Executive Summary

The primary mandate of the protection of the public and infrastructure from the negative effects of wildfire are addressed in this plan through clearly defined minimum resourcing levels, preparedness guidelines and wildland fire zoning. Furthermore, fuel management implementation guidelines are focused on maintaining or improving existing fuel management units in the wildland-urban interface and creating landscape level fuel breaks to assist in the safe implementation of prescribed fire in BKY.

Despite restoration efforts over the past 30 years, monitoring indicates that ecosystem health within the parks continues to decline due to previous fire exclusion policies resulting in significant fire cycle deficits. A continued emphasis on fire suppression also continues to heighten socio-economic vulnerability over the long term in the absence of management actions to offset these negative impacts. The PCA wildland fire zoning approach with a focus on a landscape that is tolerant of as many intermediate and extensive zones as possible is a step towards a more fire resilient landscape. In recent years, application of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) has further constrained the application of fire. While land managers understand that natural events such as predation are clearly excluded in the act, the legislation can make it challenging to facilitate natural processes such as fire, floods, and avalanches, as these activities may constitute destruction of critical habitat. However, because these natural forces are often managed (within the natural range of variability) to strategically protect the public and park infrastructure, they must be formally permitted (via a SARA authorization) if we are to retain the very diversity of structure and resulting biodiversity that is so critical for the persistence of many of these species at risk.

Fundamental to the success of Parks Canada’s fire program is a socio-cultural acceptance of fire as a process vital to the maintenance of biological structure, function and diversity. The need to embrace the concept and practice of living with fire while mitigating its impacts is necessary if these trends are to be reversed and our park ecosystems protected. The communications, public engagement and visitor experience section addresses the integrated delivery of the fire program in order to foster the public’s understanding of the important role fire plays in the ecosystems of Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks.

Introduction

Scope and Context

This Integrated Fire Management Plan (IFMP) is a blueprint for fire protection and fire restoration within Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks (BKY). In addition to the national parks, the plan includes the Cave and Basin, Rocky Mountain House and Kootenae House national historic sites as well as the Ya Ha Tinda Ranch.

Management actions are guided by clear strategic guidance, thorough consultation, and established performance measures (see Section 8.0) with a focus on science-based decision making. Preparation of this plan has involved consultation with managers within the Parks Canada Agency (PCA), Indigenous nations, stakeholders and adjacent land managers regarding shared opportunities and challenges, and mutually supportive management strategies.

Legal and Administrative Framework

The following is a general breakdown of the legal and administrative framework that guides wildland fire management activities in the Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks.

Canada National Parks Act

The main principles underlying wildland fire management at Parks Canada are derived primarily from the Canada National Parks Act, which indicates that:

Maintenance or restoration of ecological integrity, through the protection of natural resources and natural processes, shall be the first priority of the Minister when considering all aspects of the management of parks

Ecological Integrity

Section 2 (1) of the Canada National Park Act defines ecological integrity as a “condition that is determined to be characteristic of its natural region and likely to persist, including abiotic components and the composition and abundance of native species and biological communities, rates of change and supporting processes.” The term ecological integrity provides a focus for ecosystem-based management that goes beyond legislated park boundaries to include the cooperation and consultation with a wide variety of internal and external client groups.

The concept recognizes that ecosystems are dynamic and self-organizing entities and what may have been natural in the past may not be the natural state for today. Therefore, a challenge for park managers is to determine the baseline for wildland fire management planning based on the current state of the ecosystem.

Wildland Fire Management Directive

The National Fire Management Directive (Parks Canada, 2017) provides direction on the requirement for demonstrated fire control capabilities prior to phased use of prescribed fire. It emphasizes that a balance must be achieved between ecological, social and economic criteria appropriate for the greater park landscape. Operational safety, air quality, stakeholder concerns, cost, and other variables must all be considered in the fire management planning process.

Specific guidelines for fire management indicated in these documents state:

National park ecosystems will be managed with minimal interference to natural processes. However, active management may be allowed when the structure or function of an ecosystem has been seriously altered and manipulation is the only possible alternative available to restore ecological integrity.

Where manipulation is necessary it will be based on scientific research, use techniques that duplicate natural processes as closely as possible, and will be carefully monitored.

Ecosystem managers and wildland fire managers are expected to add the following to their respective responsibilities:

- Know and understand the role of fire in the development of ecosystems before implementing a fire use program, and

- Reproduce all possible aspects of the fire regime when implementing prescribed burning within a park.

The Wildland Fire Management Directive (Parks Canada, 2017) provides direction on the control and use of vegetation fires in Canada’s national parks and national historic sites. The directive states that all fire management activities in a national park will be detailed in a fire management plan. This plan will be developed in consultation with stakeholders in communities, surrounding jurisdictions, and with fire management specialists. Fire management plans are developed to direct the control and use of fire to achieve specific objectives.

Fire management is defined in the Management Directive as:

- Those activities associated with the protection of people, property, and landscapes from fire, as well as the use of prescribed fire to achieve land management objectives.

The national Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Wildland Fire Management Planning (Parks Canada, draft 2018), when complete, will be used to further guide and support fire management planning at the field unit level. This SOP details the planning requirements and review/approval procedures for fire management plans, prescribed fire plans and wildfire risk reduction plans.

Species at Risk Act

All fire management planning, actions and monitoring must be fully integrated with the legislative requirements of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). Under SARA, the following criteria have been established for all activities including fire that will potentially affect a species at risk listed under Schedule 1 as extirpated, endangered or threatened:

- All reasonable alternatives to the activity must be considered and the best solution must be adopted

- All feasible measures to mitigate the impact of the activity on the species, critical habitat or residences must be identified; and

- It must be demonstrated that the activity will not threaten the survival or recovery of the species.

This fire management plan integrates all regional SARA recovery action plans and their goals as well as the approved multi-species action plans for BKY (Parks Canada, 2017).

The Species at Risk Act (SARA) provides protection for listed species at risk in Canada such as Woodland Caribou, White Bark Pine and other schedule 1 listed species found in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks. The Act provides federal legislation to conserve and protect Canada’s biological diversity. It fulfills a key commitment under the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity. All federal lands, including national parks, came under the regulations and prohibitions of SARA, in June 1, 2004. All wildland fire management planning, wildland fire suppression, prescribed fire operations, fuel management actions and monitoring are subject to SARA prohibitions and species at risk considerations. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for prescribed fire and fuel modification plans will contain applicable SARA authorizations and considerations as outlined by an impact assessment satisfying the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA, 2012).

The only exemption from SARA prohibitions applies to emergency wildland fire suppression with the exception of preplanning for park fire and related vegetation plans. While emergency suppression activities are set aside from SARA, every reasonable action will be made to reduce effects to and accommodate at risk species during suppression activities.

National Park Management Plans

There is a legislative obligation for park management plans to meet ecosystem restoration objectives and a policy requirement to have a current fire management plan to conduct fire-related actions. The park management plan (PMP) ensures a strategic investment of resources to maximize fire’s ecological benefits while minimizing its negative socio-cultural and economic impacts. It also ensures that fire management activities support and strengthen other field unit priorities including species at risk recovery plans, conservation and restoration projects, and Visitor Experience and External Relations initiatives proposed for the same timelines.

