Visitor Guide

Fort Anne National Historic Site

Welcome to Fort Anne National Historic Site.

Fort Anne National Historic Site Visitor Guide

On this page

- Pjila’si – Welcome – Bienvenue

- Make the most of your visit

- Map

- For your safety

- History

- The Mi’kmaq in Nme’juaqnek

- The French arrive: the first Port-Royal

- The Scots and Charles Fort

- The French and the fort at Port-Royal

- The British and the fort at Annapolis Royal

- Treaties

- The Black Loyalists

- Commemorations and celebrations

- The Officers’ Quarters

- The Garrison Graveyard

- How to reach us

- More to discover

Pjila’si – Welcome – Bienvenue

Come walk in the footsteps of those who came before.

This is Nme’juaqnek—place of bountiful fish. For the Mi’kmaq, this place where two rivers meet has traditionally been an important fishing area and a central gathering place.

In the 1600s and 1700s, this was the centre of early European colonization and settlement in an area called Mi’kma’ki by the Mi’kmaq, Acadie by the French, and Nova Scotia by the British.

One of the most contested places in North America; this has always been Mi’kmaw territory. Both the French and the British held military control here at times and fought for it at others.

Guarding this rich history as well as the remains of both French and British fortifications, Fort Anne is the first operated national historic site in Canada, designated in 1917.

Make the most of your visit

1. Plan to spend between one and two hours discovering the site.

2. Start your visit at the Officers’ Quarters Museum. New interactive exhibits highlight the site’s dramatic history.

3. Youth can have fun with the Xplorer booklet available at the Orientation Room of the Officers’ Quarters Museum.

4. View the 1621 Royal Charter that gave Nova Scotia its name. Learn more about the Scots’ short stay and legacy.

5. Try on some reproduction period clothing.

6. Enjoy a bird’s eye view of the French fortifications, and explore the model’s details of a moment in time – 2:15 pm on a summer afternoon in 1710.

7. The site was attacked at least 13 times and the area changed hands seven times between the French and the British. Explore the Timeline Wall to learn more.

8. View Our People and the Fort Anne Heritage Tapestry. The paintings and panels are a visual telling of stories and events that have shaped the history of Fort Anne and its surrounding area.

9. Explore the earthwork fortifications and learn about a “Vauban” fort.

10. Feel the cool air in the 1708 Powder Magazine and the “Black Hole”.

11. Make the most of your visit. Take the walking path (750m) with interpretative panels and majestic views of the basin. Take selfies from the Red Chairs and share your images at #sharethechair.

12. Postcards, booklets, posters and other products are available for sale at the Orientation Room of the Officers’ Quarters Museum.

Map

This map shows the features of interest and facilities and services at Fort Anne National Historic Site.

Legend

Walking path (accessible)

Walking path (accessible)

Footpath

Footpath

![]() Parking

Parking

![]() Washrooms

Washrooms

![]() Picnic area

Picnic area

Features of interest

1. Officers’ Quarters Museum

2. Parade square

3. Powder magazine

4. Sally port

5. Black hole

6. Earthworks

7. Jean Paul Mascarene monument

8. Charles Fort and d’Aulnay monument

9. Samuel Vetch monument

10. Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons monument

11. Queen’s Wharf

12. Perimeter Trail

13. Fort Anne cemeteries

14. Cold case burial site

For your safety

The Officers’ Quarters Museum, the public washrooms and pathways are wheelchair-accessible.

Use caution on the steep, grassed hills (earth walls).

Watch for low doorways and uneven steps.

Smoking is not permitted in the buildings.

Please carefully supervise young children.

Pets on a leash are permitted on the grounds.

Only service animals are allowed in the museum.

History

The Mi’kmaq in Nme’juaqnek

As the first inhabitants of this region, the Mi’kmaq draw their identity, their beliefs, and their way of life from this place. The rivers that end here provided routes through Mi’kma’ki and to traditional meeting places. The Mi’kmaq moved through land according to the seasons, drawing from it as they needed, sharing its bounty, and caring for it so that it would remain in balance.

