Six champion travellers: Parks Canada's longest-migrating species

Some of the best-known species found in Canada’s national parks are citizens of the world. They migrate across oceans and continents to escape bad weather, find food and breed.

To protect these long-distance travellers, we have to range as far as they do. They need networks of protected areas to keep them safe throughout their migration and at all stages of their lives.

Here’s a selection of our champion travellers—insects, mammals, reptiles and birds. Parks Canada is going the distance to make sure they keep going the distance.

1. Arctic tern – 71,000 kilometres round trip

If the Arctic tern had a family motto, it might be “To the ends of the Earth!”

This modest-sized bird with its black cap and forked tail is the longest-migrating animal in the world. Breeding in the Arctic, sub-Arctic and Atlantic regions in the summer, it makes a long zigzagging trip down to Antarctica for the winter… and then retraces its route in the spring.

Over its lifetime, this champion traveller might migrate over 2 million kilometres—equivalent to flying to the moon and back two and a half times

Where you might see Arctic terns:

Terra Nova and Gros Morne National Parks (Newfoundland); Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve (Quebec), Prince Edward Island National Park, and of course northern National Parks such as Quttinirpaaq (Nunavut) and Wapusk (Manitoba).

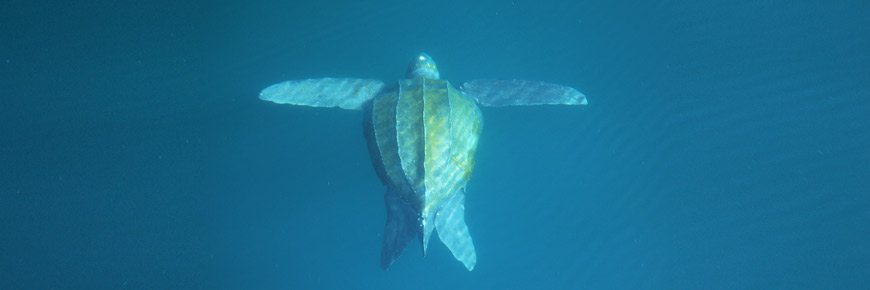

2. Leatherback sea turtle – 18,000 kilometres round trip

Seeing this endangered giant drifting in sunlit seas, its long fore-flippers spread like wings, is a sight to remember.

One of the world’s largest reptiles, the leatherback can weigh as much as a small car. Leatherbacks are true world travellers, laying their eggs on the southern shores of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans and migrating north to feed (they love jellyfish). In the summer, Canada’s East Coast is home to one of the largest densities of leatherbacks in the North Atlantic.

Leatherbacks are at risk of entanglement in fishing gear and from ocean pollution, particularly plastic. One way to help sea turtles is to use as little plastic as you can—and to refuse single-use plastics like straws and bags.

Where you might see leatherback sea turtles:

Leatherbacks are hard to spot and, as an endangered species, are best given lots of space.

Atlantic population: Cape Breton Highlands National Park (Nova Scotia), Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve (Quebec) and Terra Nova National Park (Newfoundland).

Pacific population: Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site (in British Columbia).

3. Humpback whale – 10,000 kilometres round trip

Humpback whales excel in two skills that most of us grow out of—jumping and singing.

Their eerie, complex songs can be heard at a distance of thirty kilometres underwater. As acrobats they are equally impressive, sometimes leaping clear of the waves or slapping the surface with their fins or tail flukes.

The North Pacific population of humpbacks passes through Canadian waters twice a year, calving in the warm waters of Hawaii and then heading north to Alaska to feed. Atlantic humpbacks migrate between the Caribbean and the Arctic.

While North Atlantic humpbacks are not considered at risk, the North Pacific population is classified as a species “of special concern” under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. In addition to such threats as vessel strikes and sound pollution, humpbacks must also cope with climate change, which could alter ocean circulation patterns and affect the distribution of their prey.

Where you might see humpback whales :

North Pacific population: Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site, Pacific Rim National Park Reserve and Gulf Islands National Park Reserve.

North Atlantic population: Various protected areas such as Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park and Forillon National Park (both in Quebec) and Cape Spear Lighthouse National Historic Site and Terra Nova National Park (Newfoundland).

4. Whooping crane – 7000 kilometres round trip

North America’s tallest bird, the whooping crane nests in a single remote corner of Canada—the boggy reaches of Wood Buffalo National Park. In autumn, the population migrates 3500 kilometres south to the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas.

The story of the whooping crane is one of the great species-recovery sagas in the world. In 1941, the population was at an all-time low of 21 birds. Through joint American–Canadian efforts, that number has risen to roughly 800 worldwide (including captive birds).

Parks Canada continues to work with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to monitor crane habitat and identify important stopover points for migrating whoopers.

Where you might see whooping cranes:

Wood Buffalo National Park (Alberta/Northwest Territories), Grasslands National Park (Saskatchewan).

5. Monarch butterfly – 6000 kilometres round trip

If you weigh just half a gram, flying all the way to Mexico takes everything you’ve got.

This trip is reserved for a special generation of monarchs in Canada—those that emerge in late August and September every year. This generation lives six times longer than other monarchs (whose lifespans average around a month). The long-lived monarchs don’t have the urge to reproduce; all their energy is put into creating fat stores. This allows them to make the incredible journey south to a mountainous forest in central Mexico.

Monarchs are listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. You can help them by planting milkweed, the only plant that monarch caterpillars can eat.

Where you might see monarch butterflies:

An excellent place to see migrating flocks is Point Pelee National Park (Ontario), which marks one of shortest traverses of the Great Lakes. Point Pelee is working hard to preserve the monarch’s home—the park’s savannah habitat.

6. Barren-ground caribou (Porcupine herd) – 4,800 kilometres round trip

The Porcupine herd is one of eight major populations of barren-ground caribou that inhabit Canada’s North. This herd ranges across northern Yukon, northeastern Alaska and part of the Northwest Territories, traversing Yukon’s Vuntut and Ivvavik national parks. The traditional calving grounds for the Porcupine herd are the coastal ranges of Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Caribou are not only an important prey species for wolves and bears but are vital to the cultures of Indigenous people. For thousands of years, Yukon’s Gwitchin and Inuvialuit peoples have depended on the Porcupine herd for food, clothing and tools.

Where you might see the Porcupine Caribou Herd:

Vuntut and Ivvavik national parks, Yukon.

- Date modified :