an extensive asset portfolio, and a desire to continue to provide high-quality experiences, there is a need to focus on the priorities of park users. A fully accessible visitor experience, from planning to arrival to departure, will be prioritized in this key strategy along with a focus on a sustainable trail network. Protection of ecological integrity will guide visitor use management approaches for high-visitor use areas.

Objective 4.1

Visitors experience renewed offers and have a variety of inclusive, accessible options for enjoying facilities and services at Fundy National Park.

Targets

- An accessibility evaluation of facilities identifying key items in the headquarters area will be addressed, and appropriate changes implemented to remove barriers by 2029

- Visitor satisfaction with facilities in Fundy National Park is maintained at over 85% satisfied or very satisfied in the next state of park assessment

Objective 4.2

Visitors continue to have opportunities to experience sustainable year-round offers and services in Fundy National Park.

Targets

- A baseline for visitor satisfaction during the winter will be established

- Weekend occupancy of available winter accommodations is maintained at over 80%

- Partnerships or mutual agreements with Indigenous tourism operators and other regional destinations are established, offering more complete fall, winter and spring season visitation experiences

Objective 4.3

Individuals, groups, partners, and communities are increasingly engaged in programing and seasonal activities at Fundy National Park.

Targets

- Increased opportunities for Indigenous families and youth to visit the park through direct engagement with community leaders, and the development of more Indigenous interpretation and programming are in place by 2029

- Land-based learning, connecting with Elders, Fire Circle, and other Indigenous-led programing are in place by 2034

- Engagement in delivering park programming shows an improving trend in the next state of park assessment

Objective 4.4

Visitor experience and ecological protection improves in high-visitation areas of Fundy National Park through visitor use management strategies to ensure visitation levels are sustainable.

Targets

- Visitor use management plans are completed for Dickson Falls, Laverty Falls, and Point Wolfe Trailhead by 2030

- The proportion of overnight stays from September to October increases from the 2024 baseline, within overnight park capacity limits

- A new protocol for counting visitation which includes measuring winter and spring visitation will be developed and implemented by 2026

Objective 4.5

An enhanced trail network focusing on quality over quantity improves conditions for visitors.

Targets

- A trail assessment, taking climate change risks (for example, rise in ocean elevation) into consideration, guides the restoration, decommissioning and building of new trails by 2029

- Visitors report increased satisfaction with trail condition in the next state of park assessment

- Promotion of the backcountry trail network in Fundy National Park, and partner trail networks improves within Fundy National Park, and externally through online communication tools, and in-person promotional events

7.0 Zoning and declared wilderness area

In this section

7.1 Zoning

Parks Canada’s national park zoning system is an integrated approach to the classification of land and water areas in a national park and designates where particular activities can occur on land or water based on the ability to support those uses. The zoning system has five categories:

- Zone I: Special Preservation

- Zone II: Wilderness

- Zone III: Natural Environment

- Zone IV: Outdoor Recreation

- Zone V: Park Services

The Zoning map (Map 3) illustrates the zone designations and environmentally sensitive areas in Fundy National Park.

The amendments from the 2011 management plan are further described below and include:

- a new Zone I Area to protect rare saltmarsh plant species

- two environmentally sensitive areas to protect species and habitats in Maple Grove and Devil’s Half Acre

- a change from Zone III to Zone II for the coastal area south of Point Wolfe Road

- a change from Zone IV to Zone III for the Chignecto Recreation Area

The zoning amendments support the direction in key strategy 2 with respect to increasing the protection of biodiversity and ecological connectivity. An increased area of Zone II wilderness ensures that only minimal visitor use will be considered in this area with no motorized access, infrastructure or facilities. Likewise, the re-zoning of the Chignecto Recreation Area supports the transition from a fully serviced campsite to a less intensive visitor use area with no motorized access and the rehabilitation of roads and areas previously occupied by infrastructure.

