Connecting wildlife habitats for a healthy planet

Parks Canada works with diverse partners to connect wildlife habitats in many ways. We maintain ecological corridors, wildlife crossings, and remove barriers to help animals—and people—thrive.

Many animals need to reach habitat well beyond the boundaries of protected areas to survive. They travel long distances to find nourishment, shelter, mates, and to raise their young. In order for species to safely access what they need to survive, protected areas need to be connected. Watch this video to learn more:

Connecting habitats for a healthy planet

Text transcript

[Photos of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, and Rouge National Urban Park flash across the screen.]

Recognize any of these places?

[People hiking and camping together.]

We often think of them as wild spaces for people to explore and enjoy, but they're also safe spaces for nature to thrive.

[A herd of caribou graze and lounge in the sun on top of a lightly snow-covered space. A bison and prairie dog stand together in an open grassland.]

[People walk along a pathway through a forest. An Orca surfaces and blows air through its spout.]

Protecting natural lands and waters like these is a key way to slow biodiversity loss and ease the effects of climate change.

[A bird sings while perched on a cattail that is swaying in the wind. A Polar Bear and its cub stand near the water.]

[A Parks Canada employee uses a tool to collect soil samples from the ground. Another employee stands nearby and records the data.]

We know that and we're trying to do more of it.

[Aerial view of Parks Canada employees completing field work. The camera quickly ascends, revealing a large grassy landscape surrounding the employees.]

In fact, Canada has already conserved over two million square kilometres of its land and marine areas and we're trying to increase that number as quickly as we can.

[A graph appears, revealing that the total amount of protected land and marine areas has greatly increased since 1990.]

[The graph reveals the planned increases to protected land and marine areas until 2030.]

This is good news.

[People walk their dog through a park. Two kayakers paddle along a rocky coast.]

But protecting more lands and more waters is just one piece of the puzzle.

[A turtle slowly crawls across greenery toward a water source. A moose moves through a forest during the winter.]

For protected places to be fully effective at conserving nature, we need to make sure species can safely access what they need to survive.

[An illustrated landscape appears. Plants and animals appear across the landscape. Protected areas appear on the landscape. Some species are located within the protected areas and some are located outside of the protected areas.]

And sometimes those things are beyond the boundaries of a protected area.

[A young bear runs across a road. The Parks Canada logo appears in the middle of the screen and fades away.]

So what can we do?

[Parks Canada employee, Liz Nelson, speaks into the camera.]

I think when I first started working at Parks, I really imagined borders to be this very obvious thing, like a fence…but species don't see that division.

[Name Tag] Dr. Elizabeth Nelson, Ecosystem Scientist, Parks Canada

This is Dr. Liz Nelson.

She's an expert in conservation planning at Parks Canada.

[An illustrated graphic appears with plant and animal species spread across the screen. Yellow arrows appear, indicating movement. Labels appear, indicating that animals travel to “mate”, “give birth”, “find food”, “disperse seeds”.]

Species on land, in the water and in the air travel to mate, give birth, find food, and disperse their seeds.

[Liz reappears on the screen and speaks into the camera.]

And species will move in and out of the park many times through their lifetime, often many times during the day.

[An illustration of two caribou appear. A label appears, indicating the caribou are standing in Gros Morne National Park.]

Take this example.

[Two caribou walk through a grassy landscape.]

Scientists at Natural Resources Canada tracked a herd of caribou around Gros Morne National Park for more than a year.

[An illustrated map appears. A dot begins moving across the screen, navigating between Gros Morne National Park and nearby Main River Waterway Provincial Park.]

You can see that the caribou spend plenty of time moving between Gros Morne and a nearby provincial park.

Allowing this sort of free flowing movement is exactly what we're trying to do.

[Liz speaks into the camera.]

Even when we plan protected areas to provide this safe haven for species and ecosystems we care about, we have to recognize that those species and ecosystems are always moving in and out of those spaces.

[A herd of caribou walk through a snowy landscape.]

[A Grizzly Bear and its cub walk across a road. Camera moves back to reveal a snowy mountain valley. An insect crawls along a plant. A fox crosses a road and pauses, looking into the camera.]

And we want to create space across larger landscapes to really give them the best chance of survival.

[A river flows through a forested fall landscape. Sheep run along a mountainside. A river flows through a green forest. An Eriophorum plant blows in the wind.]

The idea that connectivity is important isn't new, by the way.