Each of the three national park management plans (2010) provide specific goals and objectives regarding fire management include. Tables 1, 2 and 3 outline key goals and objectives from these plans that guide fire management activities within the park

Table 1: Banff Park Management Plan Goals of the Fire Management Program

| PMP Section 5.3.3.8: Where vegetation structure has been restored, use prescribed fire on a repeated basis to maintain grasslands and forest savannas. |

| PMP Section 5.3.3.9: Through prescribed and wildfire, work to ensure that all parts of the park achieve 50% of their long-term fire cycle. |

| PMP Section 5.3.3.1: Collaborate with scientists, interested community members, citizen scientists and park visitors on adaptive management experiments aimed at understanding and restoring key ecological processes (predation, fire, herbivory and dispersal) that sustain Banff’s montane ecosystems. |

Table 2: Yoho Park Management Plan Key Strategies and Actions of the Fire Management Program

| PMP Section 4.1.3 Design and implement conservation measures such as prescribed fires, historic building restoration, salvage archaeology, and trail relocations in ways that provide opportunities for visitors to witness the action and learn about the reasons for undertaking these measures. |

| PMP Section 4.4.1 Develop partnering arrangements with the Town of Golden and other communities in the Columbia Valley that enhance mountain park outreach and education around restoration and conservation projects, including fire ecology, aquatic health, species at risk, and highway wildlife mitigation. |

| PMP Section 4.6.1 Restore fire to the landscape by using prescribed fires and carefully managed natural fires to achieve 50% of the long-term fire cycle and restore natural vegetation characteristics in all ecosystems, as detailed in the field unit fire management plan. |

| PMP Section 4.6.2 Maintain large, natural landscapes that support healthy grizzly bear populations and provide opportunities for wilderness recreation. |

Table 3: Kootenay Park Management Plan Key Strategies and Action of the Fire Management Program

| PMP Section 4.1.3 Design and implement conservation measures such as prescribed fires, historic building restoration, salvage archaeology, and trail relocations in ways that provide opportunities for visitors to witness the action and learn about the reasons for undertaking these measures. |

| PMP Section 4.2.2 Use the historic and continuing presence of fire and forest regeneration along the length of the park as a way of differentiating Kootenay from other mountain parks. |

| PMP Section 4.4.1 Develop partnering arrangements with the Village of Radium Hot Springs and other communities in the Columbia Valley that enhance mountain park outreach and education around restoration and conservation projects, including fire ecology, Redstreak restoration, aquatic health, species at risk, and Highway 93 South wildlife mitigation efforts. |

PMP Section 4.6.1

|

| PMP Section 4.6.3 Develop and periodically update communication products as fire and forest patterns change, to build awareness and understanding of fire and vegetation dynamics. |

| PMP Section 5.1.3 Use prescribed fire to restore open meadow communities in the Kootenay River valley. |

| PMP Section 5.3.4 Complete remaining priority actions of the Redstreak Restoration Project, including the removal of remaining infrastructure on the west side of the highway and on the Redstreak Bench, and the completion of forest thinning and prescribed burning. Conduct low intensity prescribed fires to maintain the open forest-grassland ecosystem. |

Site Description

Geographic Context

Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks, in conjunction with Jasper National Park, form a network of protected areas which are contiguous with three B.C. provincial parks (Mount Robson, Mount Assiniboine, Hamber and Height of the Rockies provincial parks). These contiguous protected areas combine to form the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site designated under the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1983. Additionally, the 2.3 million contiguous hectares adjoin three provincial ecological reserves (Wilmore, Ghost, Siffleur) and several other provincial parks (Spray Lakes, Peter Lougheed, Bow Valley, Elbow-Sheep River, Height of the Rockies, Kakwa, Elk Lakes, Top of the World) in both British Columbia and Alberta, adding another 500,000 hectares. Collectively, the 28,000 square kilometres form one of the largest contiguous terrestrial protected areas in North America, a landscape that depends on fire as the principal driver of biodiversity and ecosystem health.

These three national parks straddle the Continental Divide along the Rocky Mountain range, with Kootenay and Yoho to the west and Banff to the east (Figure 1). This range is characterized by thrust-faulted ridges that generally form a southeast to northwest alignment. This topography has been extensively modified by glacial activity, resulting in complex terraced floodplains, steeply-sloping features and alluvial fans. Throughout the parks, series of river valleys create pathways for fire spread. For example, in Banff the Bow River valley facilitates north-south fire spread in western Banff and east-west spread in eastern Banff. Other river valleys in Banff such as the Clearwater, Red Deer, North Saskatchewan and Panther create pathways for fire spread in an east-west direction. While in Yoho, the Kicking Horse valley facilitates fire spread from east-west and in Kootenay, the Vermillion and Kootenay rivers facilitate spread north-south.

South facing slopes in these valleys tend to have the most pronounced influence on fire behaviour due to insolation effects on forest fuels and the angle of incident sunlight. This factor, compounded by an alignment with regional wind directions create the potential for large, high intensity wildfires.

Banff National Park occupies 6,641 km2 within the front ranges of the Rocky Mountains and is located 134 km west of the City of Calgary. The Banff field unit is a 3,741 km2 administrative subset of Banff National Park. The Banff Field Unit also includes management of the Ya Ha Tinda Ranch (39.45 km2), the Cave and Basin National Historic Site and the Rocky Mountain House National Historic Site (Figure 1). The remaining 2,900 km2 of Banff National Park forms part of the Lake-Louise, Yoho, Kootenay (LLYK) Field Unit and includes Kootenay National Park (1,406 km2) and Yoho National Park (1,313 km2). The LLYK Field Unit also includes management of the Kootenae House National Historic Site.

Figure 1: regional Context of the Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks

Services and Infrastructure

Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks have three embedded communities that are key components in park operations. Within the eastern portion of Banff National Park is the town of Banff in the Bow Valley. Banff is a tourism-based town with approximately 9,500 residents (Town of Banff, 2014), 1,300 businesses and 3,800 hotel rooms providing essential tourism services. Also within Banff National Park is the hamlet of Lake Louise. Located in Improvement District 9, which includes all Banff National Park outside of the town of Banff, Lake Louise has a population of 1,175 (2011 census). The town of Field is located in British Columbia within Yoho National Park, and has a population of 169 (2011 census).

Transportation infrastructure is a key component of BKY. The TransCanada Highway 1 runs through the middle of both Yoho and Banff national parks, along with the Canadian Pacific Railway. In addition, Banff also contains two secondary highways (Bow Valley Parkway 1A and Highway 93 North). Kootenay National Park is bisected by a secondary highway (Highway 93 South) that is busy during the summer months.

Additional infrastructure outside the Banff townsite boundary includes:

- Visitor Experience: 5 front country campgrounds with a total of 2,500 campsites that are accessible by vehicle. Tunnel Mountain Campground hosts more than 4,000 visitors per night during peak visitation periods.

- Outlying Accommodations and Visitor Services: 3 additional hotels, 3 front country commercial cabin operations, 1 marina, 2 hostels, 3 commercial backcountry lodges, 1 backcountry commercial horse outfitter operation, 2 backcountry public shelters, 2 ski areas and a gondola sightseeing operation.

- Utilities: major power line (Altalink) and additional smaller distribution lines (Fortis), the Minnewanka Dam and associated structures (TransAlta). Buried natural gas pipelines and interprovincial critical communications lines

Additional infrastructure outside of the communities of Lake Louise and Field include:

- Visitor Experience: 14 front country campgrounds, 58 day use areas and 3 visitor reception centres.

- Outlying Accommodations: 8 additional hotels, 4 hostels, 3 commercial backcountry lodges, 10 Alpine Club of Canada huts, 1 backcountry horse outfitters, 1 ski area with a gondola sightseeing operation

- Utilities: major power line (BC Hydro) and additional smaller distribution lines and interprovincial critical communications lines.

Regional Socio-economic Attributes

Banff National Park receives the highest visitation of any national park in Canada with over 4.2 million visitors entering the park in 2017/18– the highest volume of visitors since 2000. Visitors to Banff generate both regional and federal revenues. Social and economic hubs of the Bow Valley include the towns of Banff, Canmore, Lake Louise and Exshaw; the hamlets of Harvie Heights, Dead Man’s Flats, and Lac Des Arc; and the Municipal District of Bighorn and Improvement District 9.

Kootenay and Yoho national parks receive fewer visitors than Banff, at 531,000 and 712,000 in 2017/18 respectively. As with Banff, both Kootenay and Yoho have strong ties to embedded and neighbouring communities including Golden, Radium Hot Springs and Field.