The French arrive: the first Port-Royal

In 1604, an expedition led by Pierre Dugua Sieur de Mons sailed into the basin which his cartographer, Samuel de Champlain named Port-Royal. In the summer of 1605, they established their fur-trading post near today’s Port-Royal National Historic Site, and planted wheat in the present location of Fort Anne. In 1613, an expedition from Jamestown, Virginia burned the Port-Royal settlement, an attack that marked the beginning of conflict between Britain and France for control of the region.

The Scots and Charles Fort

In 1621, Sir William Alexander received a royal charter to establish a Scottish colony in North America: Nova Scotia (Latin for New Scotland). In 1629, seventy settlers sailed with Sir William the Younger to start new lives here. Only half survived the first winter, but they stayed and more colonists arrived. They built Charles Fort, but after three years they were evicted by treaty when England ceded the territory to France in 1632. The remains of Charles Fort lie beneath the soil of Fort Anne’s outer works. Their legacy is the name of our province, Nova Scotia, its flag and coat of arms.

The French and the fort at Port-Royal

In 1636, Charles de Menou d’Aulnay brought a group of French colonists from La Have, on the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, and built a fort on this site. Soon after, more came from France to the new community of Port-Royal. With hard work, and good relations with the Mi’kmaq, the population grew. As the Acadian settlements grew in the area and spread further up the Bay of Fundy, Port-Royal became the cradle of Acadia and its capital.

Port Royal was often a target in French and British imperial conflict. When it was under French control, it was the closest French centre to British forces in New England, and under British control it was surrounded by Acadian colonists and Mi’kmaq who often allied with the French. The French increased their military presence in the early 18th century. Despite the turmoil, Acadian families carried on, even when British forces took Port-Royal.

A succession of five forts were built and remodelled over a 170 year period. In 1702, Pierre-Paul Delabat designed this simple fort inspired by designs of Louis XIV’s royal engineer Vauban. In the 1740s and 1790s the British made additions completing the design we see today.

The British and the fort at Annapolis Royal

In 1710 Port Royal fell to the British for the last time and Port-Royal was renamed Annapolis Royal in honour of Queen Anne. Acadians were given 2 years to move to French territory, however most chose to remain here. From 1713 to 1749, the British governed Nova Scotia from Annapolis Royal.

During the War of the Austrian Succession (1744- 1748), Quebec, Louisburg, and France sent expeditions to retake the fort and to re-establish French Acadie, but were unsuccessful.

In 1749, Halifax became the new capital. Annapolis Royal, however, had one more role to play. In December 1755, 1,664 Acadians were deported from the Annapolis Royal area.

Britain renewed attention on the fort at Annapolis Royal during the American Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the War of 1812. They began to call it Fort Anne during the nineteenth century, but its military importance declined, and the last garrison withdrew in 1854.

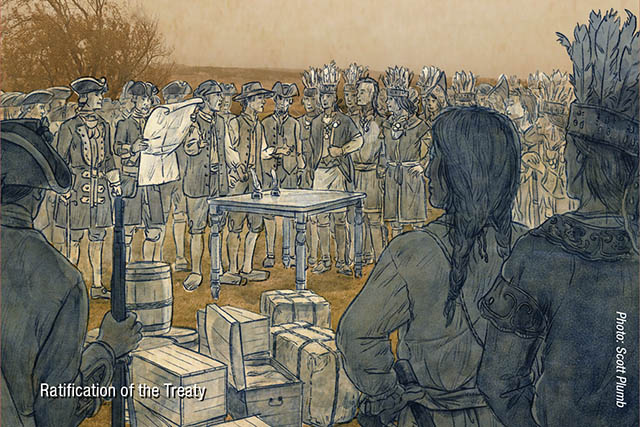

Treaties

The Mi’kmaq developed relationships of trade, religion, and family with the French, and often supported their wars against the British. After the British took control in 1713, the Mi’kmaq and other First Nations allies resisted and waged a war in the 1720s. During that time the British held 22 Mi’kmaq hostage in the fort. This conflict ended with a treaty, negotiated in Boston, and ratified here between 1726 and 1728.