Movement and connection have always been an integral part of Indigenous knowledge systems.

[A sheep stands on a rocky mountainside. A river flows through a human-made drainage system. A salmon swims near a river bottom. Two goats walk along a roadside. Two caribou rest in a snow-covered landscape.]

Aside from allowing access to basic necessities, unimpeded movement, inside and outside of protected areas, is critical for genetic exchange between populations.

[A bird walks along a beach. Two wolves run in a field. A beaver swims in a river. A sheep jumps over a roadside barrier.]

It also gives species space to move and adapt to changing climate conditions, which is only going to become more necessary.

When we block connections, we create problems for species and ecosystems.

[An illustrated landscape appears. Common barriers begin appearing on the map, including boats, a road, agricultural lands, and a large fence.]

Ocean traffic, dams, roadways, agricultural lands and fence ways are all examples of barriers that inhibit species movement and the flow of natural processes.

[A herd of caribou appear to stop at a barrier. A Bobcat hides in the shadows on the edge of a forest.]

[The illustrated landscape reappears. A large majority of the landscape fades away, leaving small fragments of protected areas. Lines begin to move within the protected areas, indicating that it’s difficult for species to move between protected areas.]

When we build these things, we're left with these small fragments of natural landscapes, isolating species who rely on movement to survive.

So really, what can we do?

[Pathways appear between the protected places, representing free movement.]

Our goal is to keep ecosystems connected, both within and outside of protected areas.

[Arctic birds fly over the ocean with an iceberg in the background. Cars drive fast on a highway. A highway underpass appears, illustrating one example of ways people can restore connections. Caribou run across a snowy landscape.]

We can't turn back time, but we can restore connections between habitats that have been lost and maintain the ones that remain.

[Examples of human-made structures that enhance connectivity for species appear on screen, including a highway underpass, a pathway underpass, and a curb ramp with a salamander climbing up.]

And those connections can come in all shapes and sizes.

[A photo of a highway overpass appears on screen. A wolf uses a highway underpass. A turtle uses a highway underpass.]

At Parks Canada, we're building highway overpasses and underpasses that help species across safely.

[An owl sits on the ground amongst greenery. An aerial view of Parks Canada employees standing next to a creek channel.]

We're restoring connections between protected areas and other habitat, by supporting ecological corridors.

[A backhoe clears debris from a creekbed. A flock of Greater Sage-grouse stands in a field. A barbed wire fence appears, representing a barrier.

We're removing human infrastructure that limits movements and natural flows,

[A member of the Haida Nation speaks to visitors in Gwaii Haanas. A group of snowmobilers cross a break in the ice of the northern coast of Baffin Island.]

We're learning from Indigenous knowledge holders how cultural

and ecological connections to the landscape are weaved together.

[Parks Canada employees remove debris from a creekbed. A small fish swims along the bottom of a creek.]

We're restoring creek channels and natural water flows for species at risk.

[Parks Canada employees and partners talk amongst one another.]

We're also working with universities, conservation groups, and other

governments to track species movements so we can prioritize new areas

[A Parks Canada employee inserts a memory card into their laptop to check a wildlife camera.]

to protect and confirm if existing connections are being used.

[Cattle graze in a large agricultural field. The illustrated landscape reappears with the connected protected places. Labels indicate examples of different individuals and organizations who manage protected areas, including “Marine Refuges”, “National”, “Provincial & Terrestrial Parks”, “National Wildlife Areas”, “Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures”, “National Marine Conservation Areas”, “Marine Protected Areas”, “Indigenous Protected & Conserved Areas”.]

The land that connects natural spaces is managed by all sorts of different individuals and organizations, meaning

no one group can tackle the challenge of connectivity alone.

[The labeled groups move into a circle. A web forms between them, indicating that the groups must work together.]

We need to think beyond boundaries and beyond borders: municipal,

provincial, federal, even continental.

[An aerial view of a river. Parks Canada employees and partners work together to move an inflatable watercraft through a mountain river.]

To protect nature, it needs to be connected, and we need to work together.

[A Parks Canada employee walks across a vast grassland.]

Find out more about how Parks Canada is connecting landscapes for conservation at the link on your screen.

A challenging game of hopscotch

National parks and national marine conservation areas in Canada are home to iconic wildlife, including many species at risk. Yet protected areas, like national parks, are often not connected to other natural areas. Human activities, like urban development, roads, and logging, can all occur around national parks.