All of the communities that are within the national parks, or directly neighbouring them, have a well-informed and engaged constituency that embraces the concept of FireSmart or other applicable wildfire risk reductions activities for communities within healthy ecosystems. Parks Canada is committed to thorough consultation and collaboration with neighbouring jurisdictions, communities and businesses on all aspects of fire management.

Parks Canada has strong partnerships with its provincial neighbours: the Government of Alberta (Department of Agriculture and Forestry and the Department of Environment and Parks) and the Government of British Columbia (BC Wildfire Service and BC Parks). Parks Canada has completed several interagency prescribed fires and managed wildfire operations over the years with both of these provincial partners. It is a priority of this plan to strengthen interagency partnerships with all neighbouring agencies, thereby capitalizing on the substantial ecological gains and operational efficiencies inherent in co-managing fire across agency lines.

Climate and Weather

Under the Köppen climate classification, Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks have a subarctic climate (Dfc) with cold, snowy winters and mild summers. The climate is influenced by altitude with lower temperatures generally found at higher elevations. The period of highest fire danger occurs in late July and early August when average highs are above 20°C. The mountainous terrain and higher elevations, moderate summer temperatures and cold air subsidence occasionally trigger inversion conditions that can affect fire behaviour, air quality, visibility and highway safety during fire operations.

A west-to-east moisture gradient exists, as major weather systems transition inland from the Pacific Ocean. Located on the eastern side of the Continental Divide, Banff National Park receives 472 mm of precipitation annually. This is considerably less than in Yoho or Kootenay national parks which are on the western side of the Continental Divide in British Columbia, where 884 mm and 655 mm are received respectively. Being influenced by altitude, precipitation is also greater at higher elevations.

Prevailing winds are mainly westerly and southwesterly during the fire season, but interact with topography to produce surface winds that run parallel with valley orientation. Winds are generally stronger at upper elevations and in the transition from mountains to foothills. Dry chinook winds, typically occur east of the divide, where relative humidity values below 15% can occur during mid-winter, substantially reducing winter snow packs through sublimation. These chinook events can contribute to spring drought and often create ideal April prescribed burning conditions on south and west aspects where lingering snow cover persists on east and north aspects.

The pattern and density of lightning occurrence in the parks is largely influenced by the Continental Divide and orographic lifting of air masses as low pressure systems track from British Columbia into Alberta. A distinct “lightning shadow” exists where the density of lightning strikes drops east of the Continental Divide before regaining intensity in the foothills. As indicated in Figure 2, most of the lightning fires in BKY are located west of the Continental Divide, in the Kicking Horse Valley (Yoho National Park) and in the Kootenay and Vermillion valleys (Kootenay National Park). In Banff National Park, lightning was recorded as the ignition source for 31% of all wildfires (1985-2017) but accounts for only 10% of total area burned. While in Yoho National Park, lightning accounts for 58% of all fires but only 3% of area burned. Kootenay National Park typically experiences the highest number of lightning-caused wildfires of all three parks, with 71% of all fires occurring from lighting accounting for 90% of the total area burned.

Figure 2: Lightning caused fires in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national Parks (1980 – 2017) (Source: Parks Canada)

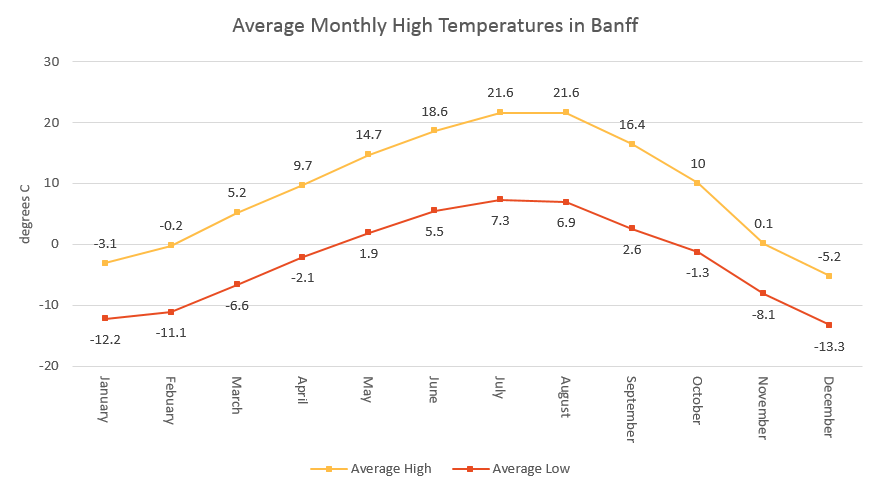

Summer in all three national parks extends from mid-June to mid-September. In the town of Banff, a centrally located Environment Canada weather station provides long-term weather data. The town of Banff has a mean temperature of 14° C, and an average high of 21.6°C (Figure 3). The maximum temperature recorded was 34°C in 1934. For all three parks, June is the wettest month on average, during which Banff receives 62mm of precipitation (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Average Monthly High Temperatures in Banff National Park. Yoho and Kootenay national parks follow a similar seasonal pattern, being a few degrees warmer or cooler depending on location.

Figure 4: Average Monthly Precipitation in Banff National Park. Yoho and Kootenay national parks follow a similar seasonal pattern, with the highest precipitation events occurring in June

Seasonal temperatures in Yoho National Park are similar to Banff (Figure 3).The mean temperature during this period is 12.5° C, with an average high temperature of 20°C. Due to the west-east moisture gradient, Yoho receives more annual precipitation on the east side of the park.

Kootenay National Park has very diverse temperature and precipitation profiles, as captured in the park's interpretive theme statement: "From cactus to glacier". Redstreak Campground near Radium Hot Springs in the south of the park will receive significantly less precipitation than the north in Vermillion Valley and is 2 to 6 °C warmer (Figure 5). This creates a longer fire season in the south of the park as snow melt occurs in this area as early as March. Temperatures and precipitation in the north of the park are similar to Banff as they near the Continental Divide. The wettest month in Kootenay National Park occurs in June, receiving 75mm of rain.

To illustrate temperature and precipitation variation between the three parks during the fire season, average daily high and low temperatures and monthly precipitation totals for the month of July are shown in Figure 5. July temperatures are typically cooler as you get closer to the Continental Divide, which forms the border between Banff National Park and Yoho and Kootenay national parks (green line in the centre of the map). Precipitation amounts are also typically higher closer to the Continental Divide, though Yoho National Park is typically the wettest of all three parks in July (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Average July Precipitation and High and Low Temperatures in Banff, Yoho national park weather stations in July. Figure illustrates the higher elevation stations recording cooler temperatures and a west – east moisture gradient

Biophysical Description

Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks all lie within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone (Figure 6). This ecozone extends from the coastal mountains in the west to the foothills of Alberta in the east. It is predominantly represented by subalpine and alpine ecosystems characterized by mixed forests of lodgepole pine, white spruce, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine fir. Stands of Douglas-fir, trembling aspen and balsam poplar occur on the warmest, driest sites in the eastern reaches of major valley systems of the lower elevation montane.

Figure 6: Canada's Terrestrial Ecozones (Source: Natural Resources Canada)

Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks are comprised primarily of three ecoregions (Figure 7): 1) the montane; 2) the subalpine and 3) the alpine (Holland and Coen, 1982). The montane ecoregion occurs at lower elevations (between 1350 and 1650 meters) and represents less than 3% of the park. However, the montane has the highest biodiversity and the highest historic fire frequency (30-50 years). Fire suppression during the 20th century has caused the most significant decline in ecosystem health and species diversity within this region, particularly impacting Douglas-fir and aspen grassland ecosites.