The overall proposed changes of each zone in the park, from the 2011 management plan are:

- Zone I: 1.58% to 1.59%

- Zone II: 88% to 91%

- Zone III: 6% to 3%

- Zone IV: 4% to 3.9%

Zone I Special Preservation

Zone I areas provide the highest level of protection offered by Parks Canada’s Zoning Policy. Specific areas or features under this zoning deserve special preservation because they contain or support unique, threatened, or endangered natural or cultural features or values, or are among the best examples of a natural region. Preservation is the key consideration. Motorized access and circulation are not permitted, and visitor access is not encouraged in order to protect these features. Special features may be interpreted off-site.

There are six areas within Fundy National Park that are categorized as Zone I Special Preservation. These areas cover approximately 1.5% of the park and include: Point Wolfe Coastal Cliffs; Goose River Coastal Cliffs; Rossiter Brook Valley; Caribou Plain; Point Wolfe River / Bennett Brook Ravines; and an area at the mouth of the Upper Salmon River.

Point Wolfe Coastal Cliffs: contain one of two known New Brunswick sites of the bird’s-eye primrose, a small herbaceous plant of northern affinity. This area is also one of the best potential nesting locations in the park for the Peregrine Falcon, formerly a species at risk, now recovered through the conservation actions of Parks Canada and its partners. The best examples of the inner Bay of Fundy soft rock (sandstone and conglomerate) coastal cliffs are also located in this zone.

Goose River Coastal Cliffs: contain the second of two known New Brunswick sites of the bird’s-eye primrose. Along this rugged, precipitous coast there are also potential Peregrine Falcon nesting sites.

Rossiter Brook Valley: contains stands of rare old red spruce trees.

Caribou Plain: contains excellent examples of black spruce and raised-bog vegetation types, which are very rare in the park and surrounding region. These habitats are sensitive to visitor disturbance.

Point Wolfe River and Bennett Brook Ravines: the east branch of the Point Wolfe River and the lower part of Bennett Brook are the only locations in the park where the following rare flora are known to occur: slender spikemoss, squashberry, green spleenwort, a rare sedge species, and fir clubmoss. This area also contains some of the best examples of critical habitat for the endangered Atlantic salmon (inner Bay of Fundy), including some of the largest salmon pools on the Point Wolfe River.

Zone I amendments

A new Zone I Area, south of the mouth of the Upper Salmon River, protects the Roland’s sea-blite plant which was discovered growing in Fundy National Park in 2016. This provincially, nationally, and globally rare saltmarsh species is only known from a handful of sites in northeastern North America. Annual monitoring will contribute to better understanding the dynamics of plant establishment and movement.

Zone II Wilderness

The purpose of the Zone II designation is to provide a high level of protection for large areas that well represent a natural region and that will be conserved in a wilderness state. Perpetuation of ecosystems with minimal management intervention is encouraged. Visitors experience the remoteness of such zones in ways that are compatible with maintaining the wilderness character such as hiking and backcountry camping. Motorized access and circulation within this zone are not permitted and infrastructure is restricted to rudimentary facilities such as hiking trails and backcountry campsites. There are seven areas that are within Zone II, comprising more than 90% of the park.

These Zone II areas include:

- Upper Salmon Valley

- Point Wolfe River Valley

- Tracey Lake Wilderness Campsite

- Goose River Wilderness Campsite

- Marven Lake Wilderness Campsite

- Chambers Lake Wilderness Campsite

- McKinley Cabin

Zone II amendments

The coastal area south of Point Wolfe Road to Matthews Head has changed from Zone III to Zone II to increase the conservation and protection in this area of the national park. This increases Zone II area of the park from 88 to 91%.

Zone III Natural Environment

Zone III designations are applied to areas that are managed as natural environments and that provide opportunities for visitors to experience a park’s natural and cultural heritage values through outdoor recreation activities requiring minimal services and facilities of a rustic nature. These areas can sustain a range of outdoor activities, which are compatible with preserving natural settings, including swimming, canoeing, hiking, biking, picnicking, non-motorized boating, snowshoeing, skiing and on-site interpretation. While motorized access may be allowed, it is controlled.