This leads to wildlife populations being isolated—cut off from the surrounding landscape.

More and more, animal and plant species are becoming stranded on “islands” of habitat. Traveling between patches of habitat—whether on the land, in water, or in the air—becomes a challenging game of hopscotch for wildlife.

Ecological connectivity

Parks Canada works with partners across North America to make it easier for wildlife to move freely between habitats. These actions support ecological connectivity. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines ecological connectivity as “the unimpeded movements of wildlife and flow of natural processes that sustain life on Earth”. Maintaining connectivity—both inside and outside of protected areas—is a global strategy for halting the loss of biodiversity.

When wildlife flourish, so do we.

Wildlife are always on the move to access what they need. Parks Canada looks at ways to connect protected areas to each other, and to other core habitats, to safeguard wildlife. We maintain and protect existing natural areas, and improve connectivity within protected areas. We are working with partners to create a network of protected and conserved areas across the country.

-

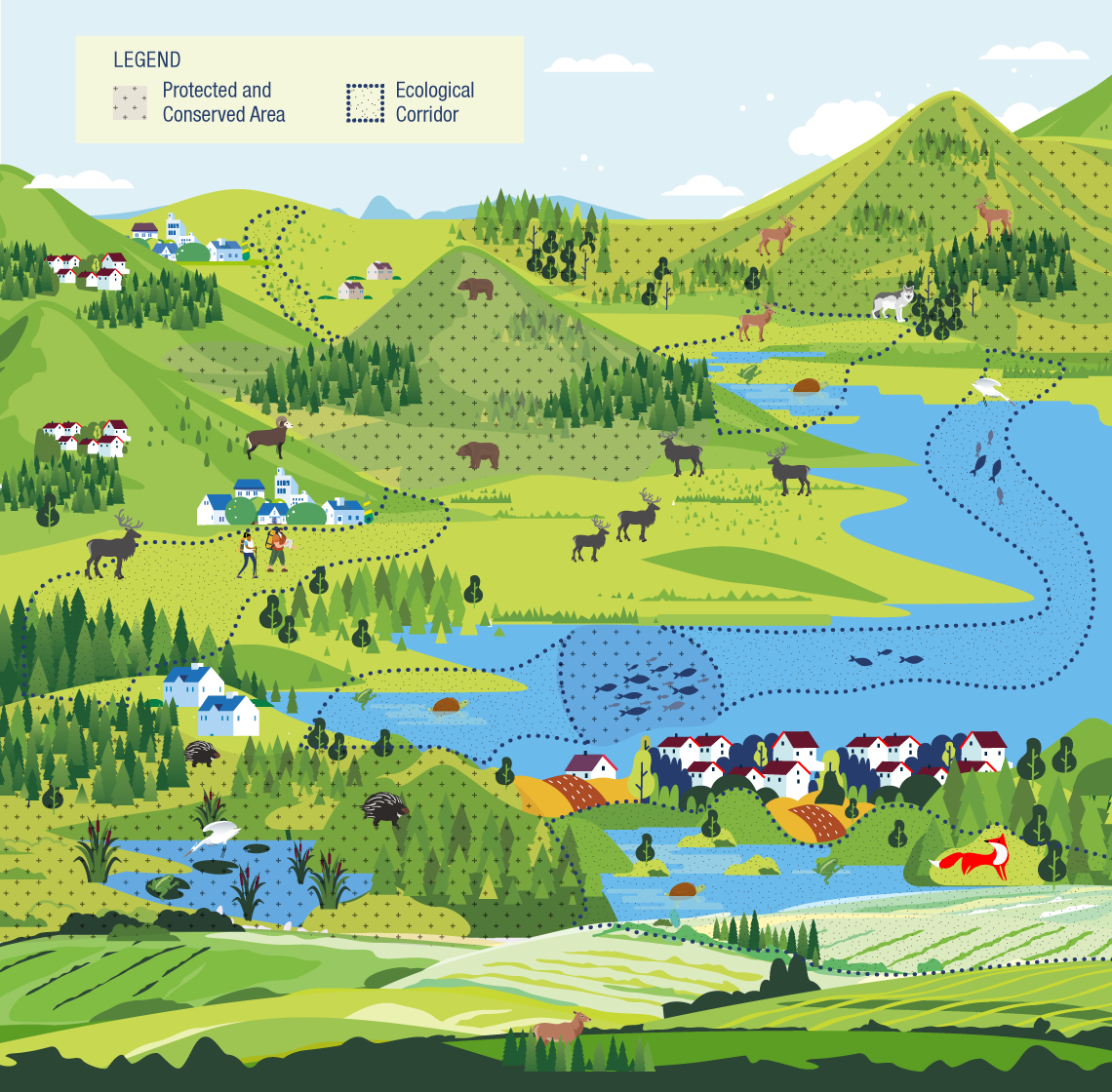

Text version

An ecological network for conservation.