The subalpine ecoregion is found between the montane and treeless alpine ecoregion. It is divided into the lower (up to 2000m) and upper subalpine regions. The lower subalpine covers approximately 27% of the three parks and is dominated by dense forests of lodgepole pine, Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir. The upper subalpine makes up 24% of the three parks and is characterized by mature Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir, interspersed with dwarf-shrub meadows and avalanche path communities.

At elevations between 1800 and 2100 m, open stands of whitebark pine, limber pine and larch are found. Fire exclusion, climate change, and mortality caused by white pine blister rust have put whitebark and limber pines at risk of extirpation in the three parks. In 2012, Whitebark pine was declared Endangered and added to Schedule I of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). Limber pine has been assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) as Endangered but has yet to be added to Schedule I of SARA. However, limber pine has been designated as Endangered under Alberta’s Wildlife Act (2009).

The alpine ecoregion (between 2100 and 3400 m) covers 38% of the three parks, with 35% of it being rock, talus, moraines and glaciers. This region generally acts as a barrier to the spread of fire and presents opportunities for indirect containment of managed wildfire to optimize ecological benefits.

Figure7: Ecoregions of Banff Kootenay and Yoho national parks

Wildland Fire Regime

As seen in Figure 8, historical fire frequencies ranged between 20-50 years in the montane forests, whereas forests at slightly higher elevations (lower subalpine) had longer intervals between 50-100 years on south and west-facing slopes and 100-150 years on north and east-facing slopes. The longest fire return intervals (400 years) can be found in the old growth, upper subalpine forests where climate and snowpack likely affect fuel moisture and ignition.

In Kootenay and Yoho national parks, reference fire regime areas are defined using the climax vegetation communities (Figure 8), as determined using the Biogeocliimatic Ecosystem Classification (BEC) system (Pojar et al. 1987). Fire history research from within each of these BEC zones is used to determine the reference fire cycle.

In Banff National Park, along the east slopes of the Canadian Rockies, lightning and lightning-caused fires do not occur frequently yet evidence from studies of fire history show that fires occurred frequently in the east in many of the montane and subalpine forests prior to the 1880s and the start of the era of European settlement and the construction of the railway. Furthermore, a majority of these fires burned during periods of infrequent lightning and before the typical season for major summer thunderstorms. This incongruence between fire frequency and season of burning has been hypothesized to have been the result of anthropogenic burning by local Indigenous people to draw game species into the valley bottoms for food (Pengelly, 1993). This strong linkage between a lowered fire cycle and anthropogenic burning is also evident in the short fire cycles (25-years) observed in the southern Kootenay Valley and the Columbia Valley portions of Kootenay National Park (Gray et al., 2004).

In addition to frequency, fire size, intensity and severity also may be influenced by elevation. In the valley bottoms, fires were often smaller, as well as less intense and severe, compared to higher elevations; anthropogenic burning in the spring to create habitat for game species may have contributed to these characteristics. In the lower and upper subalpine, fires likely occurred only in those years when weather and fuel conditions would support large, stand-replacing fires.

Stand replacing fires usually consumes any evidence of previous low to moderate intensity fires in the area. Historical data beginning in 1891 can be used to identify smaller fire occurrences (Table 4). Fire suppression may have kept some fires smaller than would have naturally occurred, however this data can be used as an indication of fire starts in the park. In the Canadian Rockies, 3% of the lightning caused fires account for 95% of the area burned (Johnson and Wowchuk, 1993). Historical data from 1891 indicates 5% of the wildfires in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho in the past 120 years account for 95% of the area burned

Table 4: Fire Occurrence by Size in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho 1891-2010

| Fire Size | ≤ 1.0 ha | 1.1-10 ha | 10-100 ha | 100-1000 ha | ≥ 1000 ha |

| Total Fires | 460 | 52 | 77 | 90 | 35 |

Studies have shown that due to decades of fire suppression and climate change, the natural fire regime has been altered from a more frequent low to moderate fire regime to less frequent but high intensity fires. For example, the Verendrye Fire of 2003 in Kootenay National Park burned approximately 16,000 ha, 41% resulting in high burn severity.

Figure 8: Reference Fire Regime areas for Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national Parks.

Ecosystem Restoration and Fire Use

The negative ecological consequences of altered fire regimes and need for fire restoration in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks has been researched extensively. The reintroduction of fire into the ecosystem through managed wildfire and prescribed fire contributes to reversing these patterns, particularly in vegetation communities with shorter fire cycles such as grasslands, montane meadows, aspen and Douglas-fir forests that have suffered the greatest decline in biodiversity as a result of fire exclusion. The following sections describe how fire management activities are measured and defines ecological integrity monitoring targets over the long and medium term.

Area Burned Condition Class

The Area Burned Condition Class (ABCC) measure has been designated as a condition monitoring measure within the Ecological Integrity (EI) monitoring program for all three parks. This measure assesses the degree of departure from historic fire cycles or reference fire regime levels within a park. A full description of the development and calculation of ABCC can be found in Kafka and Perrakis (2003).

Although the Parks Canada National ABCC target is restoration of 20% of the historic fire cycle, the Management Plans for Banff, Kootenay and Yoho set a more ambitious target of achieving 50% of the long-term fire cycle.

ABCC assessments are weighted by area, which means that challenges in restoring fires in larger tracts of forest with long fire cycles differentially influence the overall park rating, obscuring the significant amount of fire restoration that has occurred in these mountain parks since the inception of the prescribed fire program in 1983 (Figure 9). The current area burned departure for Banff National Park (2017) is 82% (Table 5) with an area burned condition class of POOR. The current area burned departure for Yoho National Park (2017) is 90% (Table 6) with an area burned condition class of POOR. The current area burned departure for Kootenay National Park (2017) is 62% (Table 7) with an area burned condition class of FAIR

Table 5: Banff National Park Departure from Historic Fire Cycles by Reference Fire Regime Area in 2017

| Reference Fire Regime Area |

Reference Fire Cycle (years) |

Area Burned Departure (%) |

Area Burned Condition Class |

| Lower Subalpine | 150 | -87 | POOR |

| Montane | 50 | -66 | FAIR |

| Old Growth | 400 | -27 | GOOD |

| Subalpine (Lodgepole Pine) | 100 | -79 | POOR |

| Upper Subalpine | 200 | -85 | POOR |

| Banff Overall | 82 | POOR |

Table 6: Yoho National Park Departure from Historic Fire Cycles by Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification in 2017

|

Reference Fire Cycle (years) |

Area Burned Departure (%) |

Area Burned Condition Class | |

| Montane Spruce | 50 | -94 | POOR |

| Englemann Spruce + Subalpine Fir | 150 | -89 | POOR |

| Yoho Overall | 90 | POOR |

Table 7: Kootenay National Park Departure from Historic Fire Cycles by Fire Management Unit in 2017

|

Reference Fire Cycle (years) |

Area Burned Departure (%) |

Area Burned Condition Class | |

| Interior Douglas-fir | 20 | -58 | FAIR |

| Montane Spruce | 50 | -81 | POOR |

| Englemann Spruce + Subalpine Fir | 150 | -54 | FAIR |

| Kootenay Overall | -65 | FAIR |

Figure 9: Prescribed Fires Completed – Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks, 1983-2016

In addition to ABCC, which is the long term measure of fire restoration, Parks Canada has recently developed a medium term measure to assess the effectiveness of active management in the past two decades. This new measure assesses area burned in the past 20 years and represents the effectiveness of active management in the park. Figure 10 illustrates how the use of prescribed fire has increased the area burned in Banff National Park after four decades where fire was nearly absent. In recent years, Kootenay and Yoho have had a lower amount of prescribed fire compared to total area burned relative to Banff, due in part to the much higher amount of area burned by wildfire (Figure 11).

The 20 year percent fire restored for Banff National Park is 45%, a figure that is approaching the 50% target set by the park management plan. This 20-year management effectiveness value for Kootenay is 40% and for Yoho it is 6%.