The conflicts renewed after the British moved their capital to Halifax and continued during the imperial wars of the time. Open warfare between the Mi’kmaq and the British was brought to an end with the 1760-61 treaties of Peace and Friendship.

The treaties, however, have not been respected by governments since, and the Mi’kmaq have struggled to have them acknowledged. In the 20th century they were reaffirmed multiple times by the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Black Loyalists

After the American Revolutionary War, many former slaves who fought for the British in exchange for their freedom, Black Loyalists, settled in this region. A century later some of their descendants lived in these Officers’ Quarters after the British left, before this became an historic site. Fort Anne continues to interpret the story of Rose Fortune, daughter of Black Loyalists, who operated her own carting business and informal police service in Annapolis Royal in the 19th century.

Commemorations and celebrations

The last garrison left in September 1854 and the British government leased the grounds. The community used the land to graze animals, play sports and explore the ruins. In 1881, the fort’s lease holder demolished the 100 year-old blockhouse, and public outrage sparked a local preservation movement. In 1883, ownership was transferred to the Canadian government and the Garrison Commission was formed to run Fort Anne as a “park and public place of resort”.

In 1897, for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, the federal government invested in upkeep of the site, and erected the Sieur de Mons statue in 1904, for the 300th anniversary of his first effort at settlement in what would be Canada.

On January 24, 1917 Fort Anne became the first operated “Dominion Park” in what is today’s Parks Canada. In the 1920s ceremonies were held to recognize the 300th anniversary of Scottish settlement.

The Officers’ Quarters

Prince Edward, commander-in-chief of the British forces in Nova Scotia, and later Duke of Kent, constructed the Officers’ Quarters in 1797, as part of his grand plan to upgrade British defences. Initially, this building housed two field officers. Its use changed over time as other structures deteriorated or burned, and as the number of soldiers dwindled. During the first half of the 1800s various people occupied it including the hospital assistant, officers, non-commissioned officers, soldiers and their families.

After 1854, the British government leased the grounds and the Officers’ Quarters, the only surviving British barracks, served as a private residence, a private school, a multifamily dwelling, and a tenement. In the 1880s repairs were undertaken and part of the building served as the caretaker’s house until 1917. The museum and park office opened in 1918. In the 1930s, it was restored to create a “modern fireproof museum”.

The Garrison Graveyard

During the French period and much of the early English period, wooden crosses were used to mark burials. These have deteriorated over the centuries, so although over 2000 people are buried in the graveyard there are only 234 markers.

The cemetery of the Parish of Saint-Jean-Baptiste is located here; Acadian residents of the Port-Royal area, members of the French garrison, officials of the French administration at the fort, and their families were buried here.

Following the British capture of the fort in 1710, it became an Anglican cemetery. The burial ground served the needs of the garrison at the fort, as well as the needs of the civilian population of the Town of Annapolis Royal. The last burial took place in 1940.

The cast iron fence dates from the mid-1870s and was produced by Munro and O’Neill of Lower Water St. Halifax. It is a rare example of Nova Scotia cast-iron work from this time period, and was restored in 2017.

How to reach us

Fort Anne National Historic Site

P.O. Box 9,

Annapolis Royal

Nova Scotia

B0S 1A0

Civic Address

323 St. George St

Annapolis Royal

Nova Scotia

B0S 1A0

Telephone

902-532-2397

902-532-2321

(off-season)

More to discover

Fort Anne is part of the Parks Canada system of special places protecting and presenting Canada’s cultural and natural heritage for this and future generations.

While in the area, watch for the beaver symbol on highway signs. It will lead you to nearby Port-Royal and Melanson Settlement National Historic Sites and Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site.

- Date modified :