An illustration shows a landscape of mountains, scattered mixed-forest patches, and lakes under a light blue sky. The mountains are in the background, moving to rolling hills in the middle of the image. A large lake stretches across the landscape, with smaller lakes in the foreground. Small towns are dispersed throughout the landscape. A large town and farm fields are visible in the foreground, surrounded by smaller lakes. Patches of forests, mountains, and lakes are shown overlaid with a dotted pattern. These dotted patches of land and water represent protected and conserved areas. Other areas representing ecological corridors are shown outlined by a dotted line. These ecological corridors are connecting the protected and conserved areas.

The corridors stretch between and around the small towns, including some of the farm fields. They cross land and water areas. A school of fish is shown in the area where one protected area and ecological corridor meet in the lake. Many wildlife are also visible throughout the natural areas. Most of the wildlife are shown in the ecological corridors and protected and conserved areas. These include bears, caribou, mountain goats, wolves, herons, porcupines, turtles, deer, and a fox. Two hikers can also be seen using one of the ecological corridors.

Understanding wildlife movement

A first step in better protecting habitats and supporting ecological connectivity is knowing where wildlife travel. For example, Parks Canada wanted to understand the movement patterns and habitat needs of the Woodland Caribou at Gros Morne National Park in Newfoundland. Conservation staff worked with partners to collect and analyze data from caribou tracking collars. From this movement data, it was shown that Main River Waterway area was a main habitat for the caribou. This helped the province create the Main River Waterway Provincial Park—an area located outside of Gros Morne. Recovering caribou in Canada remains a priority for Parks Canada, both inside and outside of park borders.

Transcript

[ This video contains no spoken words ]

[bird sounds chirping in the background].

Two illustrated caribou, one parent and one calf, stand in forested vegetation. An illustrated map of Canada appears in the background, with a place marker over top of Gros Morne National Park in Newfoundland.

A close-up map then shows the boundaries of Gros Morne as well as the boundaries of the Main River Waterway Provincial Park, located about 20 km outside of Gros Morne.

The movement patterns of a caribou over the course of 15 days begins to appear.

First, the caribou track is shown circling the upper reaches of Gros Morne National Park, before moving eastward outside of the park, and eventually into the Main River Waterway.

The caribou then travels inside and outside of the provincially protected park before it returns westward to Gros Morne National Park on day 15.

Movement data for this animation was generously provided by: Natural Resources Canada, the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador, the Department of Fisheries, Forestry and Agriculture

Text transcript

[Tom] Hi, welcome to Gros Morne National Park.My name is Tom Knight.

I'm a biologist here with Parks Canada.

We’ve got a beautiful, calm morning here

in Gros Morne National Park...

…heading into the park to do the caribou habitat work.

So you can see the beautiful landscape

part of Gros Morne National Park in the Lowlands.

We can also see in that landscape

there's some power lines and roads and the community.

And so if you're a caribou, these are all things

that are a part of your landscape.

This project looks at the cumulative impacts

of all of this sort of development,

including climate change

and other things that happen on the landscape,

like forestry and agriculture.

How do those impact

caribou movement through the landscape?

So the Newfoundland Caribou is actually considered

its own kind of unique population genetically

and in their behavior and whatnot.

They are listed as special concern

under the Species at Risk Act,

which means that

they're not near extinction or anything,

but that we should be keeping a close eye on them

and planning for things like future habitat.

You can actually see there's

quite a few tracks, some caribou and moose.

Gros Morne National Park and

all national parks in general,

really provide a core habitat.

In the summertime,

they move into the hills where they have their calves.

But these lowlands are really important,

in winter time especially,

when they come and they can crater down through the snow,

and find nutrition and the vegetation they need to survive the winter.

So a big part of our project

is trying to protect caribou by predicting

where they will potentially cross roads

and show up on highways.

And we can do things like install these signs behind me.