Results from these analyses are important to determine priorities for fire restoration and management intervention as well as reporting on the overall effectiveness of fire management actions and policies to date.

Figure 10. Area burned by wildfire (WF) and prescribed (PF) fire in Banff by year 1910-2017

Figure 11. Area burned by wildland (WF) and prescribed (PF) fire in Yoho and Kootenay national parks by year 1902-2017

Work Program Scheduling

Prescribed fire and fuel management projects require advanced scheduling and planning to ensure all necessary components are addressed. The following section details the prescribed fire and fuel management plans (completed and conceptual) for the next 5 to 10 years. The number of planned prescribed fires listed in this fire management plan outnumber the prescribed fire units that can potentially be implemented during the next 5-10 years. However, by developing plans for many prescribed fire units, park managers can prioritise and implement units based on multiple objectives and take advantage of favourable fuel and weather conditions over time. Having many plans in development or completed, increases the likelihood that fire managers can implement plans and maintain operational flexibility if priorities or resources change.

Priorities for prescribed fire are based upon guidance from the national park management plans. Prescribed fires are used to achieve multiple objectives that range from ecological (e.g. habitat improvement) to operational (e.g. wildfire risk reduction). Prescribed fires are planned very carefully using established methods of fire behaviour prediction as well as experience from fire management specialists.

The planning process is generally considered to take approximately two years. Once prescribed fire has been identified as the primary tool for ecological restoration or wildfire risk reduction, fire managers develop a conceptual plan that is approved by the National Fire Management Division. If there are no major issues with the principles and objectives of the prescribed fire unit, a detailed plan that includes a site description, fire history, prescription, operations, contingency plans and communications is developed. This full plan must be presented to the national park management team, recommended by the National Fire Management Division and the Resource Conservation Manager and finally approved by the Field Unit Superintendent. Concurrent to the development of the prescribed fire plan, a basic impact assessment is also developed. This document details the environmental and socio-economic impacts and subsequent mitigations that are required during implementation of the prescribed fire. While for most prescribed fires, a basic impact assessment is adequate, due to the complex political landscape within which the three national parks exist, more detailed assessments will be developed for prescribed fires that are likely to cause significant socio-economic or ecological impacts. Throughout the planning process, the public, Indigenous nations and stakeholders will be consulted to ensure that significant concerns are addressed.

The prescription for each prescribed fire dictates the specific fire and fuel conditions under which a prescribed fire is lit. The main tool for developing the prescription is the Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System and the Fire Behaviour Prediction System. Prescriptions are developed in order to define the conditions to achieve the desired fire behaviour to meet prescribed fire objectives.

In addition to the prescription, prescribed fire plans will outline how the fire will be contained within defined boundaries. Wherever possible, natural barriers to fire spread will be used, however in certain circumstances, fuel modification using ground crews or machinery will be necessary. The plan will always include a contingency plan that dictates management actions should the fire spread beyond defined boundaries.

A full operational plan including resources requirements, costs, strategies and tactics is also included in the plan. Both ignition and holding resources should be considered in the operational plan. Lastly, each prescribed fire plan include an in-depth communications plan complete with stakeholder lists, products and desired outcomes.

Implementation of prescribed fires is carried out by specialized teams of fire management personnel who have been trained in both ignition and fire suppression. Ignition only commences after a Go-No-Go form has been completed, which includes a briefing for the Field Unit Superintendent and consultation with the National Duty Officer to ensure that all necessary steps have been taken and all resources are in place.

Prescribed Fire Implementation Priorities

Prescribed fire priority setting is based on a number of factors, including but not limited to: wildfire preparedness and values at risk protection (e.g. prescribed fire in the wildland urban interface or to serve as landscape fuel breaks); ecological objectives and priorities (e.g., wildlife habitat or grassland restoration); landscape-level fire restoration objectives (50% fire cycle restoration objectives) and management of boundary lands (e.g., capping units adjacent to provincial lands).

At present, there are several prescribed fire plans that are completed and approved or at the conceptual stage (Figures 12, 13 and 14; Tables 8, 9, 10).

Table 8: Prescribed Fire Priorities for 2019-2029 in Banff National Park

Table 9: Prescribed Fire Priorities for 2019-2029 in Yoho National Park

Table 10: Prescribed Fire Priorities for 2019-2029 in Kootenay National Park

Wildfire Preparedness and Response

Protecting the public, park infrastructure and neighbouring lands from wildfires is the first priority of the Parks Canada fire program.

Wildland Fire Preparedness

Wildland Fire Risk Analysis

A recent national assessment of fire risk and potential consequences rated Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks in the highest category (Level 1 Risk, Level 5 Consequences) based on the probability of fire occurrence and potential consequences with respect to public safety, potential infrastructure losses, and disruption of critical services. Level 5 consequence is defined as “major potential for loss of life; serious injuries with long-term effects. Widespread displacement of people for prolonged duration. Extensive damage to properties (>10 houses) in affected area. Serious damage to infrastructure causing significant disruption of key services for prolonged period. Significant long-term impact on the environment.”

This risk assessment process is used to determine the numbers and types of resources assigned to manage a park’s wildfire response, prescribed fire, and forest fuel management capabilities. For all fire management actions, Parks Canada uses the Incident Command System (ICS) to determine the organizational model and resources appropriate to the complexity of potential fire incidents. According to the risk assessment, field unit fireline preparedness resources for both Banff and LLYK must include a Type 3 ICS organization supported by a dedicated four-person Type I fire crew and minimum of 8 Type II firefighters and other ICS position resources (Figure 15).

Fig 15: ICS Configuration of a typical Type III incident response - Resources are required from both LLYK and BFU as determined by the national risk assessment exercise

As the complexity of a particular fire incident approaches field unit capacity, fireline resources can be requested through the National Duty Officer and supplied through Parks Canada resources as well as interagency resources. The Mutual Aid Resource Sharing (MARS) agreement and the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC) facilitate these reciprocal exchanges of personnel and equipment across agency lines both nationally and internationally.

Fire Management Zoning

In order to ensure socially and ecologically appropriate response to wildfires and effective use of prescribed fire for landscape level wildland fire management, the three parks are divided into three fire management zones with distinct management objectives (Figure 16). These zones are delineated based on values at risk, potential fire behaviour, and defendable landscape features such as firebreaks, rivers, lakes and rock ridges. Each zone identifies specific protocols for fire detection and control, as well as the spectrum of fireline tactics that will be considered. Zone boundaries are updated, as needed, based on recently completed management actions such as prescribed fires, fireguard construction, and wildfires that reduce overall fire risk and the need for full suppression tactics.

Figure 16: Fire Management Zone Map - Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks

To determine whether a fire will be a modified response wildfire (i.e., not a full response fire that is subject to immediate suppression) in either the extensive or intermediate zones, the following will be taken into consideration:

- Current and forecast fire weather

- Current and forecast weather

- Local, regional and national resource levels

Local, Regional and National Priorities

Intensive Fire Management Zone (Red)

Intensive zones contain communities, infrastructure, neighbouring lands, and other values that may be adversely impacted by wildfire. In the intensive fire management zone, wildfires will be managed on a priority basis to minimize fire spread using a full range of tactics. Prescribed fires that reduce wildfire risk and fuel reduction projects may be planned and conducted using intensive tactics to meet specific risk management and ecological objectives. Management actions will be focused on reducing fire risk and restricting fire growth to a very limited perimeter.

Tactics - rapid detection and initial attack. Air tankers may be used to deliver foam and long-term retardants; use of dozers, skidders, chippers and other heavy equipment are acceptable. Extensive fuel management will be carried out in this zone. Low priority sectors of larger fires may be burned out to anchor containment lines to natural barriers.