There are two areas within Fundy National Park that are within the Zone III that cover approximately 3% of the park. These areas include:

- the small area of Bennett Lake

- land bounded by Point Wolfe Road, Hastings Road and Highway 114 (excluding the Zone IV designations)

Zone III amendments

The Chignecto Recreation Area changes from Zone IV to Zone III as motorized access is no longer permitted. In Zone III, controlled motorized access may be permitted. The parking lot remains in Zone IV and roads will be rehabilitated to trails. Group camping may be a future use in this area.

The Point Wolfe to Matthews Head area changes from Zone III to Zone II to increase conservation and protection in this area of the park.

Zone IV Outdoor Recreation

This designation is given to limited areas that can accommodate a broad range of opportunities for understanding, appreciating and enjoying the park’s heritage values and related essential park services and facilities, in ways that impact the natural and cultural resources of the park to the smallest extent possible. Direct access by motorized vehicles is permitted. Landscaping activities in Zone IV areas will place a greater emphasis on utilizing native species and restoring natural habitats where feasible.

There are eight main Zone IV areas within the park that cover approximately 4% of the park.

These general areas include:

- headquarters area, maintenance facilities and pumphouse

- day-use areas

- campgrounds

- Fundy Motel / Chalets

- Highway 114

- saltwater Pool

- golf course

- all park roads

Zone IV amendments

Two areas of Zone IV have been reduced to accommodate the new proposed Zone III at the Chignecto Recreation Area and the new proposed Zone I to protect Rolland’s sea-blite. The total area of Zone IV has changed to just under 4%.

Environmentally sensitive sites/areas

Areas which contain resources that are unique, rare, or especially vulnerable to disturbance but which are too small to be considered for designation as a Zone I Area are classified as environmentally sensitive sites. These sites receive a high degree of protection through careful management. Designation as an environmentally sensitive site ensures that the unique values of these sites are considered in future planning, research, and development activities.

The environmentally sensitive sites are described in Appendix 1. The criteria used in identifying these sites include:

- natural features or habitat of species that are rare nationally, regionally, or locally

- fragile ecosystem components that are sensitive to visitor use and/or development

- habitat that is essential to a species for specific periods of its life cycle, such as denning, spawning, breeding, and overwintering areas

Amendments

Two environmentally sensitive areas have been added as overlays on the zoning map to increase the protection for sensitive species and habitats.

Rare lichen habitat — Mature hardwoods Maple Grove–Tippen Lot: the mature hardwood forest habitat of the Maple Grove / Tippen Lot North area harbours lichens that are both provincially and nationally rare. Scaly fringe lichen is found there and is newly designated as “Threatened” by COSEWIC Footnote 8 (December 2022). Fundy National Park is the only Parks Canada site in which it is known to occur. Appalachian speckleback lichen also inhabits this area and is critically imperilled in the province, and vulnerable at the national level.

Devil’s Half Acre critical bat habitat: the topography and rock formations of the Devil’s Half Acre area lend themselves to the formations of deep fissures and caverns, which have housed colonies of little brown myotis in the past. Although no currently known hibernacula exist there, this area was designated critical habitat in the recent “Recovery Strategy for the Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus), the Northern Myotis (Myotis septentrionalis), and the Tri-colored Bat (Perimyotis subflavus) in Canada.”

Non-conforming uses

Some zones support uses or activities that do not conform to the spirit and intentions of the zone type. Non-conforming uses in Zone II include cell towers, the Wolfe Lake Dam and access road, hydropower transmission corridor, the pumphouse and access road adjacent to the Salmon River. The sewage lagoon is a non-conforming use in Zone III.

7.2 Wilderness area declaration

The intent of legally designating a portion of a national park as wilderness is to maintain its wilderness character in perpetuity. Only activities that are unlikely to impair the wilderness character of the area may be authorized within the declared wilderness area of Fundy National Park.