The more motorists are aware of these issues,

the safer that they can be

and the safer it is for the caribou.

We're just getting set up here with all the gear.

We can take a look here and see

what Doug and Rory are up to…

[Doug and Rory] Hello!

[Doug] So what we're trying to do is

get a good understanding of

what type of habitats caribou are using.

So part of that work

is moving on the ground and collecting

information on land cover types.

We're just getting the drone prepped now for our flight.

This camera captures imagery

the same as you'd get from a high-altitude satellite.

This will allow us to characterize

the habitat that the caribou are using.

The camera, which Rory has, captures two types of imagery:

one is regular picture,

but it also captures thermal imagery,

which we hope to use to detect animal locations.

[Tom] So if you passed over a caribou,

then it would actually show up as a thermal image?

[Doug] Yeah, that's what we're testing.

[Tom] All right, so we’ve got Rory ready

to take off with the drone here...

And she's lifting off.

[Rory] You can see the drone flying in a grid pattern

over the study area.

[Tom] Okay. So what are we looking at now, Rory?

That's interesting.

[Rory] So here we're looking down from the drone

and we're seeing the caribou habitat.

There's a nice mosaic of lichen

and different types of mosses.

Lichen is one of their main dietary resources.

[Tom] So that noise we're hearing is that

taking pictures or…

[Rory] That's the shutter, yes.

[Tom] Okay.

[Rory] And you can even see here on the side

there's the caribou paths.

It's rewarding seeing those trails.

It means we're in the right spot.

[Tom] Yeah. Yeah, for sure.

And really, a lot of the theme of this project,

the idea of connectivity and

caribou being able to move through a landscape safely

from one place to another...

So just coming out into the bog here,

while the drone is doing its thing.

Nous allons jeter un œil à certaines des plantes,

Just do a close up look.

The lichens, the white lichens you see there,

they're favorites of caribou during the winter.

And you can see it's a mix of sedges, mosses, lots of beautiful colors.

Sphagnum moss often turns this bright red.

[Rory] It's beeping us and telling us that the drone is.

[Tom] Okay.

[Rory] finished the flight and it's on its way

back to the landing point.

[Tom] So we had a couple of successful flights today.

This is something that's going to actually help map

the caribou habitat across the entire province,

across the whole island of Newfoundland.

Yeah, sure.

So what we'll do with that information

is take it back to the lab and that'll help

paint the picture of what type of habitat

caribou are using in this area.

We do it better together

Parks Canada is collaborating with many partners to support ecological connectivity. We have a long history of partnering with the Nature Conservancy of Canada. We work together to help keep protected and conserved areas connected in priority sites across the country. We make a big difference for ecological connectivity when we pool our knowledge and resources.

We all have unique strengths, expertise, abilities and connections. If we put all of that together, then we can really accelerate conservation.

One way we promote ecological connectivity together is through the conservation of lands in ecological corridors surrounding national parks.

An ecological corridor is a tool used in conservation to connect different protected and conserved areas, often managed by other governments, non-governmental organizations, and private landowners. By studying and protecting ecological corridors:

- the Eastern Wolf and the endangered Wood Turtle have increasingly safer routes to access vital habitat outside of La Mauricie National Park in Quebec

- moose, deer, bears, American Marten, Canada Lynx, and Fishers can now safely reach key habitats beyond Forillon National Park using the Forillon Peninsula Ecological Corridor

We also support landowners in protecting the Waterton Park Front in Alberta. The area provides critical habitat for abundant wildlife beyond Waterton Lakes National Park. Our shared vision and the long-term commitment of local ranchers have helped protect over 100 km2 of this natural gem.