Intermediate Fire Management Zone

Intermediate zones are adjacent to intensive zones, and may contain limited facilities or infrastructure, where careful consideration is needed in determining modified suppression activities. Wildfires in the intermediate fire management zone will be managed to confine fire spread to a defined perimeter with the possibility of achieving ecological objectives. Prescribed fires will be planned and conducted using tactics that meet risk management and ecological objectives. Acceptable fire perimeters will be defined based on natural and man-made barriers and operational considerations.

Tactics - Indirect attack is the preferred response unless regional fire load, forecast weather and fuel moisture conditions indicate the need for full suppression as determined by fire analysis process. Small to medium areas of mechanical fuel reduction may be carried out around outlying facilities and park boundaries.

Extensive Fire Management Zone

In the extensive fire management zone, wildfires will be managed with minimal intervention. The extensive fire management zone is located in backcountry areas with no vehicle access. There is limited infrastructure and low visitor use.

Prescribed fires will be planned and conducted using tactics that meet ecological and risk management objectives. A prescribed fire plan using a limited range of tactics will be developed. Management actions will be focused on containing fire growth to within the fire zone.

Tactics - The extensive zone is the area wildfires will be managed for their ecological benefits. This zone has the most restrictions on fire control tactics. This includes using indirect containment and limited mop up. Limited use of helicopters for bucketing is acceptable but the use of air tankers is discouraged. Outlying infrastructure will be protected with hose lines, sprinkler systems and burning out where possible. Fuel management will be limited to small areas around backcountry lodges.

Fire Behaviour Prediction and Forecasting

For the purposes of fire behaviour prediction, vegetation cover within Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks is classified according to a national system of forest fuel types specifically intended for the prediction of fire behaviour (Taylor et al., 1997).

Throughout the fire season, fire management staff calculate fire weather indices based on the Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating system (Taylor et al., 1997). These indices are an indication of the fuel moisture based on weather (e.g., relative humidity, temperature, wind, and precipitation). Once calculated, a field unit fire danger rating can be determined.

Predictions are derived for each fuel type using computer simulation models that calculate head fire spread rate, fuel consumption, fire intensity, crown fraction burned and potential fire growth. This information is used to determine fire danger and wildfire risk levels, formulate wildfire response tactics, develop burning prescriptions for prescribed burns and plan landscape-level fire management strategies. The key fuel types found in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks are (Figure 17):

- C2 – Boreal Spruce

- C3 – Mature lodgepole pine

- C7 – Douglas-fir

- D – Aspen

- O1 – Grass

However, other fuel complexes including C4 (immature pine) and slash type fuels are also present.

Figure 17: FBP Fuel Type Map - Banff, Kootenay and Yoho National Parks

Field Unit Daily Fire Danger Rating

Fire danger is determined through a matrix that takes into consideration the following:

- Season (Spring/Fall – cured grass vs. Summer)

- Fine fuel moisture (using Fine Fuel Moisture Code – FFMC)

- Amount of fuel available to burn (using the Build Up Code – BUI)

- Wind speed

Tables 11-14 indicate the matrices for determining fire danger in the Banff Field Unit

Table 11. Spring/Fall fire danger rating matrices (prior to green up, using C7 – Douglas-fir fuel type to account for cured grass). Winds <15 km/h.

C-7 Wind 0-15 km/h - SPRING and FALL

Table 12. Spring/Fall fire danger rating matrices (prior to green up, using C7 – Douglas-fir fuel type to account for cured grass). Winds 16-30 km/h.

C-7 Wind 16-30 km/h - SPRING and FALL

Table 13. Summer fire danger rating matrices (using C3 – Mature Lodgepole Pine fuel type). Winds <15 km/h.

C-3 Wind 0-15 km/h - SUMMER

Table 14. Summer fire danger rating matrices (using C3 – Mature Lodgepole Pine fuel type). Winds 16-30 km/h.

C-3 Wind 16-30 km/h - SUMMER

Preparedness Guidelines

The Banff and LLYK field units have established guidelines that dictate the level of resourcing and service as it relates to daily wildfire danger throughout the field unit. Preparedness guidelines indicate the following (Table 15):

- Hours of duty and standby for fire personnel (fire duty officer, fire crews and additional support resources)

- Minimum response times

- Minimum resourcing levels

- Aircraft and other resource considerations

- Reporting responsibilities

| Preparedness Danger Level | Preparedness Guidelines |

|

I LOW |

|

|

II MODERATE |

|

|

III HIGH |

|

|

IV VERY HIGH |

|

|

V EXTREME |

|

|

V FIRE ONGOING |

Required Resources to be determined for the fire (if it extends beyond 1 operational period) via Parks Canada’s Fire Analysis.

|

Prevention and Detection

Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks focus on public education and awareness, risk reduction and reporting/enforcement to reduce the risk of negative wildland fire impacts. Public awareness and education will be discussed in the Communications, Public Engagement and Visitor Experience Opportunities section of this plan. This section will address wildland fire risk reduction, reporting, and enforcement issues. Table 16 indicates the fire weather thresholds under which a fire ban may be instituted through a Field Unit Superintendent’s Order as per the Canada National Parks Act. In certain other circumstances, depending on fire danger, regional fire load and resourcing considerations, a fire ban may also be considered. Appendix I includes a list of acceptable devices for use during a fire ban.

Table 16. Types of fire bans and criteria for implementation in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks

Detection

Throughout the fire season, fire management personnel use lightning detection infrastructure and software to monitor potential for fires following lightning producing events. If fire danger conditions are conducive to new fire starts, aerial detection flights using fire crews and rotary or fixed wing aircraft will be deployed. To increase likelihood of detecting human caused ignition, smoke patrol flights will also occur during periods of high and extreme fire danger.

Wildfire Risk Reduction

Since 1983, Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks have worked closely with the towns of Banff and Canmore, hamlets of Lake Louise and Harvie Heights, MD of Bighorn, villages of Field and Radium Hot Springs, local businesses, and the governments of Alberta and BC to advance all aspects of Community FireSmart Protection (Partners in Protection 2003) to mitigate wildfire risk to communities and facilities within and adjacent to the three national parks. These efforts have included forest fuel management (fuel reduction), tactical response plans, fire-resistant architectural guidelines and landscaping standards, interagency training and equipment compatibility testing, mutual aid fire response, public education and communication.

As of 2018, a total of 1500 hectares of forest fuels have been mechanically reduced in the Banff Field Unit (Parks Canada 2017). This includes 545 ha in the wildland-urban interface (WUI) and 955 ha in strategically placed landscape-scale firebreaks (Parks Canada 2017). At the two national historic sites within Banff Field Unit (Cave and Basin and Rocky Mountain), both fuel management and prescribed fire are used to contribute to wildfire risk reduction. Fuel reduction activities have been implemented in the vicinity of the Cave and Basin National Historic Site, and prescribed fire has been planned and implemented at the Rocky Mountain House NHS (2016 and 2017).

In Yoho national park, a total of 241ha of forest fuels have been mechanically reduced (Parks Canada 2017). Of this, 44 ha are in the WUI and 198 ha are strategically placed landscape-scale firebreaks. In Kootenay national park, 15 ha in the WUI and 273 ha of fuel breaks have been completed. A summary of Firesmart fuel reduction projects completed and proposed around townsites in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho date is presented in Figures 18, 19 and 20. FireSmart work is planned to expand around the communities of Lake Louise and Field starting in 2017-2018 however these units have not yet been planned in detail.

Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks will continue to develop important proactive wildfire risk mitigations including tactical response plans, fire-resistant architectural guidelines and landscaping standards, interagency training and equipment compatibility testing, mutual aid fire response, public education and communication, and fuel reduction treatments.

The safe use of prescribed fire and indirect containment of managed wildfire using fire breaks are central to reducing fuels and mitigating wildfire risk, and will be used in some areas. Where the use of prescribed fire results in unacceptable risk or impacts to the public or values at risk, fuel management projects will be the primary tool to manage wildfire risk.