A wilderness area was formally established in Fundy National Park in 2009. In general, the declared wilderness area boundaries follow Zone II Wilderness boundaries. In addition, where Zone I Special Preservation areas are included in or are adjacent to Zone II areas or are large enough to be considered on their own, they may be included in declared wilderness areas. This is the case for Fundy National Park where Zones I and II make up the Declared Wilderness Area for the park and cover approximately 89% of the national park land base.

Map 3: Zoning map

Map 3: Zoning map — text version

This map shows the four zones within Fundy National Park. There is a legend in the bottom right corner and the scale of the map is 0 to 2 km.

There are six zone I special preservation areas shown in green including Point Wolfe Coastal Cliffs, Goose River Coastal Cliffs, Rossiter Brook Valley, Caribou Plain and Point Wolfe River.

Zone II Wilderness is shown on most of the national park in a light brown shading. The Declared Wilderness Area overlaps with most of zone II, with the exception of the land between Point Wolfe Road and Herring Cove Road.

Zone III Natural Environment, is shown in a yellow colour in an area bound by Highway 114, Hastings Road and Point Wolfe Road.

Zone IV Outdoor Recreation, is shown in dark brown, and includes the roads in the national park, the campground and administrative area near the east entrance.

8.0 Summary of strategic environmental assessment

All national park management plans are assessed through a strategic environmental assessment to understand the potential for cumulative effects. This understanding contributes to evidence-based decision-making that supports ecological integrity being maintained or restored over the life of the plan. The strategic environmental assessment for the management plan for Fundy National Park considered the potential impacts of climate change, local and regional activities around the park, expected increase in visitation and proposals within the management plan. The strategic environmental assessment analyzed the potential impacts on different aspects of the ecosystem, including Atlantic salmon and terrestrial connectivity.

The management plan will result in many positive impacts on the environment, including continued efforts to recover the Atlantic salmon population; protecting ecological connectivity through collaboration, partnerships and restoration; improving energy efficiency for park operations; development of visitor use management plans to mitigate impacts at high-visitation areas of the park; and zoning amendments to increase conservation and protection of areas within the park.

While many ecological integrity measures in the park are in fair to good condition, some require sustained active management for continued improvement. Atlantic salmon, inner Bay of Fundy population, are an endangered species and numbers of adult salmon returning to the park to spawn are poor. Restoration initiatives have increased numbers of returning salmon, but continued focus on recovery is required to maintain this trend. External development, particularly commercial forestry, impacts riparian habitat, posing a challenge to effective conservation of the species. Climate change and conditions at sea further impact the species. The Atlantic salmon inner Bay of Fundy action plan sets out direction for the park to recover the species. The management plan identifies goals to support continued recovery efforts of Atlantic salmon including improving freshwater ecosystem trends through salmon restoration, informing salmon monitoring and conservation initiatives through Indigenous knowledge and guidance, and understanding the effects of climate change on species within the park.

Fundy National Park has a high trail/square kilometre density, and the trail network bisects large patches of forest. In addition, Highway 114 bisects the park for 21 kilometres. Increased visitation, internal and external infrastructure development and recreational activities result in cumulative effects that contribute to decreased terrestrial connectivity within the park and to neighbouring areas. This impacts wildlife movement and habitat occupancy. A carnivore habitat connectivity study was conducted to assess the quality of connectivity corridors used by wide-ranging carnivores within the park and surrounding lands to inform the strategic environmental assessment. The management plan identifies goals to protect and improve connectivity including the development of an active working group with Indigenous partners and regional partners; development of a new multi-species action plan considering landscape connectivity; and protecting and restoring ecological corridors.

First Nations, partners, stakeholders, and the public were provided with opportunities to provide comments on the draft management plan and summary of the draft strategic environmental assessment. Comments from the public, Indigenous groups, and stakeholders were incorporated into the strategic environmental assessment and management plan as appropriate.