Think big about nature

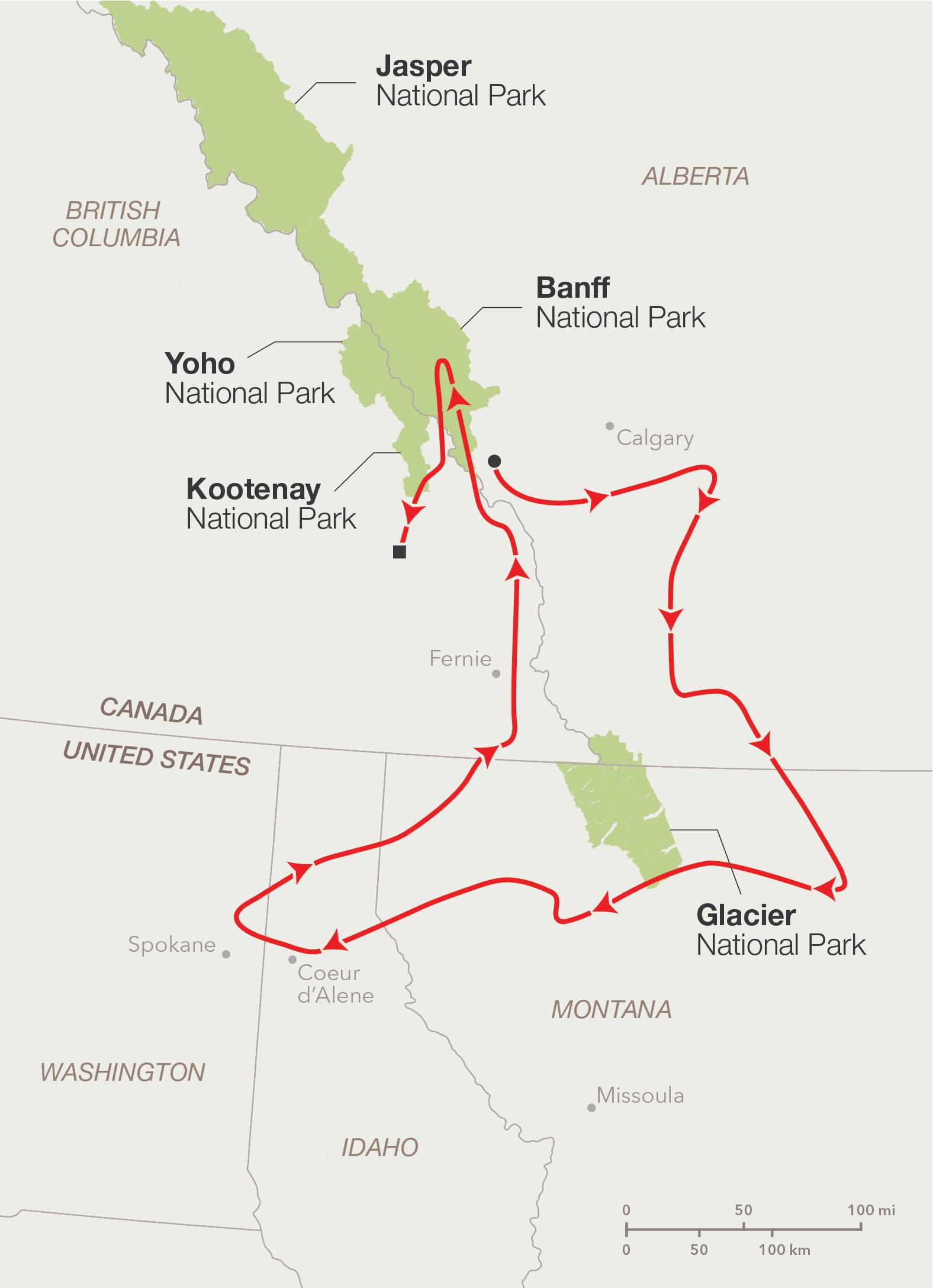

Parks Canada supports ecological corridors, even beyond the borders of Canada! Many animals travel enormous distances to find what they need to survive. In 1991, the journey of Pluie, a radio-collared wolf, showed the scale that we need to consider when working to conserve nature.

Pluie traveled for years between the Canada-U.S. border covering an area of 100,000 km2. That’s 15 times the size of Banff National Park, or 10 times the size of Yellowstone National Park!

Pluie’s great odyssey inspired the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y). This Canada-U.S. joint initiative works to connect a vast network of wild lands and protect source headwaters. Parks Canada manages several national parks in this region. Yet these parks are not big enough to sustain wildlife, like Pluie, long-term.

Large ecological networks, like the one re-established through the Y2Y Conservation Initiative, can help wildlife adapt to climate change. By protecting healthy ecosystems, and by removing barriers for wildlife to access more suitable areas, these networks act as important nature-based solutions to climate change.

-

Text description

This is a map of central U.S. and Canada showing the route of Pluie the wolf.

The route is shown by a red line with arrows to indicate the wolf’s direction. The line begins at a point south of Banff National Park in Alberta. It descends to cross the U.S. border and then loops west through Montana, Idaho and Washington.