To ensure the effectiveness of fuel management units, regular monitoring and maintenance activities will be required. Monitoring of units that have been implemented should include assessment of coarse and fine woody debris loads, windthrow, and regenerating vegetation. If fuel accumulation is such that the effectiveness of the unit is affected, maintenance activities should be implemented. Without proper fuel maintenance (brushing, debris piling/burning, broadcast burning), fuel abatement areas may in fact become areas that increase the wildland fire risk to a community.

Given the vast amount of fuel management activities that have been implemented in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks, the priority will be inventory, assessment and monitoring of existing fuel management areas and the identification and prioritization of any new areas that require wildfire risk reduction work. Priorities for implementation within the three parks as it relates to this fire management plan are listed in Appendix II.

Figure 18 Completed and Proposed Fuel Management Units around the Banff town site.

Figure 19 Completed and Proposed Fuel Management Units around the community of Lake Louise.

Figure 20: Completed and Planned Fuel Management Units around the community of Field, BC.

In addition to activities outlined in this fire management plan, additional vegetation management that includes fuel management and potentially prescribed fire will be described in the Developed Areas Vegetation Management Plan (DAVMP). The DAVMP documents for the parks are currently in development and will apply specifically to vegetation management in the vicinity of developed areas such as campgrounds, day use areas and other facilities.

Reporting and Compliance (Enforcement)

An efficient system for reporting wildfires as they start is critical to preventing wildfires. The three parks have a reliable system in place for routing wildfire reports to the on-call Fire Duty Officer, involving close cooperation between the Parks Canada and provincial emergency and wildfire reporting dispatch systems.

Wildfire Tactical Response

Tactical response for wildland fire in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks will be determined in context to fire management objectives such as human safety, ecological integrity, economic costs, facility protection, and predicted fire behaviour (determined through analysis of weather forecasts, fuel types, topography, etc.). Consultation between the park’s Fire Duty Officer and the National Duty Officer will determine whether or not a formal fire analysis is required. A fire analysis defines the area within which the fire will be contained, strategies and tactics to monitor or control the fire, and trigger points that may require a change in strategy or further analysis. The fire analysis will consider the fire management zone that fire is in and in the case of LLYK Field Unit, it will consider current BUI values and the prescription. The fire analysis must be approved by the Field Unit Superintendent before any actions are taken.

The field unit Fire Duty Officer will use information obtained from up-to-date fire weather observations and fire behaviour forecasts to determine the wildfire potential and specific strategies and tactics to be employed. Fire weather observations will be obtained from multiple weather stations positioned within the field unit. At present, the Banff Field Unit has three permanent weather stations as well as a quick deploy mobile weather station (Figure 21). The LLYK Field Unit has six permanent weather stations and three quick deploy mobile weather stations (Figure 21). These weather stations provide up-to-date weather information and are used to calculate fire weather indices throughout the fire season, following the specifications of the Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System (Turner and Lawson 1978). When wildfires or prescribed fire units are not close to a fixed station or the fixed station is not representative, a quick deploy station will be positioned on site to provide accurate weather and fire weather indices for the specific location.

All weather data will be archived in a fire weather database to develop prescriptions for prescribed fires and for research and monitoring purposes.

Figure 21. Fire Weather stations in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks.

A Fire Duty Officer will be on duty for the duration of the fire season from April 1 and October 31 (or later if significant fall precipitation has not yet accumulated). The Type I fire crews will be functional from April 1 to September 30 annually. Between September 30 and October 31, Type I response will be limited. Any Type I resources required after September 30 will be filled using import resources. Figure 22 indicates the typical schedule of fire management activities and resource availability throughout the year.

Figure 22. Typical schedule of activities and resource availability in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks.

Tactical response plans for specific wildfire scenarios have been developed to protect communities, other facilities, and neighbouring lands. The Town of Banff Tactical Response Plan (Town of Banff, 2007), the Field Wildfire Operations Plan (2009), and the Lake Louise Wildfire Operations Plan (2007) each outline specific tactics for the protection of values within the town boundary as well as established staging areas, reception centres and evacuation routes.

Wildland fire evacuation plans are also in place for all major campgrounds and outlying commercial facilities within Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks will be recommended by the field unit Fire Duty Officer if there is a potential threat of wildfire impingement on a facility or location. Implementation of evacuations in remote areas (e.g., backcountry campgrounds) will be led by the Parks Canada Visitor Safety team. Evacuation within the Banff townsite will be led by the Town of Banff Fire Department, whereas evacuation of the hamlet of Lake Louise will be led by Parks Canada and the RCMP. Evacuation of outlying commercial facilities is led by the facility owner/operator (e.g., Banff Gondola) with support from Parks Canada (e.g., via ferrata, ski area leaseholds, backcountry lodges). All evacuation recommendations will be approved by the Field Unit Superintendent (or designate) and will be carried out in communication with the Fire Duty Officer and the Incident Commander for the incident.

Personnel Resources

National Incident Management Teams (NIMT) are primarily tasked with responding to wildland fires and conducting prescribed fires, but may also be deployed in response to other national scale incidents or events (e.g. flooding). In addition to field unit responsibilities, the Banff and LLYK field units are each required to supply a minimum of six individuals to the NIMT program. While the primary responsibility for fire management falls within Resource Conservation, the field unit has a responsibility to contribute to the integrated NIMT program by providing staff from various functions.

From within each of the Banff and LLYK field unit fire management programs, the following positions will contribute directly to the NIMT program.

- PC-03 Fire and Vegetation Specialist

- EG-05 Fire Management Officer

- EG-04 Vegetation Restoration Specialist

- EG-03 Fire Technician

In addition to these four dedicated fire staff, two additional personnel are needed to meet each field unit’s required support for the NIMT program. In the past, Fire Information Officers from the External Relations and/or Visitor Experience functions have participated on a NIMT. The field unit management team will ensure the minimum NIMT contributions are met on an annual basis. Individuals identified as NIMT resources shall be available for shifts throughout the fire season; during which they can be deployed for up to 14 days at a time (not including travel).

Type 1 fire crews are able to perform safely and efficiently on all types of wildland fires. The Banff Field Unit will have one Type I fire crew (4 person), and LLYK Field Unit will have two Type I fire crews (Total 8 personnel).

Type II fire crews are able to respond safely and efficiently to low vigour fires (Intensity class 1 and 2). The Banff and LLYK field units will each also ensure there are a minimum of 20 Type II fire crew members available for fire management response.

Mutual Aid Agreements

While Parks Canada maintains the responsibility and authority for wildfire management within Banff, Yoho, and Kootenay national parks, the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia share boundary zones with these parks. As such, mutual aid agreements are necessary to outline management of wildland fires in these areas.

Memoranda of understanding between Parks Canada and the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia with respect to wildland fire management within the boundary zone between national park and provincial lands are in place (PCA-AB, 2009; PCA-BC, 2005) and reviewed annually. These documents outline cooperative fire management approaches with respect to:

- Fire reporting/discovery

- Responsibility

- Single and dual jurisdictional control responsibility

- Fiscal relationships and reimbursement conditions

- Liability

- Fire and vegetation management planning

- Fire prevention planning

Current MOUs do not include Rocky Mountain House National Historic Site, but Parks Canada is working with the Government of Alberta to ensure that timely wildfire response occurs on the site through regional and provincial wildfire services.

Training

Parks Canada is a member of the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC), which sets national standards for forest fire certification and training. Parks Canada subscribes to the national certification, standards and education efforts as directed by CIFFC and follows CIFFC training standards when providing or seeking assistance for wildfires requiring major management efforts. A qualification manual (Standard Operating Procedure 2006) has been established by the Parks Canada National Fire Management Division, and the minimum training and experience requirements in this manual will be applied for all fireline personnel including Incident Management Team Member positions.