The strategic environmental assessment was conducted in accordance with The Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals (2010) and facilitated an evaluation of how the management plan contributed to the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. Individual projects undertaken to implement management plan objectives at the site will be evaluated to determine if an impact assessment is required under the Impact Assessment Act or successor legislation. The management plan supports the following Federal Sustainable Development Strategy goals, namely:

- foster innovation and green infrastructure in Canada

- take action on climate change and its impacts

- protect and recover species, conserve Canadian biodiversity

Many positive environmental effects are expected, and there are no important negative environmental effects anticipated from implementation of the Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan.

Appendix A Environmentally sensitive sites

Salamander habitat

Hemidactylium scutatum (four-toed salamander): In New Brunswick, this species is known from only one confirmed site in Fundy National Park. Although a park-wide survey in 1999 has confirmed its presence at only one location in the park, potential habitats also exist at several other locations.

Ambystoma laterale (blue-spotted salamander): With a patchy distribution in southern New Brunswick, this species is known from only one location in Fundy National Park.

Desmognathus fuscus (dusky salamander): Fundy National Park is the only national park in Canada in which this species is present, and it is found at only one location within the park.

Rare bryophytes (mosses and liverworts)

Cyrtomnium hymenophylloides: This is a significant bryophyte species in the Gulf of St. Lawrence region. It is an example of an arctic-alpine species, requiring specific habitat conditions. It is found at four locations in Fundy National Park, two of which are protected within Zone I areas. A third site is designated as an environmentally sensitive site because it is vulnerable due to its easily accessible location.

Hygrohypnum montanum: This is a significant bryophyte species, infrequent in the Gulf of St. Lawrence region, and known from only one location in New Brunswick, found in Fundy National Park in 1968.

Radula tenax: The discovery of this liverwort species growing on a humid shaded cliff in Fundy National Park represents the only record of its existence in Canada.

Tetrodontium brownianum: A boreal species of moss with a disjunct distribution in North America, it is found in three sites in the park where it is highly habitat-specific.

Tortella humilis: A moss species considered rare in the Gulf of St. Lawrence region, which is at its northern limit in the park.

Rare vascular plant species

Habernaria hyperborea (leafy green orchid): This species is rare in the park, where it is found in only a few locations.

Sanguisorba canadensis (Canada burnet): This plant is rare in New Brunswick and in the park, where it is found at only two locations.

Atlantic salmon pools and spawning habitat

Salmo salar (Atlantic salmon): The inner Bay of Fundy Atlantic salmon population has been assessed as Endangered by COSEWIC as of May 2001 and is listed as Endangered under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act. In the park, two rivers contain critical habitat for this species.

Salt marsh habitat: Salt marsh vegetation communities are uncommon in the park. Because of the small area of salt marsh habitat in the park, they are important for supporting ecological systems and biodiversity not found in other more common habitats.

Frost pocket heathland plant: Associations and climatic conditions found in the frost pocket heathland are unique in the park and are representative of flora usually found in more northerly climates.

Peltigera hydrothyria (Eastern Waterfan): is an aquatic species of lichen that inhabits cool, clear, relatively undisturbed forested streams. Prior to 2017 it was only known in New Brunswick from three locations (two in Fundy National Park). Recent survey work revealed that Fundy National Park is a stronghold for this rare aquatic lichen, with nearly half of its Canadian population occurring within the boundaries of the park. Originally known to occur in 2 brooks in Fundy, it has since been discovered growing in nearly 30 brooks and counting. Eastern waterfan is listed as Threatened in Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act and critical habitat occurs within the park.

Contact us

For more information about the management plan or about Fundy National Park of Canada:

Fundy National Park of Canada

P.O. Box 1001

Alma NB E4H 1B4

Canada

Publication information

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, represented by the President & Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2024.

Front cover image credit:

top from left to right: Julie Ouellette, Chris Reardon, Nigel Fearon

bottom: Danielle Latendresse

Cette publication est aussi disponible en français :

Plan directeur du parc national Fundy, 2024

- Paper: R64-105/80-2024E

- 978-0-660-69504-4

- R64-105/80-2024E-PDF

- 978-0-660-69503-7

- Date modified :