Finally, it heads northeast, crossing into Canada again and ending up at a point south of Kootenay National Park in B.C.

-

Text description

The North Saskatchewan River is an important gravel bed river system in the Yellowstone to Yukon region. It starts at glaciers high in the Canadian Rockies, flows east from the continental divide, winds its way through the Prairies, and drains into Hudson Bay. Gravel-bed river ecosystems and floodplains are vital habitats in North America. Animals like deer, elk, caribou, wolves, and grizzly bears rely on these floodplains for food, habitat, and migration paths. These rivers also connect landscapes for both land and water species—crucial amid climate change.

-

Text description

Representatives from Glacier National Park in the United States and Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada renewed their transboundary relationship to co-manage this unique protected area. These two parks are a model of international cooperation. Designated as the world's first International Peace Park in 1932, it was a symbol of the long-standing friendship between Canada and the United States. The importance of these parks as shared natural treasures was recognized.

Y2Y is helping the last intact mountain region of this scale left in the world stay natural and healthy. By sustaining a vibrant network of protected areas and corridors, Y2Y can serve as a global model for how we need to do nature conservation.

Restoring cultural connections

It’s not only the natural environment that gets affected when ecological connectivity is lost. For thousands of years, the Mi’kmaw people have been using the Mersey and Bear River watersheds in the Kespukwitk region of Mi’kma’ki (in Nova Scotia) for travel, hunting, and to live. These two watersheds formed an important travel route between the Atlantic Ocean and Bay of Fundy. It is also a biodiversity hotspot, with many species at risk and species that hold cultural importance.

Over time, lumbering dams and power dams were constructed on the lower Mersey River, resulting in the interruption of fish passage and flooding of large areas. This significantly changed the area’s natural ecological and cultural connectivity. Local Mi’kmaw people lost important fishing and hunting grounds. Many important cultural sites (e.g., gathering areas, burial grounds, portage routes, and eel weirs), were also lost with flooding.

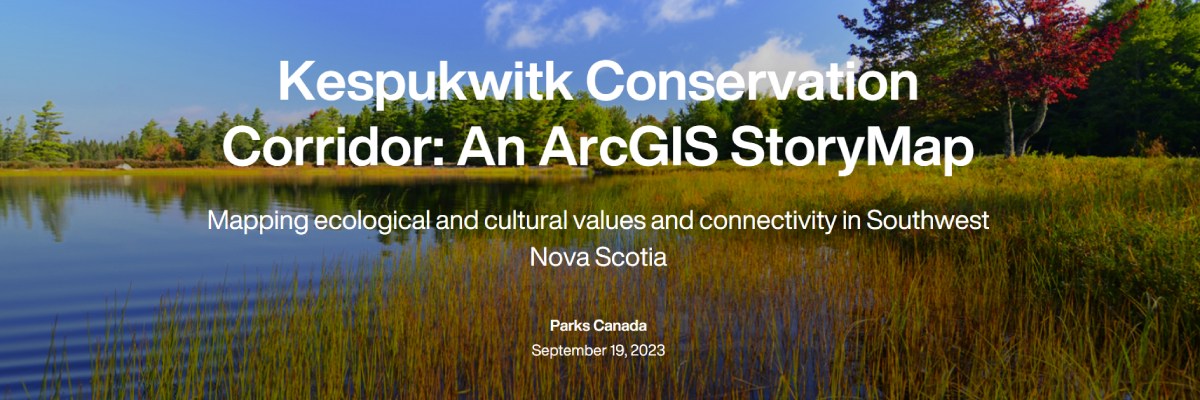

Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site is in the heart of the Kespukwitk Conservation Corridor and the Kespukwitk Priority Place—an Environment and Climate Change Canada priority place that aims to conserve Species at Risk in Southwest Nova Scotia.

Parks Canada worked with local Indigenous communities (Acadia First Nation and Bear River First Nation) and the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq using a two-eyed seeing approach—braiding Indigenous knowledge with western science—to create a Story Map that highlights key areas for protection in the Kespukwitk Conservation Corridor.

The aim is to identify key areas in the Kespukwitk Conservation Corridor that can be protected to improve ecological connectivity across lands and waters, and restore cultural connections for the Mi’kmaw people.

Making roads safer for wildlife

Roads and railways move vital supplies, and connect us with family, friends and treasured places. Yet roads are the biggest source of human-caused wildlife death in Canada’s national parks. They also obstruct ecological connectivity.