Type I fire crew personnel will receive the following training and certifications:

- CIFFC Crew Member Course or (S-130 if PC trained)

- ICS 100

- Hover-exit certification

- Parks Canada Arduous Fitness Training (WFX-Fit)

- Workplace Category II Medical

- Transportation of Dangerous Goods and Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System

- Wilderness first aid (40-hour minimum)

Type I fire crew leaders will also receive ICS 200 and CIFFC Crew Leader Course (Intermediate Wildland Fire Management).

In order for both field units to meet nationally established requirements for NIMT and Type II fire management personnel (to manage a Type III response), training opportunities and certifications will be offered to a range of staff from various functions on a regular basis. The fire and vegetation management section maintains a database of all fireline ready, Type II personnel and potential NIMT members in the field unit and updates this annually. Type II fire crew and NIMT personnel will receive the following training and certifications:

- Workplace Category III Medicals

- Parks Canada Moderate Fitness Test

- CIFFC Crew Member Course (Basic Wildland Fire Management)

- ICS 100

Whenever possible, the fire management program will pay for NIMT and Type II crew member training to increase the number of available resources. In addition to these minimum requirements, the field units will support professional development opportunities (non-mandatory) to individuals whose managers approve additional National Incident Management Team participation or other specialised roles to assist the fire management program. These additional training opportunities may include, but are not limited to:

- ICS 200, 300 and 400

- Intermediate Wildland Fire Management

- Advanced Wildland Fire Behaviour

- Wildland Fire Behaviour Specialist

- Fire Information Officer training

- Position-specific ICS training

- Ignition specialist training

Ecological Research and Fire Effects Monitoring

Parks Canada operates a multi-faceted, science-based fire management program. The research and monitoring program helps fire managers assess ecosystem health as well as the effects of management actions on ecosystem components. While some program elements are based on broadly applied national reporting requirements for the Information Centre on Ecosystems database (ICE), others are designed to answer specific questions relating to environmental challenges or knowledge gaps in fire science. Examples of these more specific research projects in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks have included topics such as:

- Effect of fire on grizzly bear habitat quality;

- Effects of prescribed fire, wildfire and bison grazing on aquatic invertebrates, water quality and fish habitat;

- Effects of fire and various control methods on the spread of orange hawkweed;

- Effects of fire on mountain pine beetle population dynamics;

- Effects of two methods of logging and prescribed fire on fire behaviour and the restoration of native vegetation; and

- Effects of fire and grazing on elk foraging habitat.

Collaboration with universities, other governmental agencies, environmental groups and volunteer Citizen Science programs play a central role in this research program. The information derived from these programs are integral to informed decision making, adaptive management and timely reporting to the Canadian public on the ecological status of their national parks.

External Relations and Visitor Experience (EVRE) Plan

Overview

As world leaders in conservation, Parks Canada sustains a dialogue with Canadians, residents, visitors and stakeholders in the development and implementation of fire and ecosystem management plans. The Banff, Kootenay and Yoho National Parks Fire Management Plan prioritises actions to engage key audiences in opportunities that help inform, involve and influence their understanding and support of wildfire prevention, wildfire risk reduction, wildfire preparedness, wildfire management and response and prescribed fire implementation. The success of fire management actions in these parks is dependent upon well informed public, partners and stakeholders.

The following provides an outline of the ERVE actions within the three parks to support the Fire Management Plan and the National Fire Management Program Communication Strategy. Tactical plans will be developed through multi-functional teams to outline key activities that support project objectives, responsibilities, timelines and desired outcomes.

Purpose

- To ensure strategic, coordinated communications that develop awareness, improve understanding and encourage support for the Banff, Kootenay and Yoho National Parks Fire Management Plan.

- To provide an overview of the approach Parks Canada will take to inform, involve and influence priority audiences in fire management actions.

Public Environment

- Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks receive significant interest and coverage on fire related activities from local, regional, national and international media.

- Stakeholders have been engaged in formal consultation and planning processes with Parks Canada in the development of fire management plans including the development of fire management zoning, prescribed fire priorities, resource sharing and operational cooperation.

- Parks Canada has run engagement programs with Indigenous nations on the development of prescribed fire and/or fuel management plans, to determine what their interests may be as they relate to the specific area and plan.

- Partners and stakeholders are very interested in sharing Parks Canada stories and information on fire management with the public.

- Parks Canada has strong partnerships with its provincial neighbours: the Government of Alberta (Department of Agriculture and Forestry and the Department of Environment and Parks) and the Government of British Columbia (BC Wildfire and BC Parks) to support communication efforts.

- For several decades, Parks Canada, communities and leaseholders have joined forces in fire management initiatives including forest thinning at the interface, tactical response planning, interagency training, mutual aid response, public education and awareness, and risk mitigation measures with significant success. These efforts have resulted in local communities that are well informed, supportive of fire as an ecosystem process, and well protected from the adverse impacts of wildfire.

- This fire management plan integrates and supports the strategic goals of community plans, such as those in Canmore, Banff and Radium Hot Springs, and the interests of commercial tourism operators within and adjacent to the parks. Parks Canada benefits greatly from a mutually supportive relationship with local and regional stakeholders.

Indigenous Engagement

As stated by the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change in 2017, “Indigenous peoples are the first stewards of our water, air and land, and we must work in partnership to protect our environment.” Following this statement and the government’s commitment to reconciliation, Parks Canada will continue to seek out opportunities to actively engage and involve interested Indigenous nations in fire management programming for the three national parks. From historical records, it is well known that Indigenous peoples in many areas of North America routinely used fire as a tool to draw wildlife into the valleys to ease hunting and maintain open grasslands. Providing opportunities for Indigenous involvement in the fire management program is essential to ensuring a successful program that not only respects this historical, cultural and ecological connection to fire management but also their broader connections to the landscape on a whole.

Engagement and involvement in the fire management program will be based on the interests of the individual Indigenous nations. Identifying these interests and how they would integrate into the planning and implementation of the fire management program will be a key element to the Indigenous engagement program.

Audiences

| Audience | Interests |

|

Canadians in target markets (Bow Valley, Columbia Valley, Calgary, Toronto, Vancouver)

|

|

|

Visitors to Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national parks

|

|

| Residents, Communities, local businesses The Town of Banff, Hamlet of Harvie Heights, Town of Canmore, MD of Bighorn, Hamlet of Lake Louise, Improvement District 9, community of Field, Village of Radium Hot Springs, Town of Golden, Columbia Valley businesses and outlying commercial tourism operators |

|

|

Stakeholders and Partners

|

|

|

Youth and educational institutions

|

|

|

Parks Canada staff

|

|

|

Indigenous

|

|

ERVE Goals, Objective, Strategies

|

Goal: Inform

|

||

| Objectives |

|

|

| Audience | Canadians, park visitors, stakeholders | |

| Strategies | External Relations |

|

| Visitor Experience |

|

|

|

Goal:Engage

|

||

| Objectives |

|

|

| Audience | Stakeholders/partners, Indigenous nations, residents/communities and local businesses, youth and educational Institutions |

|

| Strategies | External Relations |

|

| Visitor Experience |

|

|

|

Goal: Improve Internal Communications and Processes |

||

| Objectives |

|

|

| Audience | Parks Canada staff in Yoho, Kootenay and Banff national parks |

|

| Strategies | External Relations |

|

During a wildfire or prescribed fire, a Fire Information Officer (FIO) is part of the Incident Command structure, reporting to the Incident Commander, and responsible for coordinating communication products pre-, post- and during incidents.

Key Messages

- Through its fire management program, Parks Canada is committed to ensuring public safety and reducing the risks of wildfires. The safety of people and structures is a top priority, and we focus our suppression efforts on fires where there are values at risk.

- Parks Canada is a leader in fire management: our management, facility protection and ecosystem restoration work is based on decades of experience and research.

- The Fire Management Program reduces wildfire risks to people and infrastructure through the careful planning and implementation of fuel reduction and prescribed fire projects.