Boreal forest

Cape Breton Highlands National Park

Cape Breton Highlands National Park’s boreal forest is found at elevations above 330 metres, primarily on the south-central and western highlands and protects over 20% of the boreal forest in the northern Cape Breton ecosystem.

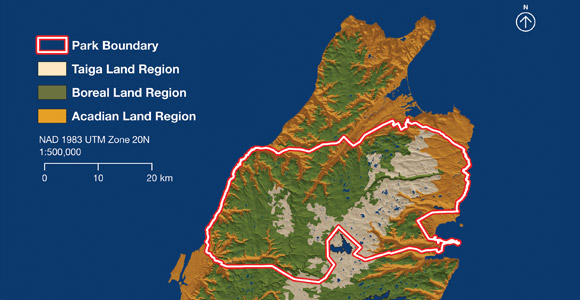

Map showing the location and extent of forest types in Cape Breton Highlands National Park

The deep, dark boreal forest

The boreal forest is made up mostly of balsam fir and white birch, with smaller amounts of white spruce and black spruce. Compared to the Acadian forest, the mature boreal forest has relatively few species. Dense shading and acidic soils prevent extensive growth of shrub and herbaceous layers. Mature trees are relatively small and short-lived, surviving for 50 to 100 years. Common plants on the forest floor include starflower, bunchberry, clintonia, wild lily-of-the-valley, twinflower and sphagnum moss.

Although the boreal forest region extends over most of northern Canada, over half of it has been disturbed by human activities such as logging or mining, making long-term studies of the boreal forest difficult. For this reason and others, protection of the boreal forest within Cape Breton Highlands National Park is important.

Characteristic boreal forest animals include the moose, lynx, snowshoe hare, red squirrel, hermit thrush, boreal chickadee and gray jay.

The spruce budworm, the moose and the boreal forest

Balsam fir is the dominant tree species in the boreal forest of northern Cape Breton. The spruce budworm, in spite of its name, loves to eat balsam fir more than anything else. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, softwood forests in northern Cape Breton were heavily damaged by the spruce budworm which is nearly always present in softwood forests to some degree but every 30 years or so has a population explosion. When the population explosion coincides with a peak in the concentration of balsam fir, it's a recipe for renewal of the forest landscape.

Normally after a major natural event like an insect infestation or forest fire, the treeless land is colonized by plants like raspberry or bracken fern. Then, slowly, new trees start growing in. The colonizing trees usually include white birch, mountain ash, pin cherry and balsam fir. About 20 years after the major natural event, the new forest is mostly composed of birch and fir. The white birch grows very quickly compared to the balsam fir and takes over. This makes perfect habitat for the shade-loving balsam fir. After a few more decades, most of the forest is balsam fir, with a few white birch trees scattered about. After another few decades, balsam fir takes over completely, choking out other species and creating monoculture stands – perfect for spruce budworm. It's a continuous cycle of destruction by budworm, opening of the land, and re-colonization by balsam fir.

However, in Cape Breton Highlands National Park there is another player in the game. In the summer there is plenty of food for moose, but in the winter they depend mainly on twigs and bark of white birch and other deciduous species, as well as balsam fir. When the spruce budworm outbreak opened up the boreal forest, the regenerating trees provided an immense food supply for the moose. With an abundance of food and no significant natural predators (as wolves were extirpated or locally extinct from this area), the moose population in the park exploded.

Now, the regeneration of the boreal forest is stalled due to overbrowsing by the large moose population in Cape Breton Highlands National Park, which often eats 50-60% of the new growth in the areas hit by budworm. Over 15 years of monitoring by park staff and other researchers has shown that the boreal forest is not recovering and is being converted to grassland.

Related Links

- Bring Back the Boreal project

- Trees of the Boreal Forest

- Boreal Forest - Hinterland Who's Who

- Date modified :