That’s why for 40 years, Parks Canada has been working to reconnect habitats and help save the lives of wildlife. With help from partners, our built asset teams design and construct wildlife overpasses, underpasses and eco-passages that help keep wildlife—and people—safe.

We also support partners in building wildlife crossings to restore connectivity. In September 2023, Parks Canada and the Y2Y Conservation Initiative co-hosted a group of delegates from the United States and Canada. They came to Banff National Park to share knowledge and to learn from decades of experience that we’ve gained in making roads safer for wildlife.

Banff is a learning lab for improving terrestrial and aquatic connectivity through infrastructure. We’ve been doing this for so long and have tried many different things.

-

Text description

In August 2023, the Government of Canada announced a contribution of over $1.9M to support ecological connectivity in southeastern British Columbia and southwestern Alberta. Funding from Parks Canada’s National Program for Ecological Corridors will minimize the impact of Highway 3 on wildlife in the area by decreasing collisions and connecting habitat fragmented by the highway. This project plays a key role in connecting wildlife populations east-west over the Rocky Mountains and north-south across the Canada-U.S. border and between the large, protected areas of Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park and Banff National Park.

Habitat stepping stones

Wildlife on land aren’t the only ones that rely on habitat connectivity. Every spring and summer, a relay of Monarch Butterflies migrate from Mexico to Canada. The meadow around the ruins of Fort St. Joseph National Historic Site in Ontario provides a place for the endangered Monarchs to rest and feed on native wildflowers, like Common Milkweed. In the fall, these butterflies give birth to a special cohort of Monarchs. This longer-living generation of Monarch Butterflies then migrates over 3,000 km to Mexico to start the process again. Conservation staff are working to protect the meadow at Fort St. Joseph—an important habitat stepping stone along this epic journey.

Go with the flow

Like on land, maintaining connections in aquatic ecosystems is also important. In 1941, the Minnewanka Dam was built on the Cascade River in Alberta. When the river’s once mighty flow dwindled into a trickling creek, endangered Bull Trout and Westslope Cutthroat Trout also disappeared.

Staff at Banff National Park and partners began restoring Cascade Creek in 2010. By repairing 9 km of stream habitat, they restored natural flow and downstream connectivity. Cascade Creek is set to become a refuge for native Bull Trout and Westslope Cutthroat Trout.

Clear the way

Getting rid of clutter can be a therapeutic cleanse. It can also help wildlife recover, if that stuff is obstructing healthy habitat. That is the case for the Greater Sage-Grouse at Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan. This endangered bird is threatened by structures like overhead power lines and fences. They offer convenient perch sites for owls and hawks who prey on the grouse. Fences can also be a direct source of mortality for the grouse, who sometimes fly into them.

To help, Parks Canada partnered with SaskPower to remove above-ground service poles and bury almost 13 km of power lines. Conservation staff removed over 75 km of fences and marked over 174 km of fencing to make it more visible to the birds. Thanks to this work, threats from predators and collisions have been reduced.

Conservation staff also tidied the tundra at Qausuittuq National Park in Nunavut. Caribou are a vital source of food, clothing, and tools for local Inuit. Yet oil and gas exploration in the 1970s and 1980s left Bathurst Island with a legacy of industrial waste. When the park was formed, Parks Canada and local Inuit noted something important—the waste was obstructing the natural habitat of the endangered Peary Caribou. After many years of cleanup, the land was healed and became more usable for the caribou and local Inuit. This work contributed to the survival of caribou relied upon by local Inuit.

Stay connected

Ecological connectivity is key for a healthy planet! Wildlife thrive when they can safely access habitats and neighbouring populations. Natural processes, like the movement of water, need clear paths to flow. The well-being of Canadians depends on a healthy and diverse environment. It’s no wonder that ecological connectivity is a global priority for the health of our planet!

So how can you help keep wildlife connected?

- Plant native pollinator gardens, like common milkweed, to provide habitat stepping stones for Monarch butterflies

- If safe to do so, keep parts of your property natural and accept that some wildlife need to move through your property

- Create natural buffers along streams, lakes and fields for wildlife to use

- Support the conservation of lands and waters that give wildlife more room to move

- Watch for wildlife crossing roads in natural areas and, where safe to do so, help species in need cross the roads (turtles should always be moved to the side of the road they were moving towards)

Nature in your inbox

Get our latest nature and science stories, travel tips, and more.

- Date modified :